Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

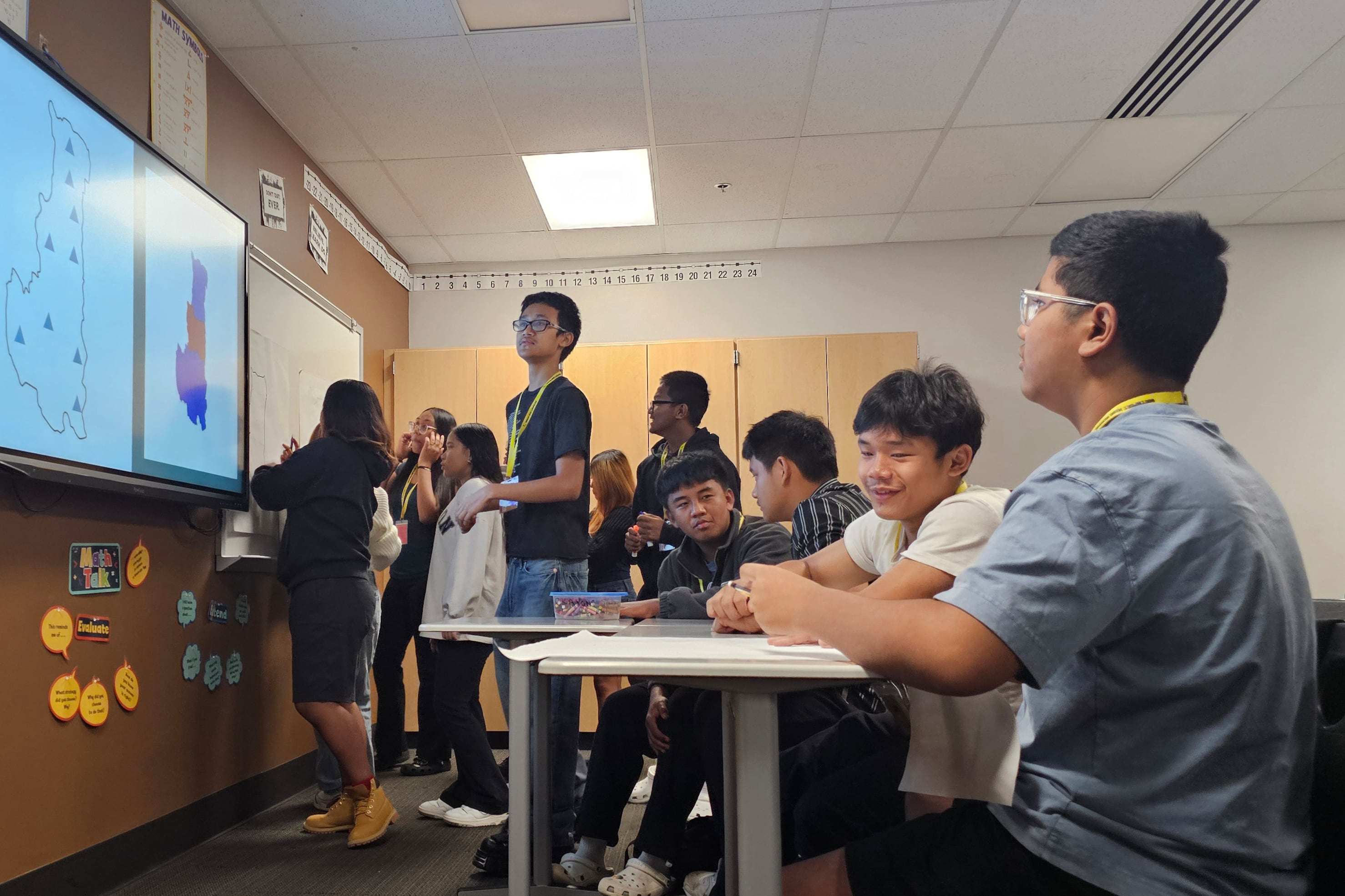

For some students in Sui Tial’s class, drawing a map of the Chin State of Myanmar is the first time they’ve looked closely at the country their families fled.

Born in the United States, these students may only speak a few words of Hakha, or the Chin language, Tial said.

But other students who were already fluent speakers also wanted to take the Chin heritage language class at Southport High School, the first such offering in Indiana. Tial asked them why.

“They said, because we don’t know our culture. We don’t know how to practice it. We don’t know how our community is doing,” Tial recalled. “And I said, okay, that’s the reason we’re offering this class.”

Beginning this year, Perry Township schools will offer heritage language classes in Hakha Chin at both Southport and Perry Meridian High School in order to serve students from the large and growing Chin community. Unlike foreign language classes, heritage language classes are designed for students with some familiarity with a language, like hearing it at home. Spanish heritage language courses are offered at districts throughout Indiana, including Perry, Lawrence, and Washington schools.

For Perry students, the class is an opportunity to connect with Hakha-speaking family members, including relatives still living in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma.

Nearly 4,400 students in Perry schools — or more than one-quarter of all students — speak a language from Myanmar; around 3,700 speak one or more Chin dialects. The district had hoped to offer a Chin language course for years, but struggled to find a teacher qualified to teach it, administrators said.

“I can speak Hakha, but I can’t really write in Hakha. I’m trying to learn how to write, that’s my goal,” said freshman Amos Cung. “When I text my family, I’m usually writing in English.”

The Chin community south of Indianapolis is one of the largest communities of Chin immigrants in the world, many of whom arrived during decades of conflict in Myanmar. The Chin Community of Indianapolis estimates the population at 30,000 people.

For Chin immigrants, who may not have learned to read and write in the language after it was banned from schools in Myanmar, the class is a way to give their U.S.-born children that opportunity, said Julie Zing, executive director of the community center, which helped develop the course.

“We never really had a chance to learn the Chin language, reading and writing, in school. Basically, we had to learn it from churches,” Zing said. “Now, what we’re facing is that the parents don’t speak English and the children don’t speak Hakha. It’s a huge concern.”

Churches in Indianapolis hold language classes for students over the summer, Zing said. But there’s a limit to how much they can cover in a few weeks.

“This is a year-long class, and we think that’s a really cool thing,” Zing said.

A refugee from Myanmar who arrived in the United States in 2009, she worked as a tutor and translator in Perry schools. Then, before she left for college and earned her teaching license, she wrote a letter to her Southport administrators telling them that she’d be back as a full-fledged teacher.

It’s a path that Perry administrators hope more support staff and even students will take.

“We want more teachers who are multilingual,” said Jane Pollard, the district’s assistant superintendent overseeing secondary schools. “The diversity is what makes us special, and supporting that and students is important to the district, because students who are literate in their native languages, it’s easier for them to be literate in English, too.”

Tial travels between the two high schools to teach both sections of the Chin heritage language class. This year, Tial volunteered to build the Chin heritage language program at the district on top of her Algebra 2 and geometry classes.

One challenge was establishing a base of knowledge with her students, some of whom grew up in Indianapolis, others in refugee camps in Malaysia.

That’s why they started with the geography of the Chin state, Tial said. Next week, they’ll begin learning the alphabet.

She relies on English to communicate with her students now. But she hopes that by the end of the year, they’ll be able to converse in Hakha amongst themselves, and even write short sentences.

“If they don’t understand, how will they know what’s going on in the community?” Tial said. “We want them to communicate with their parents and the community, and we want the community to be more connected with Perry Township schools.”

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.