With three weeks to go before she was set to star in the school musical last fall, Alexa Margolius watched as dozens of students were pulled out of school after one friend caught the coronavirus.

She fervently hoped she wouldn’t be quarantined — or, worse, get sick. The cast of “Bright Star” hadn’t yet rehearsed the entire show, and she had 11 solos and 12 costume changes to practice. It was supposed to be the highlight of her senior year at Avon High School.

Alexa made it almost through the end of the week before the assistant principal came looking for her. She had been exposed, too. When her mom picked her up to start her quarantine, Alexa sat in the car and sobbed.

In the suburbs of Indianapolis, the Avon district is trying to have as normal a year as possible in the midst of a pandemic — but it comes with the challenge of students and teachers spending weeks, sometimes adding up to months, out of school for quarantines as a cautionary measure to prevent the spread of the virus.

Since throwing its doors back open in late July for full-time in-person learning, complete with extracurriculars, the Avon district has reported more than 600 cases of COVID-19 among the roughly 10,000 students and staff who returned. Thousands of students and staff have been ordered home to isolate, peaking at more than 850 people quarantined one week in January.

“That’s been the part that has been the most exhausting,” said Avon Superintendent Scott Wyndham, “is the constant rotation of quarantines, and how to help students stay up with their coursework so that they’re not behind when they come back.”

This was a consequence of coming back five days a week in person. But it was a risk Wyndham and the school board were willing to take, with the blessing of the local health department, so students could learn in person and participate in the sports and activities that are often what students love the most about school. And 89% of district students have returned.

Unlike so many students across the country — some of whom still haven’t returned to classrooms — Avon High School students have been allowed to play football games, perform in band concerts, and wrestle in state championships. The chess club, the calligraphy club, and the history club all meet in person. Students have raised money to throw a pie in their favorite teacher’s face, done crafts in the library, and dropped eggs off the second-floor balcony for physics class.

While students say they’re thankful to be back, they’re also on edge. They describe the year as messy, chaotic, and uncertain, wondering every day whether they’ll have school and activities taken away from them.

“We just don’t want to get our hopes up,” Alexa said, “to just get disappointed.”

After being the first Indiana district to close one year ago when a student became the state’s third reported coronavirus case, Avon schools reopened in July with mask requirements, cleaning supplies, and distancing where possible.

Other schools in Indianapolis took a more cautious approach. But at Avon High School, home to about 3,000 students, masked teenagers flooded down the hallways and ate lunch in assigned, spaced-out seats in the cafeteria.

Within the first few days, the school had positive COVID-19 cases — and its first quarantines.

Sophomore Noah Jakresky doesn’t know who exposed him to the coronavirus in those first few days or where it happened. All he knows is he fell within the six-foot circle of where that person sat.

It was the first of four times he’d be quarantined so far this year.

“It sucked,” 15-year-old Noah said emphatically.

For two weeks, his routine at home went like this: “Wake up, get your laptop, see if your assignments are there, and if they aren’t, then you’re screwed.”

He had wanted to return to school in person for two reasons: to run track and to stay focused. But Noah’s first-semester quarantines added up to more than a month out of the classroom, and he often came back to mountains of make-up work. His grades yo-yoed as his missing assignments were marked as zeroes until he turned them in.

He ended up failing Drawing I, “one of the easiest basic classes,” because he said his teacher didn’t accept all of his late work.

Holding a quarantine-free streak has been cause for excitement. Noah hasn’t caught the virus, but he worries when he sees other athletes sidelined with lingering side effects.

He looks forward all day to track practice, though his coaches make the whole team do push-ups when someone shows up without a mask. He has grown tired of arguing with students who don’t want to wear masks, or trying to say “mask up!” with a lighthearted tone or an eye roll.

“I just give up at this point,” Noah said.

During her quarantine, Alexa Margolius still played the lead in the musical in rehearsals — by Zoom.

A laptop with Alexa and other quarantined cast members on screen sat atop a cart that was rolled around on stage, so the students at school could dance, sing, and talk to them.

Sometimes, as they rehearsed the musical set in the 1920s and 1940s, they forgot about Alexa, leaving her sitting in her kitchen wondering what was going on. Or the lag in the video chat led to awkward pauses and missed timing.

But quarantine afforded Alexa time to catch up on her sleep, and “in the end,” she said, “it was probably best, because if I was at home, I had no chance of getting COVID.”

When she finished the requisite quarantine without developing symptoms, Alexa returned to school with just a week until showtime. She asked her teachers if she could sit far away from everybody else to minimize her risk.

As the opening of the musical approached in mid-November, Alexa’s anxieties climbed alongside Indiana’s coronavirus outbreak, which rose to an average of about 6,000 new cases each day. A cast member was sent home and replaced with an understudy.

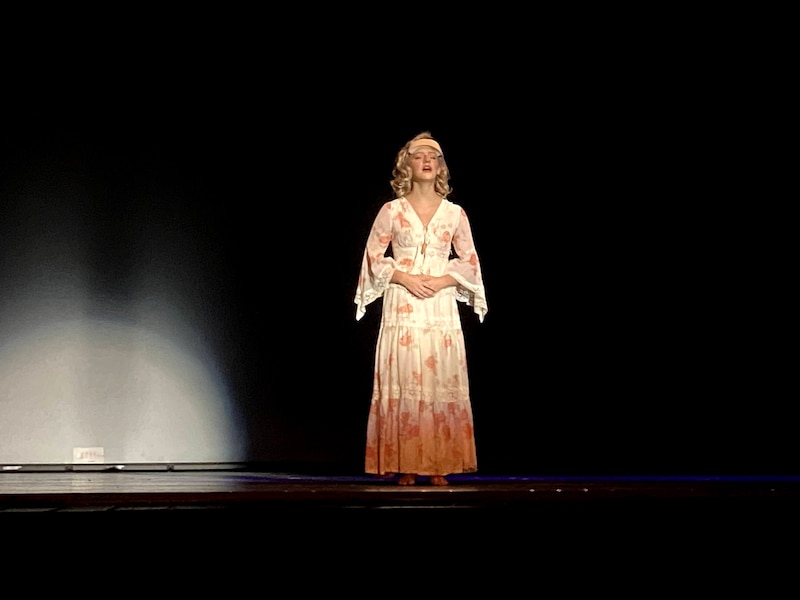

But despite her fears, the worsening pandemic didn’t cancel the show. The stage lights came up on Alexa behind a plastic face shield, her reflection and voice bouncing back at her as she appeared in front of an audience limited to a fraction of the usual size.

Avon High School’s production of “Bright Star” had to be slightly modified for the global pandemic. The love story lost its kissing scenes, with the teenage couple only allowed to get close enough to dance together or embrace briefly.

Alexa poured her emotions, including her stress, into her role for her last senior performance. Backstage between scenes, she wiped the tears off her face shield with tissues.

“It made me believe in myself a lot more, knowing that I can do that for my future and work under pressure,” she said.

The week after the musical, cases at school ticked up quickly.

Senior Sriya Koganti had been cautious all year. She came back to take a full load of AP courses — six in the fall, five in the spring — but found being around so many other students rather nerve-wracking, especially in the beginning.

Instead of eating lunch in the cafeteria, the only time during the seven-hour school day when she took off her mask, Sriya ate in a classroom with a teacher and one other student.

The speech team, which she has led for three years, competed virtually. Sriya gave her speeches in an empty room to a computer screen. Sometimes, she never even saw the judges when they left their cameras off.

Despite these precautions, she learned in November that she sat next to a friend whose parent had tested positive for COVID-19. They shared a two-person table with no divider between them, distanced from other classmates but not each other.

Sriya decided to quarantine herself.

A few days into Sriya’s voluntary isolation, Avon High School shut down its classrooms and turned to remote learning amid the rising cases. With about 750 people quarantined across the district, school officials said they didn’t have enough teachers to run in-person classes.

Avon High School saw some of its highest case counts while closed for e-learning, which would only be matched by the first few weeks after winter break.

Through contact tracing, administrators said they believed the virus was spreading through sports, sleepovers, and gatherings outside of school — not from the classroom setting. They took that as a sign that high school students are safer in school than out of school.

“They’re washing their hands, they’ve got access to lots of hand sanitizer,” said Wyndham, the superintendent. “We are providing seven hours a day for kids to be masked and protected.”

During her time at home, Sriya competed in a virtual national speech tournament, sending in a 10-minute video that won first place for original oratory. In it, she took on the topic of toxic positivity, criticizing remarks about the pandemic such as, “I don’t live in fear,” “This thing will pass,” and, “You’ll be fine.”

Those comments, Sriya told the camera, plant “false narratives, false hopes, and diminishing empathy.”

Instead, she called for compassion and support.

“Simply put,” Sriya said, “It’s OK to not be OK.”

Students returned from winter break to a spike in cases at the start of the second semester.

Star wrestler Ke’Shawn Dickens wasn’t really worried about catching the coronavirus — “sometimes,” he said, “I forget that it’s even a thing” — but the pandemic was upsetting his senior year.

The year was crawling by, and Ke’Shawn found himself “constantly on edge at all times,” he said, wondering “if school was going to shut down, if my season was going to end, if I was going to lose my next match.”

In February, Ke’Shawn got his final shot at wrestling. He had missed three competitions during a double quarantine — his exposures overlapped for a three-week quarantine — and had to work to keep his weight down without practices.

Ranked ninth in the state, he made it to the state finals at Bankers Life Fieldhouse, the NBA arena downtown.

Ke’Shawn wanted to treat it like any other match. But he missed the fierceness of what’s typically a packed arena, muted by capacity limits.

He went for it — a little too hard, though, and lost in overtime.

“I think I had a really good season,” Ke’Shawn said. But was it the senior year he imagined? “Nowhere close to it.”

Despite their weariness of quarantines, none of these students or others who spoke to Chalkbeat are particularly interested in re-litigating whether Avon made the right decision to open back up.

“This is our new normal,” said junior Faith Kipkulei.

In recent weeks, quarantines have started to lighten, lifted by falling cases statewide and loosened state health rules. In certain instances, schools can now reduce the distance for determining close contacts and the length of quarantines.

Wyndham, the Avon superintendent, said he hopes the state will continue to roll back requirements.

“We’re sending home thousands of perfectly healthy kids for days, and they never develop symptoms. They never test positive. They just miss a lot of instruction,” he said.

At the high school, teachers are exhausted, juggling quarantined students with their regular classrooms, and sometimes also handling virtual or credit recovery classes. Before Indiana teachers became eligible for the vaccine last week, some added volunteer shifts to their days through the local hospital in order to qualify for a shot.

With three months left in the school year, the pandemic burnout is getting to the students, too. Some say the lack of motivation is compounding senioritis. Prom plans are still being finalized. Graduation seems like it will feel as much of a relief as an accomplishment.

As senior Skylar Jakresky puts it: “I’m not happy. But I am glad to be in person.”

If you are having trouble viewing this form on mobile, go here.