Just over 80% of all Indiana third graders passed the 2021 spring reading assessment, according to state data released Friday. But achievement rates were far from equal across student groups.

Results of the Indiana Reading Evaluation and Determination assessment show the unequal effects of the pandemic on Black and Hispanic students, as well as a widening gap between children who come from economically impoverished backgrounds and those who don’t.

The gap in passing rates on state tests between white and Black students grew to 25.5 percentage points last spring from 2019.

The data is in line with other information previously released by the state, like attendance rates which showed that students had unequal access to in-person learning during the 2020-21 school year.

ILEARN scores also showed that just over one quarter of students in grades 3 through 8 scored proficient in both English and math.

The state’s overall IREAD pass rate fell six percentage points from 87.3% in 2019 to 81.3%, but scores among Black third graders dropped by double that rate — the greatest decrease among student groups.

Around six in 10 of Black students passed the test, compared with 9 in 10 white students.

The gap in passing rates between students who receive subsidized lunch and those who don’t also widened by five percentage points from 12.3% in 2019 to 17.4% last spring.

No demographic groups improved their scores from the spring tests from two years ago.

That the pandemic hurt scores is not surprising, said Cristina Santamaría Graff, interim assistant dean of student support and diversity at Indiana University Purdue University in Indianapolis.

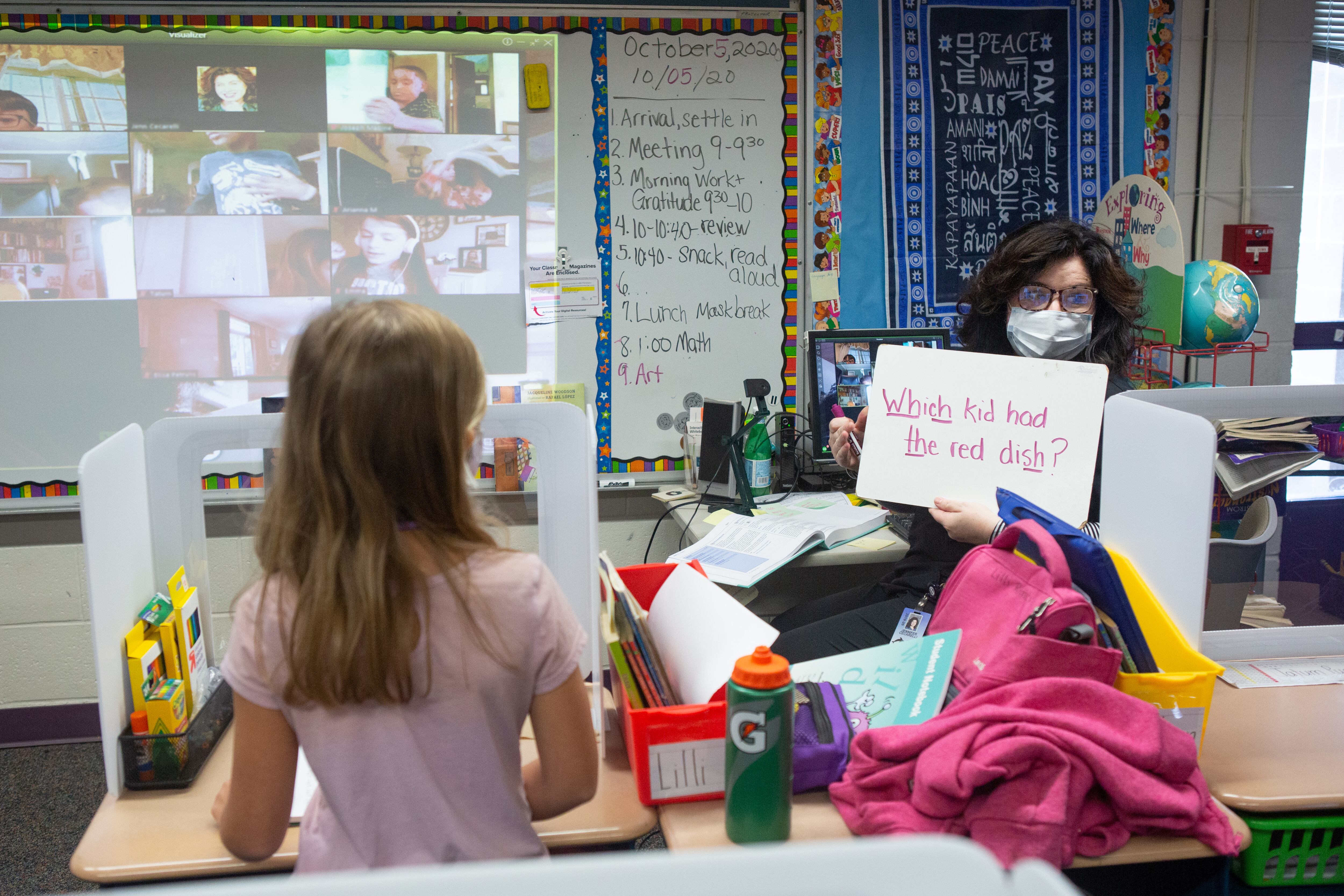

The pandemic and efforts to control it caused schools to toggle between in-person and virtual learning; raised issues with access to resources, transportation, and communication devices; prompted many experienced teachers to leave; and posed severe challenges to students and families.

Given that, putting a lot of weight on test scores is problematic, Santamaría Graff said.

“Reading scores are one little lens to look at this massive issue of a lot of systems breaking down all at once,” she said. “And things that weren’t working before the pandemic are really falling apart.”

According to the state data, students in special education had the lowest IREAD pass rate in both 2019 and 2021, at 60.9% and 52.4%, respectively.

But individual experiences with learning during the pandemic varied widely, said Santamaría Graff, an associate professor of special education and urban teacher education whose expertise includes bilingual and multicultural special education.

Some families of students with autism reported that academics improved in a home environment, where they had more control over stimuli and sensory challenges. Meanwhile, students with Down Syndrome faced barriers to receiving consistent and quality virtual instruction, Santamaría Graff said, and saw corresponding declines in academic performance.

As a group, English learners seemed to have slipped the least from 2019 to 2021, by just 1.2 percentage points.

Santamaría Graff noted that that data point required further investigation into, for example, what portion of English learners took state tests, whether they felt comfortable sitting for in-person assessments, and even whether immigrant families moved out of the state.

Looking to the new school year, Santamaría Graff said educators report feeling stretched thin, and may not have the bandwidth to provide students with all the support they need to catch up.

But school districts and the state should involve families in decisions about how best to help students learn.

“It’s important to take a holistic view of the needs rather than pinpointing that students are doing poorly in reading and dedicating resources only to improving reading scores,” she said.