Indiana’s 2023 legislative session is under way, and state legislators have introduced more than 100 new education bills and bills impacting schools and students. For the latest Indiana education news, sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free newsletter here.

On a recent Thursday morning at KIPP Indy Unite Elementary in Indianapolis, a bus driver doubling as a tutor held up a flashcard to two elementary school students.

“What is this?” she asked.

The flashcard featured an illustration of a table. The students, a boy and a girl, piped up with answers.

“A door,” the girl said.

“No, that’s a table,” said the boy, earning a nod of approval. The tutor asked the pair another question: What letter does the word “table” start with, and what sound does it make?

The students quickly identified the letter. But taking its sound out of context proved more challenging. The tutor gave the students a few moments to guess before articulating the word herself.

“T-t-table,” she said, emphasizing the phoneme. The students repeated after her, connecting the letter “T’ with its sound.

At KIPP Indy Public Schools in Indianapolis, using bus drivers as tutors was an unusual idea spurred by the pandemic. In October 2022, when struggles with reading among K-3 students prompted the school to find solutions, KIPP started the program. Each morning, students are pulled out of class into the hallway for 10 to 20 minutes to practice literacy skills such as sight words and phonics.

It’s one approach to teaching using the science of reading, a body of research about how children learn to read. While some reading programs teach students to read by guessing a word based on a picture or using context clues, schools in Indiana and across the country are increasingly adopting curriculum that directly teaches the relationship between sounds, letters, and words.

In 2022, national reading and math exams showed only 33% of Indiana fourth graders and 31% of eighth graders were proficient in reading. These scores are similar to nationwide scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which revealed 37% of students performed below NAEP’s basic standard. The results underscore students’ struggles in reading that educators and lawmakers say is partially due to inadequate, outdated methods of teaching.

The consequences of flawed reading instruction go beyond test scores. Third graders who are not proficient in reading are four times more likely to not graduate high school on time or drop out completely, according to the Indiana State Board of Education’s Indiana Student Achievement Report.

Educators and lawmakers alike want to counter such trends. A major financial investment and a series of bills in the Indiana statehouse look to provide science of reading instruction to teachers, and some support mandating the science of reading within the state.

Science of reading emphasis grows in Indiana

Since 2011, Indiana has largely allowed school districts to decide which core reading program to use.

But one teaching method has been the target of significant criticism recently. The “three-cueing model,” which encourages students to make educated guesses at words using context clues, has been largely disproven by cognitive scientists but is still widely used by schools around the country.

Andrea Setmeyer, national chapter coordinator for The Reading League Indiana, said schools have traditionally failed to separate word recognition and reading comprehension.

“We’ve relied on strategies like guessing or looking at the first letter and thinking ‘what would make sense here?’ and those strategies are not what skilled readers do,” Setmeyer said. “What we need to do is look at those as two separate components that we’re building simultaneously.”

Karrianne Polk-Meek, director of the Literacy Center at the Indiana Department of Education, said the science of reading focuses on five key elements: phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

“Over time, some curriculum that has been used or different structures that have been used really reinforced some of the elements, but not necessarily all five,” she said.

Several states have already implemented or are looking to implement the science of reading in schools, many of which have shown significant improvements in reading rates.

Nearly a decade ago, Mississippi fourth graders ranked 49th in the nation for reading proficiency. But after the state hired literacy coaches and focused instruction around the science of reading, it was ranked first in the nation for reading gains by 2019.

While the research behind the science of reading has been around for decades, Setmeyer said such knowledge has often been confined to fields like cognitive psychology and linguistics, rather than education, where teachers could benefit from it.

But following encouraging results from states like Mississippi — and American Public Media’s “Sold a Story” podcast, which investigated authors who push disproven teaching methods — the science of reading is gaining traction.

Last August, Indiana announced a $111 million investment in literacy through a partnership with the Lilly Endowment. The investment — the state’s largest-ever commitment to literacy development — supports training educators in science of reading instruction, and incorporating science of reading methods into undergraduate teacher preparation programs.

The Indiana Department of Education also launched a partnership to place reading coaches in 54 schools across the state to support K-2 teachers as they lead instruction rooted in the science of reading. Currently, 43 schools are participating in the pilot program, and more are being recruited for the 2023-24 cohort, Polk-Meek said. (KIPP is not part of the program.)

Indiana mulls changes to teacher prep and licensing

Lawmakers are considering whether to go a step further.

Senate Bill 402, authored by GOP Sen. Aaron Freeman, would prohibit schools from using the three-cueing model and require them to adopt curriculum based on the science of reading. The bill would also require people to pass foundational reading exams to get a teaching license.

Freeman, who has two children under 13, said he was inspired to write the bill after seeing the struggles students like his own faced when it comes to reading.

“These kids are not going to learn by guessing,” he said. “They’re only going to learn if they have phonemic awareness, if they’re able to sound words out, break words down.”

If Freeman’s legislation, which has passed the Senate, becomes law, it would go into effect for the 2024-25 school year.

Other proposed bills also address the science of reading: House Bill 1558 creates a science of reading grant fund, while House Bill 1590 includes teacher preparation and licensing requirements for the approach.

The second bill underscores that putting the science of reading into practice across the state would mean not only a shift in how students learn, but how teachers learn, too.

Kelly Williams, an assistant professor of special education at Indiana University-Bloomington, said she was taught outdated research during her training in the mid-2000s.

“There was kind of this general consensus of, if you expose kids to enough books and find what they’re interested in, you’ll be able to get them reading,” Williams said. “That’s really problematic — we’ve got teachers coming out who are not being trained in what best practices are or what research actually supports.”

Williams said there should be an emphasis on language comprehension, not just knowing what a word is. Reading is not fully natural, she said — students must be taught to read.

KIPP began using the science of reading in 2021 after assessing pandemic-related academic gaps.

Ruth Wells, foundational literacy manager at KIPP, said the science of reading makes education cohesive by tying together how language is developed in the brain and how students learn words and sounds.

“That gives teachers the ability to, one, pinpoint where their students may have gaps, but also a spoken sequence to follow to make sure they are teaching what they know their students need,” Wells said.

To truly comprehend text, Wells said, students must be able to decode words, not just identify which word might fit using only context clues.

Data from KIPP showed 74% of kindergartners have met mid-year goals after being taught using science of reading-based practices — an 8% increase from before the program. Among first graders who received that instruction, 70% met the goals, a 21% increase, and 46% of second graders met them, marking an 11% increase.

Teachers and drivers join forces to teach science of reading

Each summer, teachers at KIPP participate in training where they learn why the science of reading is important. During the training sessions, they can practice portions of their lessons to receive real-time feedback from other educators.

“Our teachers are learning to be experts and we do a lot of development with our teachers, but again, there are different levels to kiddos,” she said. “Our tier–1 instruction can be as strong as anything, but if a kiddo comes to us and needs that extra support, we need to be able to supply it.”

Bus driver Tracie Johnson has been with the tutoring program since its start. In addition to tutoring Monday through Thursday, Johnson gives her students a test each Friday to gauge their growth and identify areas of progress or struggle earlier than formal state tests can provide results.

This also gives teachers more time to teach the actual curriculum rather than worry about testing, which can take hours.

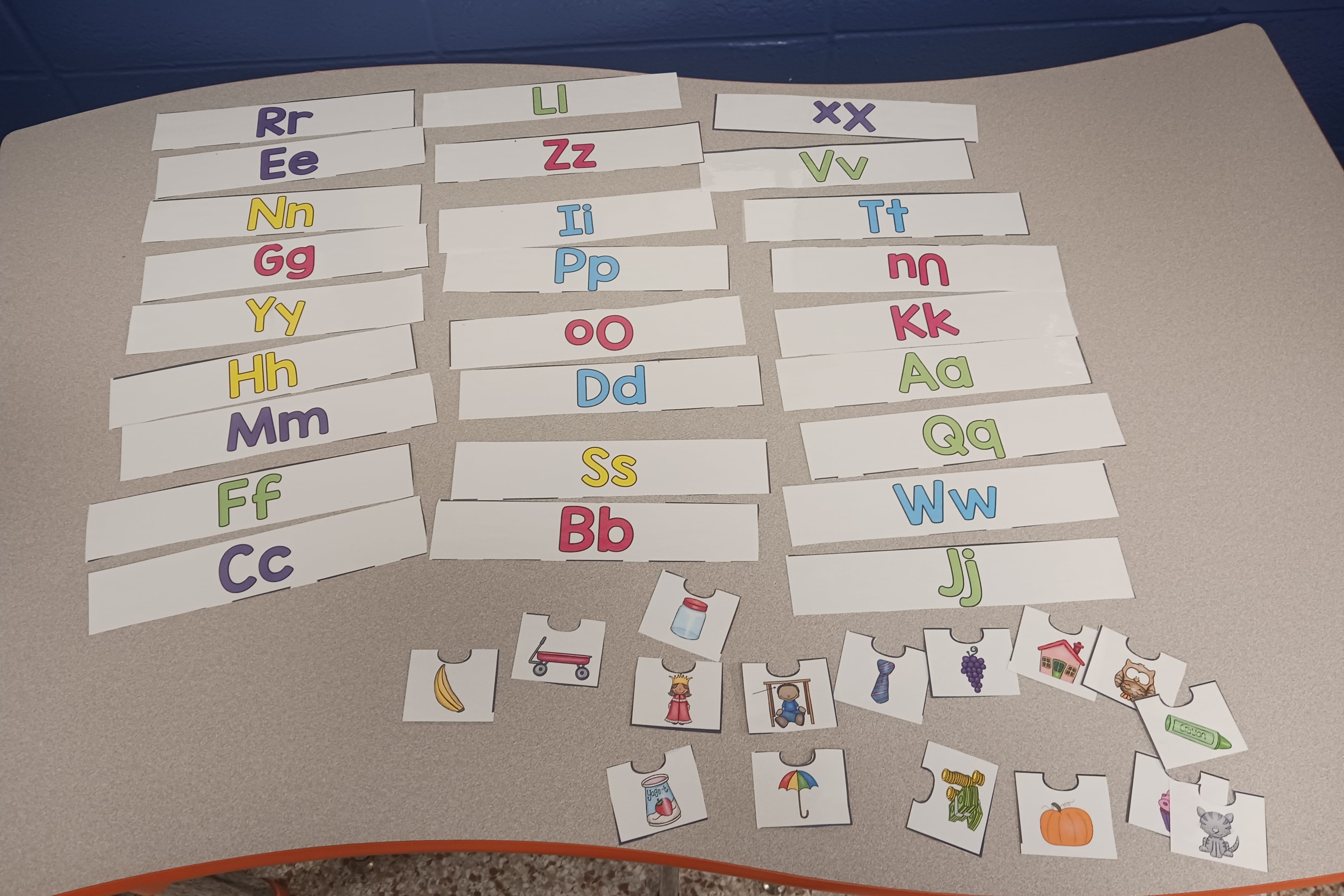

Using data from state literacy tests such as IREAD along with weekly classroom tests, teachers identify students who could benefit from extra review. From there, bus drivers build activities with the help of teachers based on the specific skills each student needs to practice. These activities often include using flashcards, coloring sight words, and trying to beat the clock in fluency races.

Each grade level is given a benchmark per year — 100 sight words for kindergarteners, 200-300 for first graders and 500 for second graders.

“If a student is a kindergartener and he’s still struggling with letter names or letter sounds, our bus drivers would be working with those particular students who didn’t get it the first round and maybe the classroom instruction has moved forward,” Wells said.

At a time when hiring bus drivers and other school staff has been difficult, the tutoring program has also helped the school retain drivers, thanks to the increased connection they feel with students, Wells said. Plus, they clock in for the role, earning more money in addition to what they get for their regular routes.

KIPP’s strategy would not be guaranteed to work for every school for a variety of reasons. Union rules that could affect such instruction differ among districts and states, for example. And participation could depend upon whether drivers receive pay increases.

Eight drivers are currently participating in the KIPP program, with many more undergoing training. There has been over 300 hours of tutoring in the program so far.

Johnson enjoys working with the students, and it’s particularly rewarding when they finally get a word or concept correct, she said. Before the program, many of her students could not even spell basic words like “the,” she said.

Now, those students speak up to offer correct answers to her questions.

The best part of the job, Johnson said, is connecting with her students for longer than a bus ride. When they run to her each morning to give her a hug, she’s reminded of the difference she’s making in their education.

“That’s the highlight of my day,” she said.

Contact Chalkbeat Indiana at in.tips@chalkbeat.org.