Each month, a small team at St. Monica Catholic School gathers to compare notes on the school’s 390 students. The staff members talk not only about which students are struggling in class but also about which are visiting the nurse — and what patterns might emerge.

The 1½ -hour meeting is a simple strategy. Including the school nurse on the academic tracking team pays real dividends, Principal Eric Schommer said. Nothing falls through the cracks.

A nurse, for example, may notice that a student consistently visits with a stomachache during math class. Talk to the student, and it may turn out the problem is actually with understanding math, and the school should address it with tutoring or homework help.

“Sometimes the grades don’t demonstrate that the student is struggling,” Schommer added.

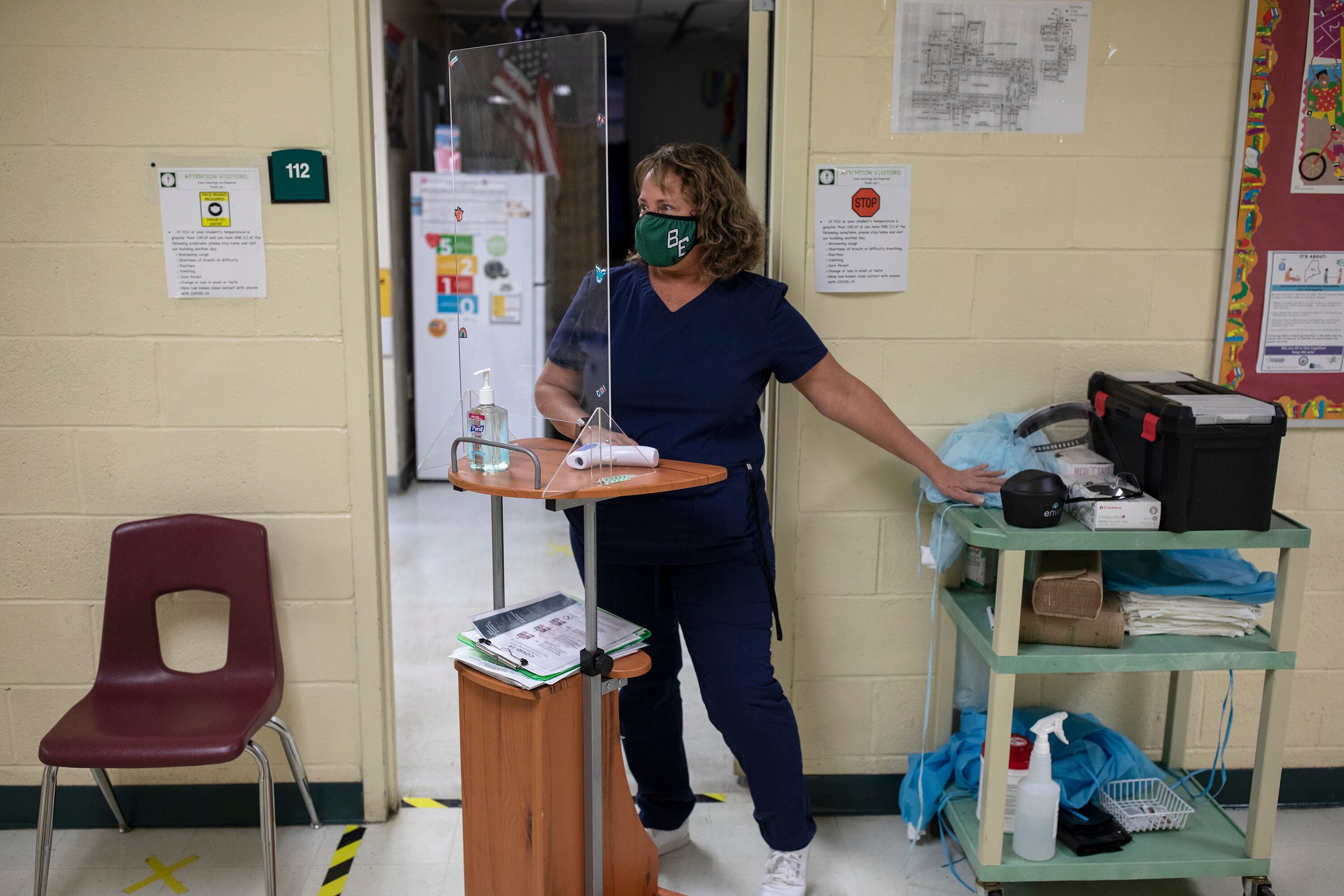

School nurses are getting renewed attention and heavier workloads during the coronavirus pandemic. But they also can play a crucial role in supporting students academically, by providing health care that improves children’s ability to learn and by collecting data to help identify students who are likely to fall behind.

It’s a valuable moment for schools to think about providing student health care, advocates say. Students are grappling with the trauma of the coronavirus. And schools have a rare opportunity to invest in health services because of the surge of federal funding they are receiving.

Last year, St. Monica started working with the Paramount Health Data Project, which is trying to bring a similar approach to more Indiana schools. The Indianapolis nonprofit is currently partnering with eight schools to increase the role of nurses in academics by helping them collect and analyze data on student health.

When students visit, the nurse collects information on the health concern that brought them to the office. The data project then combines that information with student test scores to come up with reports that help each school anticipate possible lower academic achievement based on health data, said Addie Angelov, executive director of the project.

“This is a unique piece of data that would give Indiana schools an edge in making up those learning losses that we know everyone is navigating,” Angelov said.

Because the approach ties health care to academic results, schools that are using the program can pay for nurses by tapping federal funding for educating students in poverty, Angelov said.

The idea for the project began about seven years ago at the Paramount School of Excellence, an Indianapolis charter network that has been piloting the program.

Through a partnership with a local hospital, Paramount leader Tommy Reddicks reaped a trove of health data on students. When he combined that data with the school’s academic reports, he saw that certain health problems that are common among children in poverty, such as persistent headaches or skin conditions, correlated with lower academic performance, he said.

That suggested conditions in a student’s home, such as poor air quality or mold, could affect academics, Reddicks said.

Now Paramount works with Angelov and the data project to produce reports on student health and academic outcomes at the network’s three schools. By using nurse visits, the schools identify hundreds of students each year for academic help, Reddicks said.

One benefit of the approach is that it is fast. Because Paramount typically looks at test results over time to identify students who need support, it can take several months to catch problems. With health data, the school can spot students who might need help sooner.

The schools might be sweeping in some students who would have been fine academically, Reddicks acknowledged, but because the interventions are a relatively light lift, he doesn’t think they have a downside.

Now Reddicks is pitching the strategy to other educators.

“We need to tell principals, not only is this the best thing for kids, but this will raise test scores,” Reddicks said. “This will help you change your culture. This involves another active member in your academic team.”

It’s hard to get a clear picture of the number of nurses in Indiana schools. More than 400 Indiana districts and charter schools reported employing 1,165 nurses last school year. That data might miss some: The state doesn’t always include schools that contract with hospitals or health networks to hire and train their nurses.

The appropriate number of students per nurse also depends on the specific needs of each school. Although it’s a relatively small school, St. Monica has had a full-time nurse for at least a decade. It’s a crucial service because many of their students come from low-income or immigrant families and lack access to regular medical care, Schommer said.

Improving health care for children has long-term benefits, said Claire Fiddian-Green, the president and CEO of the Richard M. Fairbanks Foundation, an Indianapolis philanthropy that funds health and education initiatives. (The Fairbanks Foundation also supports Chalkbeat. Learn more about our funding here.)

“There’s a lot of data to show that education and health are intrinsically linked,” Fiddian-Green said. “Health affects the ability to succeed in school. And then, in turn, education outcomes affect future health outcomes.”