Damon and Brandi TaZiyah’s three children have an ideal vision of what diversity looks like in the classroom.

It’s a variety of races throughout the entire school, says 9th grader Ali.

Or, classmates are sharing their lives and learning from each other, said 7th grader Sanai.

“And being equal skin colors,” 2nd grader Laila said.

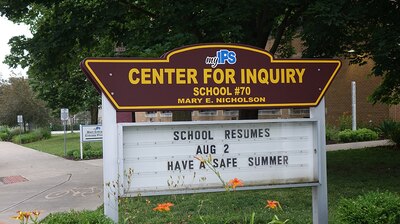

But the family said that is not the reality at Center for Inquiry School 70, a choice school intended for any Indianapolis Public Schools student who wants to attend and designed to promote high academic achievement, a global perspective and cultural diversity.

In the five years since CFI 70 opened in the affluent and majority white Meridian-Kessler neighborhood, the number of students on paid meal plans increased, indicating that the wealth of the families at the school grew, and the white student population increased from less than half of the school to 60% in the just completed school year.

The school has even become a top selling point for $375,000 homes located within a half-mile radius, known as the proximity priority, as families living there would be favored to win a seat in the district’s lottery enrollment.

Now, parents at the A-rated school are pressuring IPS officials to change enrollment policies that they say favor neighborhood families over the more diverse district population. The median household income around the school is $140,278 — nearly three times more than the Marion County rate, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“It’s just straight up segregation,” Damon TaZiyah told the IPS School Board Tuesday night. “It looks like segregation, feels like segregation. The numbers prove it.”

Concerns of segregation at district choice schools are not new. Nearly five years ago enrollment policies were tweaked as a means of providing more families access to the district’s most popular choice programs, such as the multiple Center For Inquiry and Butler Lab schools.

Then two years ago district leaders said they would revisit possible changes to the enrollment system after the earlier changes did not reduce concerns about equitable enrollment at some schools. Center For Inquiry School 84, a few blocks north of School 70, had an 83% white enrollment this past school year.

The lack of action by the district moved School 70 parents and Principal Christine Collier to urge for policy changes.

But the head of the nonprofit that manages enrollment at IPS says multiple factors in the enrollment system would need to be rewritten in order to improve diversity at some IPS schools.

Advocating for Enrollment Policy Changes

In the past academic year Collier began hosting regular Zoom meetings on racial equity with 30-40 multi-racial parents and guardians. But she didn’t expect the group to take off.

“In my vision, I was thinking, ‘OK, we’ll come together, and we’ll discuss the Nice White Parents podcast, or we’ll discuss some article or some of Paul Gorski’s work or something like that,” Collier said in an interview with WFYI last week. “And when the group came together, they really were an action-minded group. When the parents were meeting, it was like, ‘I don’t want to just come and talk. I want to look at what needs to improve, how do we take action.’”

A discussion led to how enrollment could be the cause of how the School 70 student population has become mostly white. So Collier invited various district employees to discuss the IPS enrollment system, the district’s racial equity initiative and the lack of Black educators in the district.

Before School 70 parents take on policies and practices within the building, they’re trying to see if they can first address the makeup of the student body so it doesn’t become an all white school. One way to alter the racial diversity could be eliminating the proximity priority.

“If you live five doors from a choice school that’s offering a great program International Baccalaureate, Montessori, etc. — and that appeals to you, we don’t want you not to be able to come,” Collier said. “We just don’t want you to be the only one that gets a chance to come.”

But even if the school removes the proximity priority boundary, Collier knows that might not change the makeup of the school.

“And [parents] realize, and I realize, just removing a priority boundary or advocating to do that may not change the diversity of the school because you need an applicant pool,” Collier said. “You need to advertise yourself and present yourself in a way that a large group of people want to apply and come to you. Otherwise, you could still be an all white school.”

Damon TaZiyah is one of the parents demanding changes to enrollment policies.

TaZiyah used to go to School 70 when he was in sixth grade, back in the late-90s, when it was not a Center For Inquiry program. That’s one of the reasons why he and his wife Brandi decided to enroll their children in CFI 70. But the school isn’t as diverse as it was then.

Three of the TaZiyah’s children have attended School 70 — their oldest just graduated from there. But their experiences at the school haven’t always been great. A teacher made microaggressions toward their two oldest children. Brandi said in follow-up conversations with the teacher, the educator admitted she targeted her son.

And the kid’s interactions with their peers have made lasting impacts. Sanai, 12, said she had to have a tough conversation about race when her now 7-year-old sister, Laila, said she wanted to be white.

“[Laila] said, ‘I just feel like white people — they get more advantages because they’re white,’” Sanai said. “And I was like, ‘Girl, you’re Black and you look beautiful. Black is beautiful. You don’t need to be white.’”

Brandi and Damon TaZiyah have even considered removing their children from the school. But they don’t want to be forced out. Instead, they want the culture at the school to shift.

That won’t be easy. There are five factors in the enrollment policy for School 70 that offer advantages to families who know how the enrollment system works. The factors include:

- In-district priority: a student who lives in IPS district boundary

- Sibling priority: a student who has a sibling already attending the school

- Proximity priority: a student who lives in a half-mile radius from the school

- Loyal applicant priority: a current IPS K-7th grader who did not receive their first choice in the lottery last year.

- IPS employee priority: the student’s parent works for IPS

Enrollment Trends

Bill Murphy, executive director of Enroll Indy — the school enrollment system used by the district — said the largest number of students who get into School 70 do so with either sibling priority, or a combination of both sibling priority and proximity priority. Murphy said a much smaller number of children gain entry with only proximity priority.

“I know that there are parents who think eliminating the proximity zone will solve a lot of problems,” Murphy said. “And it certainly would do something to make a school more diverse. But I think the real put-your-money-where-your-mouth-is-moment, is would they be willing to eliminate sibling preference if that meant maybe their younger children wouldn’t get into the school? If it meant that they would be inconvenienced?”

During the lottery for the 2021-2022 school year, 35 kids matched with School 70 during round one of enrollment for the kindergarten class. Of those students, 29 of them matched due to sibling preference. Only three of them were matched with proximity preference without the sibling priority. None of them matched in round one just based on the in-district priority.

Although Murphy said people can’t assume that all children within a given family are of the same race, it is more likely that they are. So in order to have the best chance of diversifying School 70, removing the sibling priority would have the greatest effect.

However, Collier and the TaZiyah family said they don’t want to remove the sibling enrollment policy because they don’t want to separate families.

The incoming kindergarten class at School 70 will be more diverse than in 2020-2021, Collier said. Because of sibling priority, it will have nine non-white students, one Hispanic and eight Black students.

Murphy encouraged families to research whether schools are prepared to serve and retain the diverse populations that could attend a school. For example, making sure a school is adequately serving the race, gender and learner profiles of students like their child.

“It is one thing to say we want more Black and Brown children [and] more low income children,” Murphy said. “And then it is an entirely different thing to have them show up and be underserved, or have them show up and face constant microaggressions from a population of teachers and students who are already at the school.”

The TaZiyahs admitted that they’ve benefited from the enrollment priorities. Since they do not live within a half-mile of the school, Brandi — an IPS district employee — doesn’t know if her children would have been able to attend School 70 if it wasn’t for the enrollment policy that provides priority to children of IPS staff.

What’s Next

Right now, parents are advocating for the proximity boundary policy to be removed at School 70 for the 2022-2023 school year lottery. But Collier and the TaZiyah family hope to later advocate for the boundary to be removed at the district level.

Collier said many of the white parents she’s spoken to want their children to grow up in a school and a community that “looks more like the city and the world, not just like the block they live on.”

IPS Board of Commissioners President Evan Hawkins is a School 70 parent, and has spoken to the parent group. But in an email response Saturday, he said he did not feel comfortable commenting on the subject at this time.

“It would be presumptuous to comment on the request to change CFI 70’s enrollment policy before it goes through the full process — which would include being presented to the IPS Board of School Commissioners for action,” Hawkins wrote.

IPS enrollment director Patrick Herrel said the district has started to see a plateau in the number of diverse students at choice schools. He said IPS is in the early stages of looking at the data and identifying reasons why this is happening.

Herrel said they are trying to incorporate any potential enrollment changes in their strategic planning.

“I think what we are trying to do is very holistically, as a district, look at all of the collective changes to how we utilize facilities, how we break up grade configurations, how students get access to different schools, what programming we have in what geographical locations,” Herrel said.

The district has not announced when the board may potentially address this issue.

Contact WFYI education reporter Elizabeth Gabriel at egabriel@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @_elizabethgabs.