One evening last week, excitement surged through the Willing Heart Community Care Center, a charity housed inside a Baptist church near downtown Newark.

Dozens of residents had crowded into the pews for a chance to listen to some of the 13 candidates vying for three open seats on the city’s school board. They understood the high stakes of next month’s election: Newly empowered after two decades under state control, the nine-member board will be responsible for managing the district’s nearly $1 billion budget and choosing a new superintendent.

This group of board members “will be the first set under the newly constituted Board of Education,” said Deborah Smith-Gregory, president of Newark’s NAACP, which hosted the event, as the crowd rumbled with applause. A few moments later, she underscored her point: “This becomes a very, very important election.”

But for all of the election’s significance, it’s hardly expected to be a model of democracy.

Held in April apart from other elections, voter turnout — like school board races across the country — has historically been low. Last year, about 7,500 people cast ballots, or just over 5 percent of registered voters.

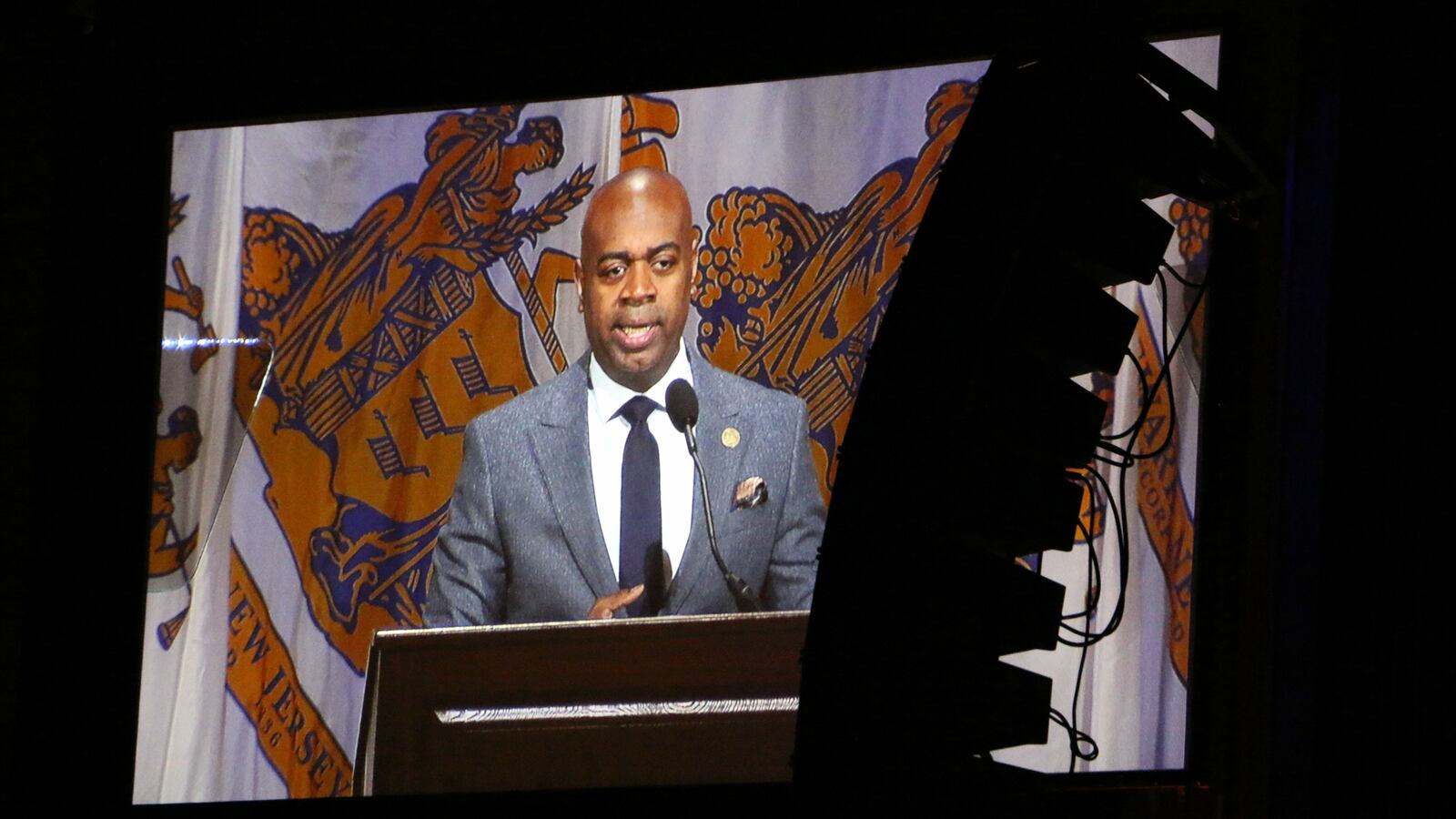

And three of the candidates are running on a slate backed by a powerful alliance of Mayor Ras Baraka, North Ward Councilman Anibal Ramos Jr., and the city’s growing charter-school sector. Candidates on that slate — previously dubbed “Newark Unity,” and now called “Moving Newark Schools Forward” — have dominated each election since the alliance formed in 2016.

Charles Love, a former parent organizer who ran in the previous two board elections, said the 10 candidates not on that slate face an uphill climb. Last year, Love had committed volunteers and the backing of a city councilwoman. But he said it was not enough to compete with the political machine behind the Unity slate, which helps its candidates fundraise, knock on doors, produce campaign materials, and prep for debates.

“In a sense, the Unity slate negates the independent candidate — it creates almost zero possibility of you winning,” Love said. “If you try to throw arrows at a tank, you’re going to lose.”

Below is a guide to the power centers behind the slate whose candidates are considered the leading contenders in this year’s election, which takes place April 17. (The deadline to register to vote is March 27.)

A muscular charter sector seeking to mobilize parents

As Newark’s charter-school sector has rapidly expanded to serve about a third of city students, its political ambitions have grown with it. That was made clear by its recent search for the ideal school-board candidate.

A coalition of charter-school advocates convened by the Newark Charter School Fund first identified nearly 20 potential candidates last summer. The contenders then participated in individual and group interviews, met current board members, and underwent trainings on how to run for public office. One session was conducted by Democrats for Education Reform, a national pro-charter advocacy group led by Shavar Jeffries, a former Newark school-board member and mayoral candidate.

Finally, the coalition settled on Asia Norton, a Newark parent and kindergarten teacher at KIPP Life Academy charter school.

“We think she is smart, talented, and has the right experience, temperament, and leadership to represent all of the 55,000 kids in Newark,” said Michele Mason, the Newark Charter School Fund’s executive director.

The charter sector began to ramp up its political involvement after Baraka’s election in 2014. During the campaign, he had crusaded against former Superintendent Cami Anderson — whose policies included opening more charter schools — and attacked Jeffries, who enjoyed strong backing by pro-charter forces.

The following year, supporters of the city’s largest charter-school operators, KIPP and North Star Academy, funded a new advocacy group called the Parent Coalition for Excellent Education, or PC2E. The idea was to organize the thousands of Newark parents with children in charters into a potent voting bloc that could push back against critics who wanted to halt the sector’s expansion.

In 2016, PC2E joined the “Newark Unity” slate with Ramos and Baraka – a surprise given that Baraka had sharply criticized Newark’s charters for sapping resources from the district’s traditional public schools. PC2E’s political arm spent heavily on the board races — nearly $208,000 in 2016 and over $174,000 in 2017, according to campaign filings — and its candidates easily won each year. (PC2E has been less active since its executive director resigned in November.)

Now, charter advocates are focused on getting Norton elected. For her part, Norton is emphasizing her local roots — she grew up in the South Ward, and her mother is a Newark public-school teacher — over her charter credentials. At Thursday’s candidate forum, she touted her experience teaching for six years in Newark schools but did not mention that they were charters.

“I don’t view myself as a charter teacher,” Norton told Chalkbeat in an interview before the forum. “I’m a Newark teacher.” She said parents should be able to choose the best schools for their children – whether public, private, or charter.

“That’s what I think makes Newark so rich,” she said, “all the different educational programs that are provided for our children.”

A ‘pragmatic’ mayor running for re-election

Baraka has long been a force in the city’s school-board elections.

The “Children First” slate that he backed as a city councilman and then as mayor won seats in five consecutive elections, according to the election-tracking site Ballotpedia. In many of those races, his candidates battled those on the “For Our Kids” slate, aligned with the powerful North Ward.

So when he joined the Unity slate in 2016, many saw it as a shrewd political move. The alliance allowed him to choose a candidate who stood a strong chance of winning without having to take on the North Ward machine or the well-financed charter sector, whose schools serve a growing number of city residents.

“Mayor Baraka is very astute, he’s very pragmatic,” said Antoinette Baskerville-Richardson, the mayor’s chief education officer. When it came to the board elections, she explained, his options were to “be inclusive or wage a war of finances, organizing, and mobilization.”

This year, his chosen candidate is Dawn Hayes, a City Hall staffer and public-school parent.

According to her campaign biography, she is a former member of the U.S. Air Force and “the first Muslim woman working as a technician for Direct TV.” She is also a member of the Newark Anti-Violence Coalition and president of the Harriet Tubman school’s parent-teacher organization.

Even as Baraka pushes for his slate to win in April, he is looking ahead to May 8, when he is up for reelection. While he is heavily favored in that race, a school-board victory ahead of time would help lend an air of inevitability to the outcome.

“Is it a barometer for the mayoral election?” said Baskerville-Richardson. “I guess so.”

A ward known for its political prowess

When it comes to racking up votes, the North Ward is a well-oiled machine.

It was long under the sway of Steve Adubato Sr., a political powerbroker who founded the North Ward Center in 1970 and one of New Jersey’s first charter schools, Robert Treat Academy, in 1997. Now Councilman Ramos, who ran for mayor in 2014 before dropping out and endorsing Jeffries, is one of the main forces behind the ward’s political operation.

In last year’s school-board election, slate candidates received far more votes in the North Ward than they did anywhere else — including Baraka’s base in the South Ward.

This year, Ramos’ chief of staff, Samuel Gonzalez, is chairing the Moving Newark Schools Forward slate. Ramos himself is bringing its members along as he canvases at churches and community events ahead of his own re-election bid in May.

“We really take the election seriously,” Ramos said about the board race. “We take it as an informal test of our operation.”

The ward’s candidate is Yambeli Gomez, an aide to Councilman At-Large Eddie Osborne.

The daughter of immigrants, Gomez previously was an organizer for campaigns to raise the wages of fast-food workers and expand pre-kindergarten in New York City. Her mother is an organizer for the powerful 32BJ SEIU union.

Introducing herself at last week’s forum, Gomez switched between English and Spanish — a nod to the city’s growing Hispanic population. Consistent with her slate, she sounded a theme of unity.

“I’m running for school board because I was one of those kids who didn’t feel included,” she said. “I want to be able to help and be inclusive.”