Thousands of Newark students have already missed multiple school days this year, newly released data show, even as the district’s new superintendent makes improving attendance a top priority.

About one in five students missed more than a week’s worth of class during the first three months of school, according to the district data. Those roughly 8,000 students are already considered “chronically absent.”

Newark has long grappled with exceptionally high rates of chronic absenteeism, which is defined as missing 10 percent or more of school days in an academic year for any reason. Students who miss that much school tend to have lower test scores, higher dropout rates, and greater odds of getting in trouble with the law.

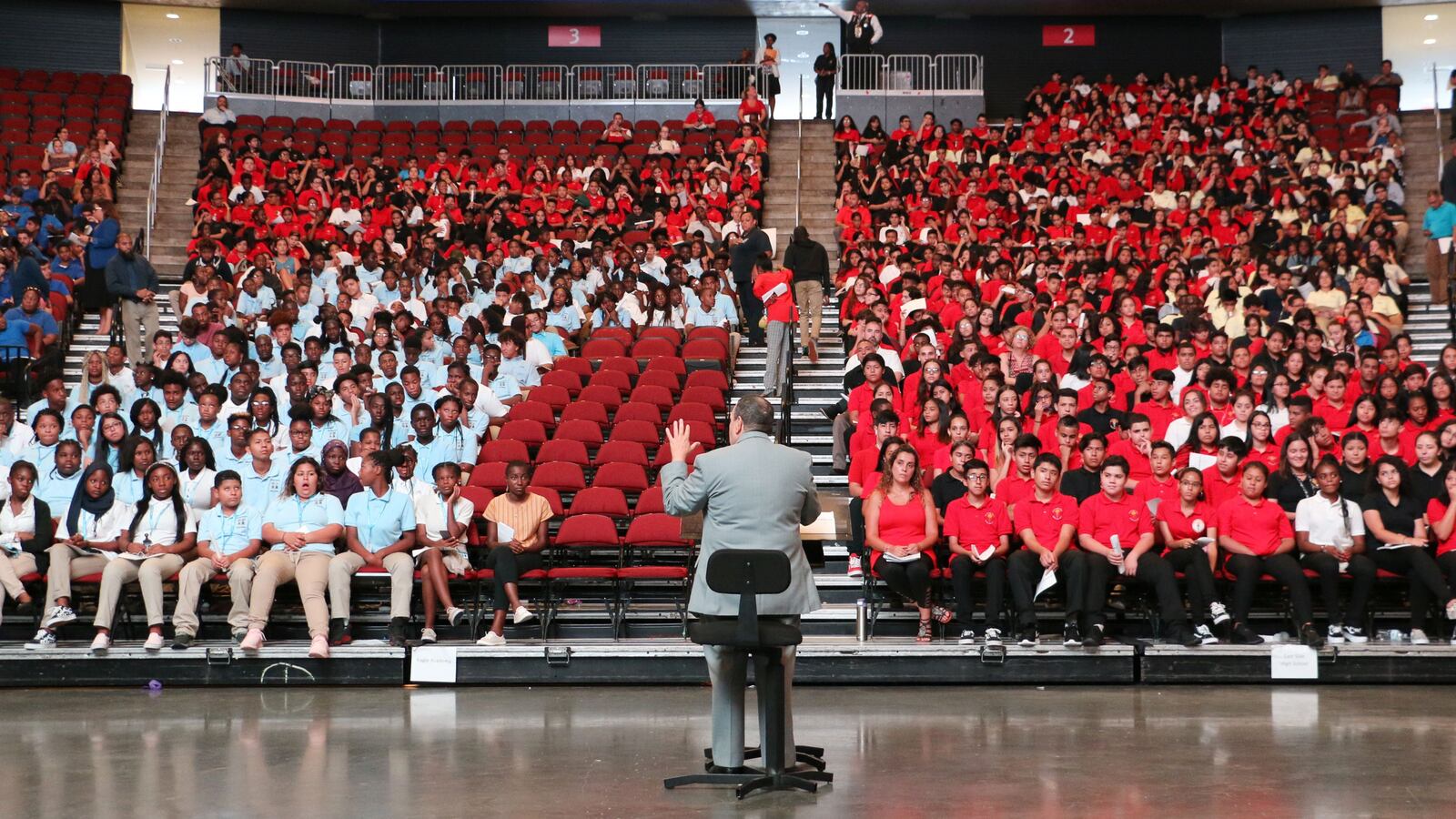

The district’s new superintendent, Roger León, has promised to attack the issue — even going so far as to set a district goal of 100 percent attendance. But the new data, which León released this week, show how far the district has to go.

Nearly 9 percent of of the district’s 36,000 students have already missed the equivalent of more than two school weeks, according to the data. Those 3,200 or so students are labeled “severely chronically absent.”

Experts say that tracking and publicizing attendance data, as León has done, is the first step in combating absenteeism. Now, some district leaders are calling for the next phase of work to begin — analyzing why so many students are missing class and taking steps at the district and school level to help get them to school.

“It’s great that we have all this great data,” Newark Board of Education member Kim Gaddy said at a board meeting last month. “But if you have the data and you’re not using the data to change the situation, we won’t do any justice to our children in this district.”

Students who missed six or more school days from September through November qualify as chronically absent. If they continue at that pace, they are on track to miss the equivalent of a month or more of school by June. Students who missed 10.5 days or more during those three months count as severely chronically absent.

The early data show that Newark’s long-standing absenteeism patterns are continuing. The chronic absenteeism rates over the past three months were about the same as in 2016, according to the data.

The problem remains most acute among the district’s youngest and oldest students: 41 percent of pre-kindergarteners were chronically absent this November, as were 45 percent of 12th-graders. At least a third of students at five high schools — Barringer, Central, Malcolm X Shabazz, Weequahic, and West Side — were severely chronically absent last month.

While absenteeism rates varied among schools, they tended to be highest in the city’s impoverished South Ward.

“I’m concerned particularly about the South Ward,” Gaddy said at the Nov. 20 board meeting. “That’s where our children need the most assistance.”

León, a former principal who became schools chief on July 1, has already taken some early steps to improve attendance.

His most visible effort was a back-to-school campaign called “Give Me Five,” where he ordered every district employee to call five families before the first day of school. The campaign, for which León himself recorded robocalls to families, appears to have made a difference: 91 percent of students showed up the first day, the highest rate of the past four years, according to district data. (In 2013, when former Superintendent Cami Anderson launched her own attendance campaign, about 94 percent of students attended school the first day.)

The district also eliminated some early-dismissal days, which typically have low attendance. And students with mid-level test scores whom León has targeted for extra support have had better attendance this year than their peers, officials said.

However, León hit a snag trying to enact the crux of his attendance plan — reinstating more than 40 attendance counselors whom Anderson laid off years ago to cut costs. The state’s civil service commission has said the district must offer the jobs to the laid-off counselors before hiring anyone new, León told the board — forcing the district to track down former employees who, in some cases, have moved to different states. Only eight counselors have been hired to date, but León said he hopes to fill the remaining positions next month.

Meanwhile, León is arguing that some of the responsibility for improving attendance falls on families. At November’s board meeting, he said some parents and guardians “believe that, in fact, they can keep their children home” from school. At a parent conference this month, he took that message directly to families.

“I don’t care if school ends at 10 and they’re only going to come for an hour, and half an hour is on a bus,” he told several hundred parents who showed up for the daylong summit. “When I tell you that your child is coming to school, it’s your job to make sure the child comes to school.”

Afterwards, several parents and school employees said they welcomed León’s tough talk on attendance.

“It was about parents ensuring kids are in school and they are doing good,” said Bilikis Oseni, who has a child in first grade at Camden Street School. “Attendance is very key.”

Still, Newark families face many obstacles in getting their children to school, according to a 2016 report on chronic absenteeism among young students. Parents cited a lack of school busing, asthma and other childhood health problems, and work schedules that make it hard to drop off their children in the morning. High school students listed uninspiring classes, mental-health challenges, and safety concerns when traveling to school as reasons why they don’t show up, according to a 2017 report.

At the November board meeting, several members asked León whether he planned to dig deeper into the causes of absenteeism.

“I was looking through all the statistics here in the packet,” said Andre Ferreira, the board’s student representative, who attends Science Park High School. “But there were none that looked towards having a survey of students themselves telling you why they aren’t coming to school.”

León noted that he held forums with high-school students in September where he stressed the importance of showing up. He also said he has a student-only email address that some students have used to explain why they miss school.

“So I’m gathering data that lets me know why a particular student in fact hasn’t been to school,” he said. “Ultimately, we would have to do that for every single student, in every classroom, in every grade, in every school. That’s really the work — and it’s hard to do.”

Peter Chen, who co-authored the two reports on chronic absenteeism in Newark, said the superintendent had taken a crucial first step by raising awareness about the city’s attendance challenges. The district also appears to be sharing attendance data more regularly with schools, he said.

The next step is for the district to help schools identify and assist students who are chronically absent. The central office can do that by sharing effective attendance strategies, training school workers on how to support students’ social and emotional well-being, and offering grants to fund schools’ own attendance campaigns, he added.

“This is something that requires tailored, school-level responses,” said Chen, who is a policy counsel for Advocates for Children of New Jersey. “The district can help support some of that — but it’s not something that’s easy to impose from on high.”