It was a tale of two Newark school systems.

At a monthly school board meeting last week, Newark’s schools chief played up the positives about the state’s largest school district, where he said “dreams are coming true,” and highlighted good news such as an uptick in enrollment. In stark contrast, community members sounded the alarm about dire problems posed by the pandemic: students with disabilities going without mandatory services, frustrated teachers resigning, and students struggling with trauma and severe learning loss.

The elected school board, which regained full control of the district last year after decades of state management, mostly went along with the superintendent’s upbeat assessment, asking few questions even after district officials shared new test scores showing that the vast majority of students need intensive support in reading and math after a chaotic year of remote learning. The board also did not discuss recent reports about the lack of drinking water in some Newark schools and questionable uses of the district’s COVID-recovery money, or follow up on previous calls for the district to post COVID case counts online, which it still has not done.

“I just feel humbled hearing all these wins,” said board member A’Dorian Murray-Thomas during the Nov. 23 virtual meeting, adding that students are thriving despite having “big hills to climb.”

Some members of the public said the discussion minimized the huge challenges hanging over the district.

Denise Cole, a Newark Public Schools graduate and former school board candidate, said it’s important to celebrate Newark students’ many accomplishments. But, she told the board, officials need to spend less time “giving each other accolades” and more time publicly discussing the many difficulties students face as they try to rebound from the pandemic.

“The very people who are employed in the schools are telling you what is going on,” she said at the meeting, and it “is contradictory to all of the information that you all give out in public.”

Some of the information that district officials shared was undeniably encouraging. The district, with some 37,000 students, has managed to prevent serious COVID outbreaks this fall and keep all schools open, officials said. Several new schools are up and running and the district’s student population grew slightly this year, the officials added, defying a national trend of shrinking enrollments.

“We have 700 more students than even last year,” Superintendent Roger León said during the meeting. “Why? Because people understand that it’s about getting a really good education and voting with their feet.”

But other data painted a less rosy picture.

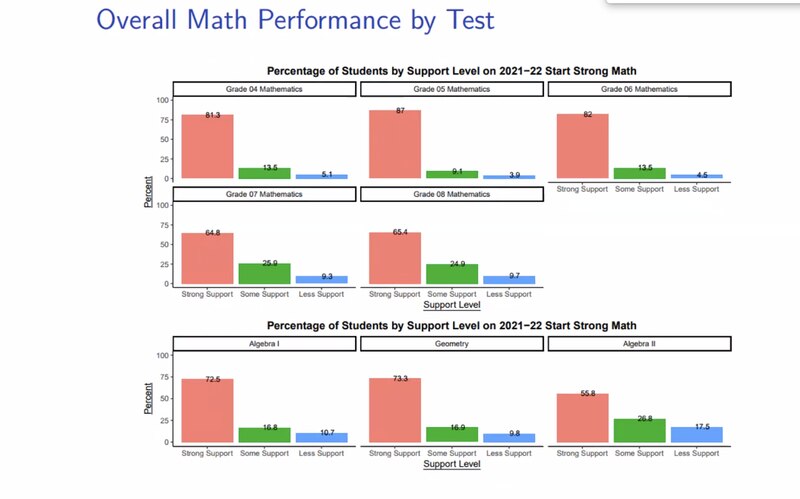

As required by the state, officials shared the results of a mandatory new test called “Start Strong,” meant to gauge students’ academic needs after the pandemic profoundly disrupted their education. Echoing previous test results, and in line with national data showing that low-income students of color suffered the biggest setbacks during remote learning, the new test showed that many Newark students are struggling. For instance, 81% of fourth graders and 65% of eighth graders landed in the lowest score range on the math test, indicating that they need “strong support.”

After the scores were shared, León acknowledged, “We have a lot of work to do.” But he didn’t explain how the district would help students recover from the learning loss; he referenced tutoring, but did not say what it will entail, which students will participate, and how or if the district will measure its impact. Instead, he made winding remarks about various education efforts.

“I also want you to know that whatever work the students were doing at home and the importance of getting them back into school and the work that teachers were doing throughout the whole entire time and with tutoring opportunities, that we are slowly and surely and aggressively moving the academic programming with changes,” he said during the virtual meeting, where several of the nine board members kept their cameras turned off most of the meeting.

Board President Dawn Haynes agreed that the district must do “incredible” work to catch students up, but did not give or ask for details about that work. Vereliz Santana was the only board member to explicitly ask the superintendent how he plans to support students’ academic recovery, including his planned use of millions of dollars in federal aid meant to help schools address learning loss. León simply said the district does not plan to “remediate,” but to offer demanding courses such as algebra and calculus.

“We are poised to be doing what we’re doing at the point of time that we’re in right now,” León said at the end of his presentation.

Such vague assurances did not satisfy the district employees and community leaders who signed up to speak at the meeting. One after another, they described acute challenges in the schools that were not included on the meeting’s official agenda — and demanded meaningful answers.

Christopher Canik, a high school teacher and union leader, said some students with disabilities are being shortchanged services, and teachers “are treated like we are not professionals.”

Vanness Roper, a Newark pastor and education advocate, said many schools are “out of compliance” with special education laws.

R. Jamaal Gourdine, who identified himself as a district employee, said students are “crying out” for better school meals, classrooms are overcrowded, and “staff are overworked, some even resigning.”

Kathleen Witcher, a district alumni group leader, noted that the district spent some of its pandemic recovery money on security cameras and floor polishers, which are not “remedies that work directly on learning loss.”

Yvette Jordan, a high school teacher and member of the teachers union executive board, said she was “extremely concerned” by the district’s failure to test school water for lead, which Chalkbeat revealed in a story published shortly before the meeting. Because the district only started testing for lead this month, according to board documents, many school water fountains remain turned off, leaving some teachers and students to supply their own water.

And Wilhelmina Holder, a Newark Public Schools graduate and longtime parent advocate, said district officials need to provide details about academic support for struggling students and data on the programs’ impact.

“We can’t just applaud each other,” she said, “and we have nothing to back that up.”

After the public comments, board member Hasani Council asked the superintendent to assign someone to record the public’s questions and track down answers. When he’s out in the community, Council added, people ask why their school concerns aren’t being addressed.

“The community’s holding us accountable,” he said. “It’s our job to hold the superintendent accountable.”

Haynes welcomed the suggestion, saying the district will start posting responses to the public’s questions.

“We try to focus on transparency and honesty within our district,” she said.