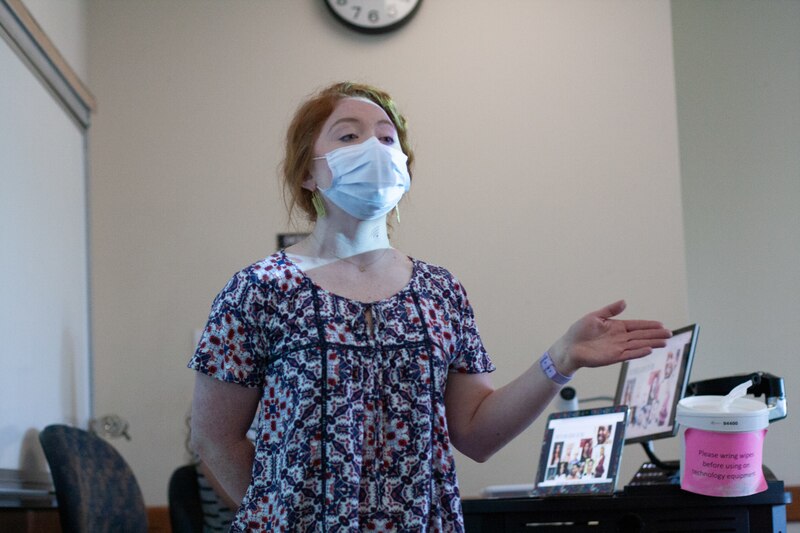

“Have you ever felt out of control at school?” counseling intern Chloe Wilkerson asked a classroom full of restless fifth graders in Indianapolis last week.

Five students slowly raised their hands.

“Everyone has,” Wilkerson said, encouraging the rest of the dozen students to join in as she held her own hand up.

She advanced to the next slide in her presentation, a cartoon about the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. The brain reacts to stress and anger, she explained — and through techniques like coping mechanisms, you can control how you respond.

Wilkerson was leading one of the group counseling sessions provided weekly at Horizons at St. Richard’s Episcopal School, a summer program for students from low-income backgrounds that teaches breathing exercises and yoga along with math and reading. Families pay $25 for each prekindergarten through eighth grade student to attend for 5½ weeks.

Horizons aims to address disparities in learning for low-income students, mixing academics with fun activities like swimming and trips to the Children’s Museum. Horizons’ counselors also help students learn more effectively by addressing behavioral problems and encouraging social and emotional development for its 150 students, many of whom have experienced high levels of trauma.

After more than a year of school upended by the pandemic, program leaders say the counseling program is even more important this summer.

Horizons counseling supervisor Jen Money-Brady said during the pandemic, she saw many students deploy coping skills they had learned previously at Horizons, such as recognizing when they need a break rather than getting angry.

But the pandemic so devastated low-income communities and families of color, who faced higher rates of job loss, food insecurity, sickness, and death, that small coping mechanisms can’t solve all the fallout for children. Money-Brady is concerned about the long-term effects of collective pandemic trauma on students.

“It’s not normal to lose this many people close to us, or to have so many people be sick and be worried about that,” Money-Brady said. “When I talk with students, there’s almost a numbness with knowing that someone has COVID and so many deaths that have come from it.”

Yoshida Williams-Bolds, who leads counseling for Horizons middle schoolers, said she’s concerned about COVID’s impact on students’ mental health. She said the prolonged period without the structure of school prevented many students from socializing and dealing with rules, both experiences important for their development.

While it’s difficult to determine how the pandemic affected each student, Williams-Bolds said behavior has worsened across the board. Many students had trouble adjusting to the structure of Horizons during the first week of camp, talking over teachers, running in the halls, and getting tired early in the day.

“I know that’s definitely the aftermath,” she said. “Yesterday I had a couple of students that were caught running, and I had to intervene and discipline.”

Horizons teachers and counselors often turn to small-group instruction to tackle misbehavior. Last week, one teacher struggled to capture the attention of five students, as they poked an electrical socket and laid their heads on the table rather than reading the next chapter of their books.

Williams-Bolds said in the first week, she and other counselors observed students and flagged those who would need additional one-on-one attention from teachers and counselors. As the program continues, she hopes to build a rapport with students who initially resented her for disciplining them.

In addition to addressing behavioral problems, counselors at Horizons this summer will focus on helping students deal with the emotional fallout from months of isolation, touching on topics like friendship, anger management, and loneliness. The counseling will come in multiple forms, sometimes in a class lecture, other times in small-group settings.

As part of her learning plan, one student took a break from class to sit in an armchair in the hallway, reading “James and the Giant Peach” with a counseling intern. The student has one-on-one time built into her personal schedule to allow her to build a relationship with counselors and focus without the distraction of classmates.

Anye Watson, a 14-year-old with heart-shaped sunglasses and armfuls of bracelets, has attended the Horizons program since first grade. In that time, she has learned math, reading, swimming, yoga, breathing exercises, and the mindset that it’s OK to have struggles — “you know, everybody has problems,” she said. She plans to return next summer as a Horizons intern, assisting teachers and helping students learn to swim.

Anye said she often uses coping techniques she learned at Horizons, including breathing exercises, yoga, and standing during class if she feels sleepy. She said she’s glad the program teaches coping mechanisms to every student.

“You never know what’s going on in somebody’s life,” Anye said. “Teaching them those coping mechanisms, without actually even knowing what they’re going through, that helps them.”