Indianapolis Public Schools’ percentage of employee applicants of color has declined, according to a recent audit of recruitment and retention presented to the school board.

As a part of the antiracism policy that the district adopted in June, officials are analyzing not only what students are experiencing and learning in schools, but also how the district hires and treats the people who lead those students every day.

“What we are doing now is lifting these words off the page and putting them into action,” said Patricia Payne, the district’s director of racial equity.

According to its policy, the district aims to increase the diversity of job applicants through partnerships and programs and to boost retention by ensuring staff feel supported and included.

The audit, which was conducted earlier this school year, revealed that the district still has a lot of work to do.

The audit looked into how the district treats racially diverse applicants, new hires, and employees seeking promotions. It revealed that the district had fewer staff of color at schools compared with certain other school districts and that staff of color were not likely to recommend others to apply to the district.

The audit also found that staff felt the onboarding process lacked clarity around job responsibilities and that the district didn’t clearly outline paths for career advancement. The latter, in particular, led to “confusion and frustration,” respondents of color said.

IPS employs more than 5,000 people, according to its website. Staff of color make up 43% of district leaders, 26% of teachers, and 65% of support staff, according to the district.

During their March 25 meeting, school board members said they wanted the race and equity work to be more consistent and proceed quickly. Shonterrio Harris, the district’s manager of equity advancement, said IPS is putting some of the recommendations in place and will prioritize others in coming school years.

The audit recommended changing online platforms to better track staff of color, holding targeted events to find candidates of color, and mentoring for new hires. The district adopted a new online tracking system of candidates in February.

Board member Diane Arnold sought specifics about putting plans in place, saying, “It’s important that we stay on top of this.”

Superintendent Aleesia Johnson said she and her team would provide quarterly reports to the board.

Board member Will Pritchard called the efforts critical to the district.

“I would like to see some things quicker,” Pritchard said. “I would love to see some parts of it put into place by the next school year.”

The audit also highlighted some district successes: having a significant number of Black leaders, including half the executive team and Johnson, the first Black woman to hold the title.

The district also has mandated racial equity training for all staff.

Auditors reviewed more than 50 documents, conducted focus groups, and looked at surveys of 2,180 respondents.

The audit findings come at a time when many school districts across the nation are wrestling with how to be anti-racist from their staffing decisions to their curriculum, especially after a summer of police brutality and calls for racial justice.

IPS is not alone in the struggle to hire and retain staff of color. School districts in Indianapolis, throughout the state, and nationwide also have labored over trying to recruit teachers and other staff of color.

State data shows that in IPS, 40% of students are Black, 32% are Hispanic, and 22% are white. But the percentages of teachers of color among IPS’ nearly 2,400 educators are disproportionate: 73% of teachers are white, 21% are Black, and 3% are Hispanic.

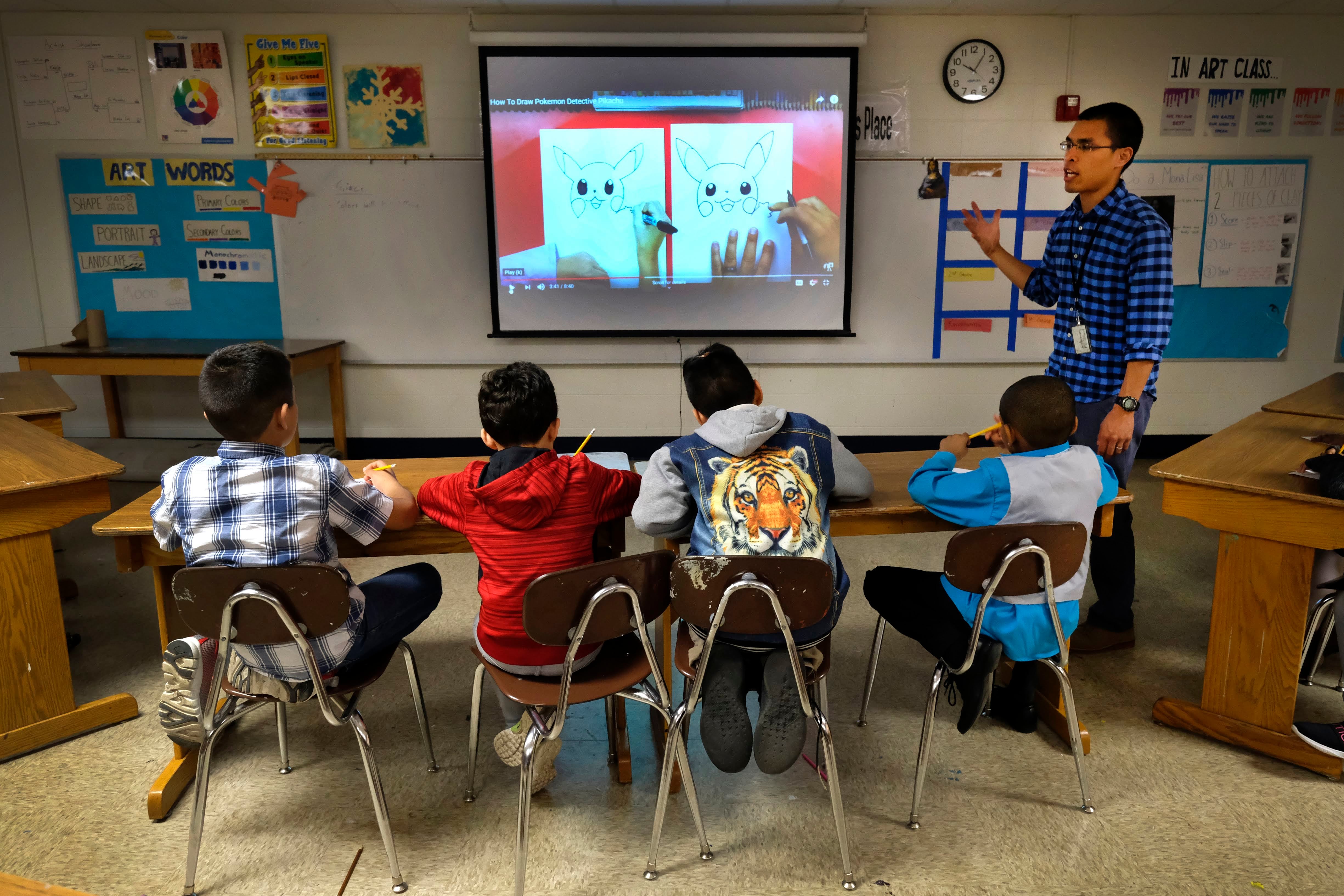

Matthew Jackson, a 10-year veteran IPS fine arts teacher, has seen the effects of not having a proportionate number of Black teachers in schools.

“It’s definitely become like a big sore thumb when it comes to looking at my Black students and seeing that I may be the only Black teacher on their schedule,” said Jackson, who teaches at Crispus Attucks High School.

He applauds IPS for its mandatory racial equity training, but he questions what the district is doing to attract and retain Black teachers. He thinks the district struggles with giving staff members a voice and including them in decision-making.

“Even with COVID-19 crisis, we haven’t been given any options to voice our opinions for our safety or how we feel. We’re just told what to do,” Jackson said. “I think a lot of problems that occur could be avoided if we had a voice before big decisions were made.”