Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

This article was co-reported by Chalkbeat Indiana and Axios Indianapolis as part of a reporting partnership about youth gun violence in Indianapolis.

How do you save the lives of teenage boys who act like they aren’t afraid to die?

City officials are looking into it. Police are asking for help. Kareem Hines and his mentors keep trying.

“We, unfortunately, lose kids a lot,” said Hines. “The positive stories, the successes that we see with the kids, keep us going.”

Hines’ New B.O.Y. program — short for New Breed of Youth — is one of several in Indianapolis trying to reverse an alarming statistic: the highest number of youth homicides in at least six years, the majority of which involve guns. Some young men he works with are saved. Others are not, and Hines sees them on the news. Last year, the program lost six participants who ended up dead or in prison.

Either way, week after week, Hines and his team of mentors try to give their young men something to live for.

New B.O.Y., which began in 2009 and works with about 125 boys, is based on the mantra of “connection before correction.” It’s built on consistency.

Youth martial arts classes are on Tuesdays. Boxing classes are on Saturdays. There are field trips to go skiing or visit college campuses. And nearly every Wednesday, there are group talking sessions called “leaders circle” that bring children and parents together to review the week’s good and bad events.

Hines knows himself the power of a mentor and constant engagement from growing up in Harlem with a single dad. He met his own mentor at the YMCA, where he got his first job at 15. That mentor was the reason he moved to Indianapolis at age 20 in 1995, when he got a job at the Fall Creek YMCA that has since closed.

Since then, Hines worked in various mentoring and community outreach programs until launching New B.O.Y. in 2009.

But understanding just how challenging New B.O.Y.’s mission is means understanding the world in which the program operates.

It’s one in which teenagers pose smiling with guns on Instagram. Students “go 30″ — fight each other — in the school bathroom just to see who wins. Flyers circulating online promote parties that combine social media fights and guns in a confined space. “Drill” rap music describing shootouts with enemies is popular.

And embedded in all of this is the trauma of living in poverty, growing up in high-crime, under-resourced neighborhoods, or nursing broken relationships with adults.

Hines emphasizes that his program isn’t a cure-all.

“We’re just a piece of the puzzle,” he said. “We understand the plight of these young men, so we try to stand in the gap in every area, but we can’t be with them 24 hours a day.”

The program draws strength from youth like Patrick Collier who succeed.

As he’s grown in New B.O.Y. from a jaded pre-teen in foster care to a budding entrepreneur, Collier, now 18, has closely known four fellow participants who’ve been killed and two who’ve been locked up.

Losing them, he said, is more like losing a brother — and at times he did not want to come to New B.O.Y. activities for fear of learning of another person was dead or arrested.

“Ultimately, I realized that if I’m losing people this much, that just means that I have to do something,” said Collier, who hopes to study social work at Indiana University Bloomington next year. “I have to wrap my hands around the people that are in the program.”

Talk sessions offer teens tough love, understanding

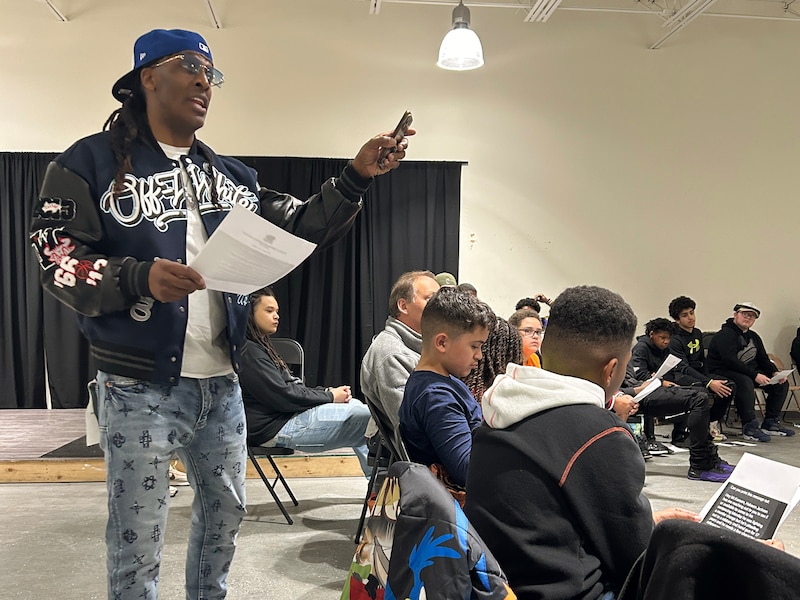

Hines is both a fiery preacher and understanding therapist. When he talks, these teenagers listen.

It’s a method of engagement with youth that he’s honed over decades of working with them.

In the leaders circle sessions that last for hours, he invites participants to describe the environment in which they live. He asks them to explain their poor decisions but celebrates their wins. And he tries to wrap it all up in a message of love and understanding.

The program’s participants are typically referred through the state’s Department of Child Services or the local probation department, but some can come from community-based referrals as well. The majority of the participants, like the majority of the city’s homicide victims ages 19 and under, are Black.

There’s the young man with a penchant for yo-yos who has lacked a strong female presence in his life and struggles with anger issues. But he celebrates his weekly wins at circle sessions — in January, he reported, he’d “been thinking about what I do before I do it.”

There’s the teenager in and out of juvenile court system who, under New B.O.Y.’s guidance, wrote a memoir sharing his family trauma.

During a leaders circle session in October, when Hines asks how easy it is for him to obtain a gun, he doesn’t hesitate: “It’s easy as 1, 2, 3.”

“I’m tired of that life” on the streets, he said. “I’ve been in that since I was nine. I’m 15.”

Hines frequently acknowledges the lack of fathers in the boys’ lives. He nods to the fact that adults have let them down. And he often asks the group questions that everyone knows the answer to. In this way, he and other mentors signal that they understand where these boys are coming from.

“Should you feel uncomfortable at a teenage party in this city?” he asks during one session in January. Yes, the boys nod, because you might get shot.

“What’s ‘catching a face?’” he asks after playing a drill rap song through a loudspeaker at an April session.

It means killing somebody, they answer.

But these sessions also feature important life lessons.

Hines frequently passes out the latest articles of teenagers arrested for murder or killed in shootings, asking the boys to read it aloud and assess what the subjects should have done differently. In one session, he encouraged the boys to play chess, not checkers — in other words, to think critically about their decisions.

And during another session in January, the boys heard from JaMarcus Fields, who served 26 years in prison for murder.

“The system is not playing while we out here trying to play tough,” Fields said. He described his first night in prison as a scared 18-year-old.

“I literally went to sleep a little kid and had to wake up the next morning a grown man,” he said as the boys sat listening quietly. “I didn’t have a choice.”

Some boys still end up in prison — or worse

Still, not everyone makes it through New B.O.Y. alive or living life as a free man.

Hines uses every loss as a teachable moment.

In February, the boys stared at a text message about a former New B.O.Y. participant, now in his twenties.

“[He] has me reaching out to you to see if ur available to come to his sentencing Monday,” the message read. “He was fighting a murder charge but he’s pleading out.”

But Hines laments the fact that he hasn’t seen the young man come back to the program in a long time.

“He needs a few character references — can I give him a character reference?” Hines asks the group.

The boys shake their heads.

“Hell no. Hell no,” Hines said. “Hell no, I can’t.”

Still, Hines and the mentors keep going, even when participants stray from the flock. Stopping is not an option.

“I got about another 10 to 12 other young men who are still pushing, who made a different decision,” he said. “So we got to be there for them.”

Celebrating wins and giving boys ‘an incentive’

Collier was a frustrated middle school student when he met Hines at around 12 years old.

Years of being in and out of multiple foster homes left him standoffish, lacking trust in adults, and acting out in school. But the night that Hines showed up at his foster family’s house, wearing clothes that someone his age would wear, Collier was taken aback.

“He’s real,” Collier said on why young men respond positively to Hines. “There’s no facade he puts up. There’s nothing he tries to do that isn’t him. There isn’t an agenda oriented around profit that he works on.”

New B.O.Y.’s constant programming is what drew Collier out of his shell and ultimately earned his trust. He joined the program’s Young Entrepreneurs Program and launched a nonprofit with a fellow New B.O.Y. participant to bring food, clothing, and other services to those in need.

And like Hines, the programming felt authentic.

“It was never like, ‘Hey, let’s get this photo and then we’re going to drop him off,’” he said. “It was really genuine. I mean, there were rarely any cameras around. There were rarely people that weren’t always locked into the program.”

Outside of the tough love that New B.O.Y. participants get in the leaders circle, Hines and his team of adults are there year-around to provide the positive life experiences Collier had.

On a sunny Saturday in November, uplifting music is bumping on the field next to what used to be Indianapolis Public School 11. The young men huddle in excitement with mentors as they review their plays in the annual flag-football tournament against Evolve, another mentoring group.

“I keep an incentive in front of them,” Hines told Chalkbeat. “No matter what, I want to keep them with some kind of hope.”

New B.O.Y.’s programming aligns with Hines’ philosophy of correcting poor behavior while still actively celebrating life and its successes. He dislikes grandiose celebrations of life that occur only after a child has been killed. And he laments when news crews come to him for interviews only after someone dies.

He frequently calls on parents to be more involved with their children, not only through the bad, but the good.

“If you don’t love yours, and wrap your arms around yours, the streets will,” Hines told families at New B.O.Y.’s annual awards ceremony in December.

At the ceremony, boys in the martial arts program came up to the stage. Like a drill sergeant, Hines made the students answer him back, repeatedly:

“Who do you believe in?” he shouts. “Myself,” they answer.

“Who do you love?”

“Myself.”

Read the Axios Indianapolis story here.

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Lawrence Township schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.

Arika Herron is a reporter for Axios Indianapolis. You can reach her at Arika.Herron@axios.com.