What Indiana does and does not teach about government – such as constitutional amendments beyond the Bill of Rights – is back in the spotlight this week as the state moves forward with a new middle school civics course.

In civics across all grade levels, the state standards stop at the Bill of Rights, with no specific requirements for students to learn about subsequent amendments that abolished slavery and established equal protection under the law, as well as Indiana’s own history of legal discrimination.

In that vein, education advocates say the proposed middle school civics standards need more specificity, especially regarding the history of Black Americans and other people of color.

“How do we have time to talk about the Magna Carta and Rome, but we fully miss the contributions of other cultures to Indiana and to the nation?” said Marshawn Wolley, director of policy for the African American Coalition of Indianapolis. “If you’re not talking about slavery and the Civil War and Black men’s contributions to saving the union, you’re missing something.”

The standards are heading for a vote in June after nearly a year in development. But recent statewide debate about how schools should talk about race has sharpened the focus on what they’re missing.

Indiana quashed a bill earlier this year that took aim at classroom discussions of race and the legacy of slavery, amid ongoing national discourse about the teaching of hard history that has led states like Tennessee to pass several laws shaping and restricting curriculum.

While advocates are pushing for Indiana to require students to learn key moments in Black history, the state is reluctant to add specific examples to the new civics standards. State officials prefer to leave some decisions about content — such as that about the history of LGBTQ groups — in the hands of communities.

Whether that could create bias, or uneven learning, is a question that social studies teachers routinely grapple with, said Karrianne Polk-Meek, the department’s director of teaching and learning.

“Managing or thinking about the complexity of the students that they serve and the community they serve is inherently one of those things that teachers have to do every day,” Polk-Meek said.

Charity Flores, chief academic officer for the Indiana Department of Education, said including specific examples in the standards sometimes means those are the only examples that are taught.

For the middle school standards, the commission is considering offering additional resources for teachers that would give examples of how to connect historical events to the standards.

Asked whether those resources would include examples involving Americans of color and LGBTQ groups, Flores also deferred to school districts.

“The standards have always been defined to provide access to quality content for students and really should serve as a minimum threshold for ensuring that access,” Flores said. “There are opportunities where a local corporation may go above and beyond to describe other aspects.”

Creating new standards for middle school

The new middle school civics course is a product of a 2021 law authored by Rep. Tony Cook (R-Cicero), who this year wrote an unsuccessful bill to restrict the teaching of race and racism.

That bill, HB 1134, briefly crossed into civics with a requirement that students learn the importance of the U.S. Constitution compared to other systems of government, as well as about “individual rights, freedoms, and political suffrage.”

Under the middle school civics law, students will take the course in the second semester of their sixth grade year, beginning in 2023-24.

Department of Education staff presented the proposed standards for the course Tuesday to the Civics Commission — a 15-member body created by the law. The commission received 200 written public comments on the standards, according to Polk-Meek. The State Board of Education will vote on them in June.

The standards cover three areas: the foundations and function of government, as well as the role of citizens. Some specify texts that students should examine — such as the Magna Carta — while others ask students to broadly “examine ways that state and national government affects the everyday lives of people.”

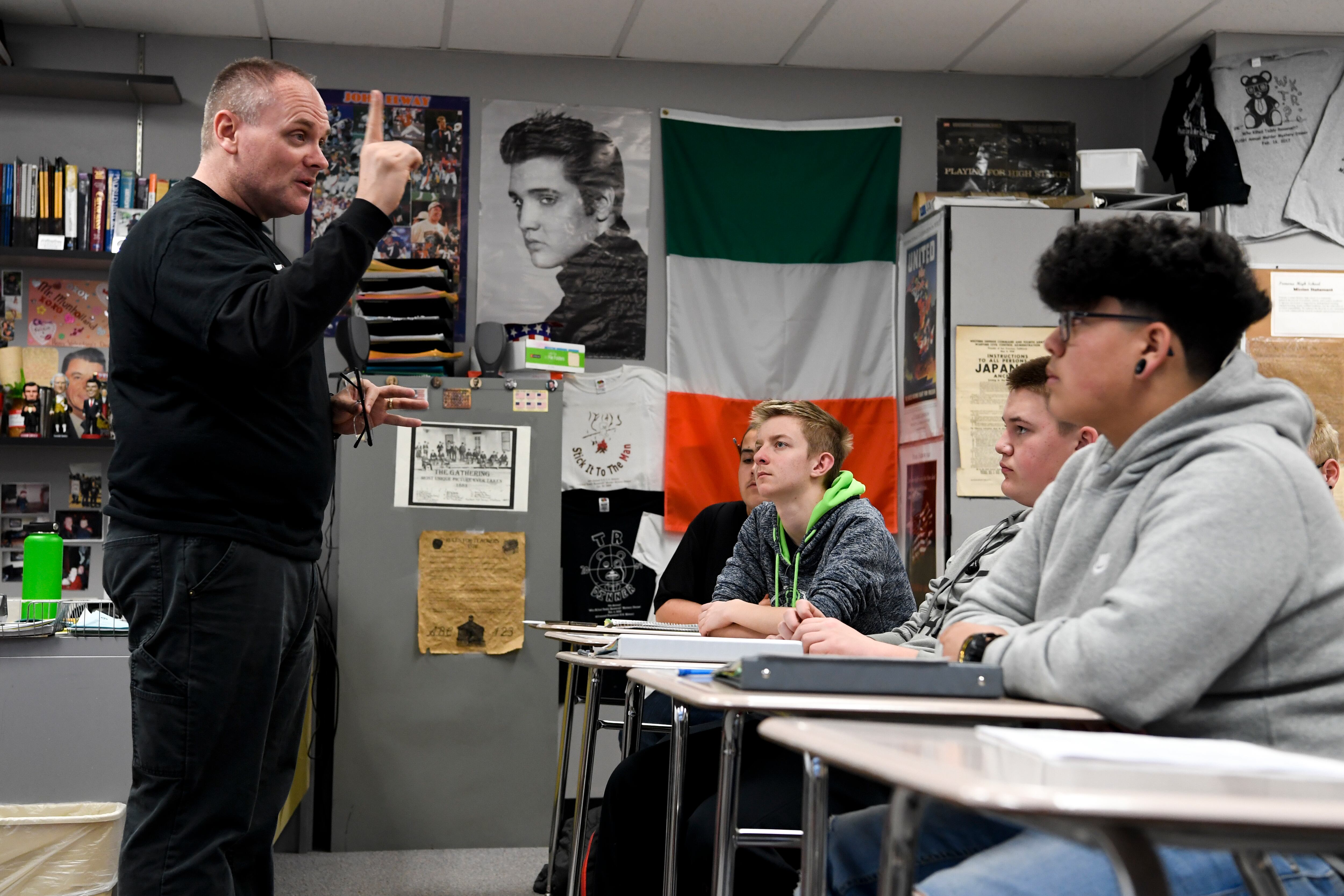

On Tuesday, Cook, a former social studies teacher, recommended adding more specificity to the standards, citing examples such as the pivotal Supreme Court rulings Brown v. Board of Education, which ended legalized school segregation; Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion; and Miranda v. Arizona, which upheld Fifth amendment rights.

He said that in his observations, the most successful social studies teachers built their courses around important historical documents and discussed the events that led to their creation.

Cook cited a 2021 analysis from the Fordham Institute, a nonprofit conservative think tank, that gave the state comparatively high marks for the quality of its civics and history courses, but knocked the standards for making no reference to the amendments after the Bill of Rights, and giving “little attention to Indiana’s past legal discrimination.”

The report notes that until high school, Indiana students primarily learn civics from their history classes. While Indiana history is discussed in fourth grade, the standards leave out the legalized discrimination of the early 20th century.

“By skipping the history of government in Indiana, the civics standards largely avoid important lessons about race and segregation, though one lonely history standard does address ‘the Civil Rights movement and school integration in Indiana,’” the report said.

Report stresses importance of specifics

The report recommends broadly that Indiana include more specifics in its standards, while ensuring that the 13th, 14th, 15th, 19th, and 24th amendments – which abolished slavery and established equal protection and voting rights – are covered at least once.

It also recommends additional content on Indiana’s past legal racism and the impact of the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause.

Indiana is not alone in neglecting the amendments that came after the Bill of Rights, according to Fordham Institute researcher Alison Brody. Ideally, states would include all the Reconstruction and voting rights amendments.

Amber Northern of the Fordham Institute said writing standards are a balance between being too specific — and bordering on curriculum — and not being specific enough — and bordering on uselessness.

For the most part, Northern said, Indiana has gotten the balance right, including with the new middle school standards. However, the standards would be stronger if they included specific examples, she said, and made it clear whether the examples were required.

Standard C.6.17, for example, asks students only to “use information from a variety of resources to demonstrate an understanding of local, state, regional leaders, as well as civic issues.”

A more complete standard such as C.6.5, she said, details the essential ideas students are expected to know:

“Identify and explain essential ideas of constitutional government, which include limited government; rule of law; due process of law; separated and shared powers; checks and balances; federalism; popular sovereignty; republicanism; representative government; and individual rights to life, liberty and property; and freedom of conscience and religion.”

Northern said including some examples is better than not including any at all, and that teachers appreciate the additional guidance.

Furthermore, she said there is a risk of inequitable learning outcomes when teachers have free rein to choose all their own examples, or none at all.

“The consequence of not teaching specific examples is that all students are not exposed to the same level of instruction and rigor in classrooms,” Northern said. “There should be an expectation that all students learn a core set of content.”

Department of Education spokesperson Holly Lawson said Indiana’s standards writing process involves input from parents, educators, and others. The current social studies standards were reviewed in 2020.

The state may take another look at its social studies standards by 2024 under a new state law that requires the department to evaluate the standards for value to employers and higher education institutions. It will consider feedback from stakeholders and third-party reviewers such as the Fordham Institute, Lawson said.

Some want Indiana to require Black history

Advocates have long pushed the state to require students to learn key moments in Black history.

In February, as the state inched forward on HB 1134, Sen. Eddie Melton (D-Gary) proposed an amendment that would have required high school history classes to teach an enhanced study of Black history, as they do the Holocaust. The amendment was voted down.

The new middle school standards represent another opportunity to require that history, advocates said.

The proposed standards don’t reference the 1851 Indiana Constitution, which included an article banning Black people from settling in the state, said Mark Russell, director of Advocacy & Family Services Indianapolis Urban League.

They leave out influential Hoosiers such as Sen. Birch Bayh, who authored the 25th and 26th amendments, as well as lessons about the presence of the Ku Klux Klan in state government, said Marshawn Wolley of the AACI, adding that he was concerned the civics commission lacked racial diversity.

Avoiding the lessons is detrimental to all children who are learning about the challenges and responsibilities of citizenship, Wolley said, but especially to Black children, who don’t see their history represented.

“These are clear examples of why you have to talk about all aspects of history,” Wolley said. “So you learn from the past and recognize that even when the country has made mistakes, this is still an amazing country, because we try to perfect the union.”

Correction: May 13, 2022: A previous version of this story misspelled Karrianne Polk-Meek’s name.

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.