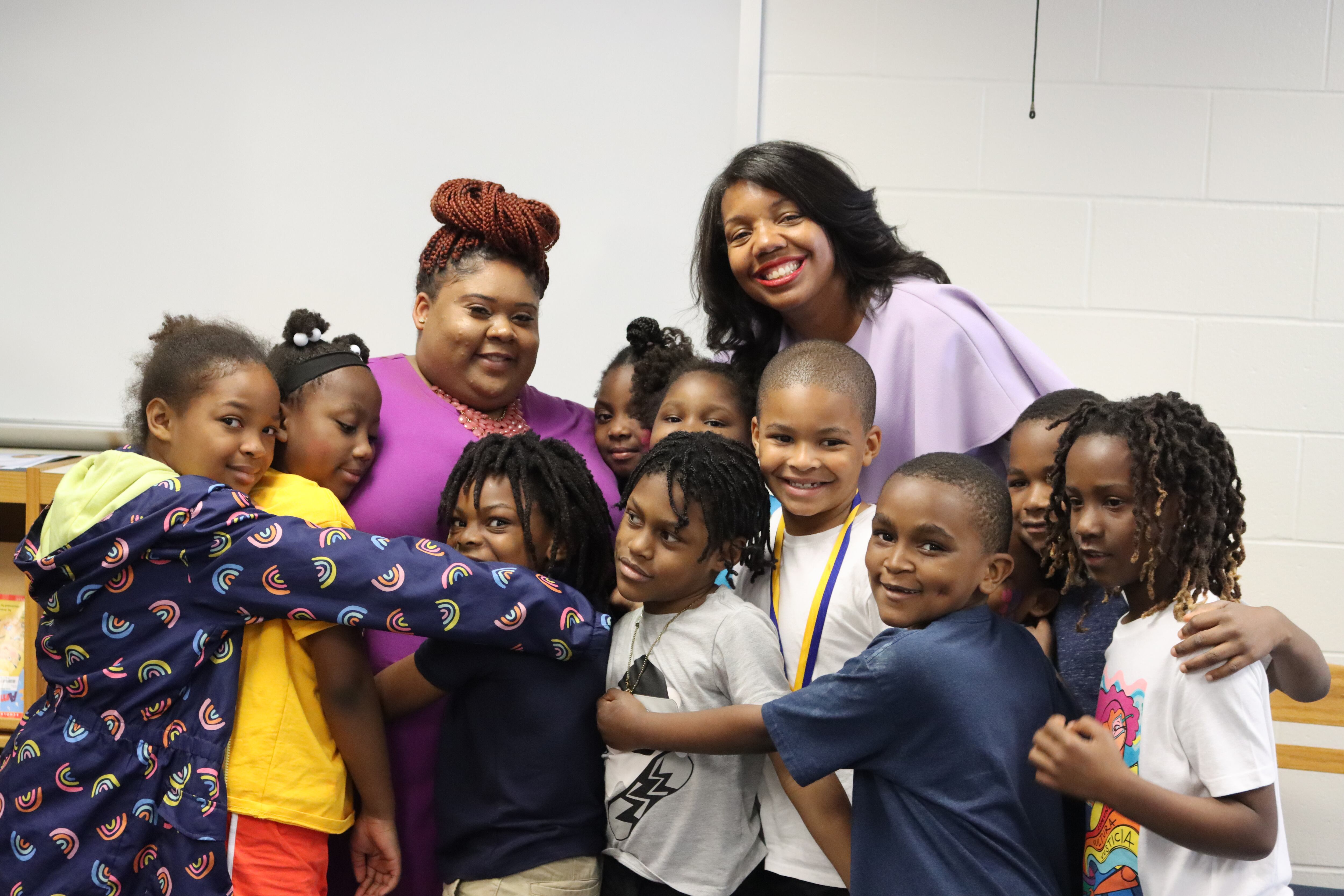

DaMeisha Fleming was named Indianapolis Public Schools’ Teacher of the Year in May, alongside fellow educator Paige Sjoerdsma. Fleming has taught first grade at James Whitcomb Riley School 43 for the past five years and worked as a mentor teacher for educators in the area.

Fleming says she has always loved mentoring children and works hard to create an environment where each student is supported with consideration for their unique needs. When she is not teaching, Fleming is studying to earn her master’s degree in Urban Educational Leadership at IUPUI or coaching student-athletes in sports such as volleyball.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

I was on the nursing track. I enjoyed the classes. I made the grade, but I just didn’t feel complete. I went over to the School of Education, and I was like, these are the courses that I’ve been taking — what does it look like? So, I met with a counselor and switched my degree track. As soon as I did that, I started loving to study, loving to be in the classes, and taking additional classes; it was almost like I was at home.

Following years of disrupted learning, is there anything you did differently this past school year to help students catch up and heal?

Well, I definitely think the pandemic played a role, but honestly, I’m an urban educational leader, so when there are a lot of things in place in our urban schools that were there pre-COVID. I think COVID further highlighted these disparities. What I have done differently is really stress the importance of the scholars and their learning. And we set goals, and we meet those because there is a shared understanding between teachers and students. This is where we’re growing.

What’s your favorite lesson to teach, and why?

February is Black History Month, and I go all out for Black History Month. Because my district uses a curriculum, it’s a little bit harder to be creative throughout the school year, but the month of February, I take that as my month to really connect with a lot of Black and brown students. I take that as a month to expose them to their history.

We look at the Underground Railroad and how brilliant our people were to come up with a system to escape different hardships. After that, we’ll take a look at our civil rights era. So we’re looking at figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks and Ruby Bridges. We look at our inventors and see how a world without Black people would not be such a great world at all because literally everything that we see, a Black person has had a hand in doing. Even when it comes down to the first open-heart surgeries and traffic lights. And students began to really see that I can truly be what I want because I stand on the shoulders of great people that have come before me.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your classroom?

Honestly, I would say social media is huge. A lot of times, things are happening on Instagram and Facebook, and then it is spilling over into the school. There’s just a lot of drama and different things like that, so it does impact our school greatly because it determines the mood and attitudes that the students come in on.

How do you approach news events in your classroom?

We do a meeting every morning, so that’s a time where we will greet each other. We like to acknowledge each other. It’s important to me that my students know that they are loved and welcome. And then after that, we talk about what’s going on. A lot of times, we’ll share how their night went or anything that stood out to them. We bring up current news [like when] one of our buses got in an accident last year. Some of my kids were on the bus; some were waiting for it to arrive. That’s something we talked about, and we use it in our circle. I allow the students to share. Because I teach first grade, we don’t go into a lot of details, but we definitely do share what’s happening in our world today and how it impacts our lives.

Tell us about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today.

Growing up, I did not have any teachers of color. All of my teachers were white. Another reason I chose this field is because our kids have to see themselves in these different positions. I think not having had a teacher of color really propelled me forward into the education field. Because I feel like you have to understand your students of color, and I feel like I missed that growing up.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received, and how have you put it into practice?

I will have to go back to my training at IUPUI in the urban educational program. It really prepared us for our urban environment because we get students from an array of different home lives, and so we do a lot of work around cultural pedagogy. One of the authors that we did a lot of reading on was Gloria Ladson-Billings, and she talks about the three tenets of being a culturally relevant teacher: You have to ensure that you have academic success. You have to make sure you have the cultural competencies and critical consciousness. When you merge all of those things together, then it informs your teaching, so that’s something I try to strive for and live by.

How has your role as a coach impacted how you approach teaching in the classroom?

I feel like there are a lot of parallels between how our students learn, whether it is a sport or it is reading. So, what I have found to be true is they have to do it first, and then they want you to come back and show them what they did wrong. So, for example, coaching volleyball, we would go over the basics: This is a set, this is a bump, but students were still not comprehending. Once you allow them to play their first game, they’re like, “Oh, that’s what we need to do.” Taking that into the classroom, a lot of the times, I’ll give them a task and say, “try this,” and let them come up with their different strategies. Then we’ll go back and review it.

Helen Rummel is a summer reporting intern covering education in the Indianapolis area. Contact Helen at hrummel@chalkbeat.org.