Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

After working at a summer camp for children with muscular dystrophy when he was 16, Andrew Bova knew he wanted to teach special education. But getting to the classroom would take some turns.

Bova enrolled at Ball State in 2012 to pursue an education major but did not pass a section of the PRAXIS test necessary to take upper-level courses. A retake led to similar results.

Taking the test a third time would mean delaying his graduation, so Bova chose a new major that led him to a career teaching preschool and then working with young adults and children in the Department of Child Services.

Still, Bova felt drawn to special education. That coincided with an urgent need for special education teachers after Indiana was found to be in violation of federal law for allowing teachers on emergency permits to teach special education.

The solution was I-SEAL, a program from the Center of Excellence in Leadership of Learning at the University of Indianapolis that allows current teachers, including those on emergency permits, to get fully licensed in special education at no cost.

The program is funded by Indiana’s federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief II funding and Part B of Indiana’s Individuals with Disabilities Act funding, according to Indiana Department of Education spokesperson Courtney Crown.

And with the federal relief dollars expiring, the department plans to advocate for funding for teacher pipeline programs when the legislative session begins in January, Crown said in a statement.

More than 1,100 teachers have enrolled in the program, and nearly 600 have completed it since its inception in 2021.

That includes Bova, who had started teaching special education at Perry Meridian Middle School on an emergency permit.

The program allowed him to stay in the classroom while completing his licensing requirements — a major boon for school districts already struggling to hire special education teachers, said Dana Vittorio, director of special education at Perry Township schools.

After completing his education through the University of Indianapolis in 2023, Bova expects to be a fully licensed special education teacher beginning next semester.

“I wanted to be a teacher to influence and make an impact. I’m finally here — it took a long roundabout way to get to where I’m at,” Bova said.

‘Putting a dent’ in teacher shortage

The I-SEAL program offers three tracks for individuals who are already in the classroom. They must have a teaching job at a district and agree to teach in Indiana for at least two years to enroll in the program.

Licensed teachers can add a special education endorsement through fully funded tracks at University of Indianapolis, Taylor University, or Indiana Wesleyan University. Individuals with bachelor’s degrees can receive a full scholarship to a Transition to Teaching program, and other scholarships are available for students enrolled in a special education teacher preparation program.

The program is not currently open to people who don’t have bachelor’s degrees. But CELL Executive Director Carey Dahncke said developing a path to teaching for people who earned some college credits may be another way to fill teaching vacancies in the state.

“There’s still a great need in Indiana,” said Dahncke. “We’re putting a dent in it, but we’ve still got a ways to go.”

A recent presentation from the department said there hasn’t been an “alarming” number of individuals leaving the education profession, but there are fewer aspiring teachers entering into and completing teacher prep programs.

At Perry, hiring has been getting incrementally better every year since the pandemic, said Vittorio, the director of special education. This year, the district’s special education teaching roles are 100% fully staffed — a first since before the pandemic, when many teachers chose to retire.

Still, she said it’s a far cry from years that schools would receive 30 applications for every teaching position, she said. Statewide, there are 287 open special education teaching positions as of late October on Indiana’s teaching jobs board.

Vittorio said the I-SEAL program has been critical to staffing; Perry schools has had eight teachers enroll in or complete the program. She encourages teachers to consider the program and earn their special education teaching licenses for free.

“Now we’re a little more creative. We can find really talented people and help them get their licenses,” she said. “It’s not just benefitting the district but benefitting our kids, because those teachers help our kids meet their goals.”

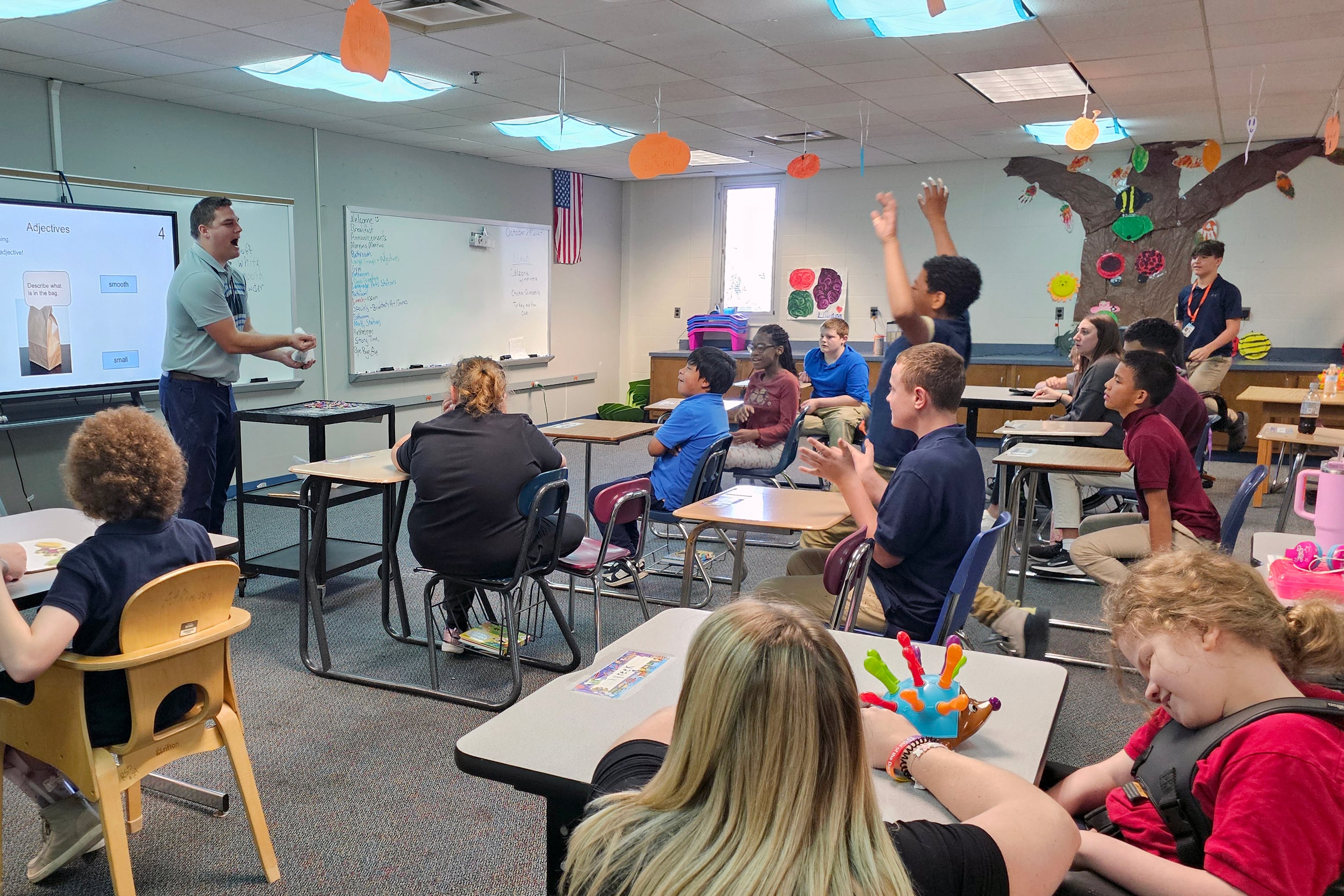

Inside Bova’s class at Perry Meridian Middle School

In Bova’s self-contained classroom, he teaches students with disabilities such as autism and Down syndrome. On some days he helps them use wooden blocks, magnetic tiles, or shaving cream to write letters and words.

On Tuesday, he led them through a lesson on adjectives and inferences using mystery objects in four paper bags. The students reached in and offered descriptive words to help their peers figure out what was inside.

The lesson isn’t just fun — students chanted “Dump it out!” as Bova prepared to reveal pumpkin seeds and paper clips — but serves a practical purpose for when the class starts writing sentences next week.

Bova said that to this day, he applies lessons he learned through the I-SEAL program, like strategies to teach his students phonics and literacy. He also values the support of other educators in his cohort, who still talk and exchange ideas via group chat, he said.

Though it took him longer than expected to land a job teaching special education, he said all his previous experience helped him learn to advocate for his students, beginning with that first camp counselor role.

“It opened my eyes to what the day-to-day looks like for these kids and their parents, how vulnerable they can be, but what opportunities are available to them,” he said. “It’s about what they can do, not what they can’t do.”

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.