Until recently, Fs were piling up at Newark’s Central High School.

On Jan. 10, the school of roughly 770 students recorded nearly 2,000 failing grades, according to staff emails reviewed by Chalkbeat. That day, a district administrator sent Central’s principal a list of all the students with Fs or missing grades, calling it “an action item that requires immediate attention.”

Two days later, the principal, Dr. Sharnee Brown, issued a school-wide directive: Get rid of the Fs.

“During the pandemic, no student will have missing grades or Fs,” read a slide in a presentation shared with teachers on Jan. 12. Instead, every student was expected to complete the second marking period, which ended Thursday, with a C average or better, the slide said. It called the order a “NO F & Missing Grade MANDATE”.

Schools across the country reported alarming failure rates this fall as students struggled to learn remotely during a relentless pandemic. In Newark, where district officials have not formally changed the grading policy, high schools have instituted ad hoc measures to stem the tide of Fs. The efforts range from offering extra tutoring to giving “incomplete” grades to, in Central’s case, apparently barring Fs completely.

Central’s approach reflects the view of many experts and educators that schools should show students grace during a terrible time. Yet some teachers worry the no-F mandate goes too far, leaving students unprepared for later coursework while papering over the full extent of lost learning.

“In the long run, I think we’re hurting the kids,” said a Central teacher, one of three who discussed the school’s grading policy on the condition of anonymity to avoid retaliation.

Central students could raise their grades by attending tutoring or completing assignments during “Catch Up Wednesday sessions,” the principal’s slide presentation said. But the presentation also suggested other grade-boosting strategies that sounded more like quick fixes than academic improvement.

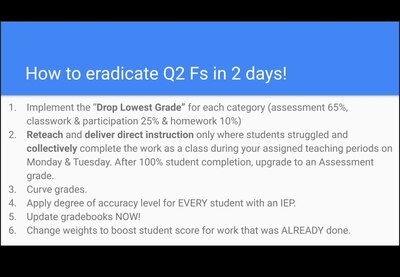

Teachers could let students complete assignments “as a class” instead of on their own, drop students’ lowest grades, or give extra weight to work students already submitted, another slide said. Its title: “How to eradicate Q2 Fs in 2 days!”

By the end of January, nearly 1,200 Fs had disappeared, leaving 774 in the grading system, the emails show.

Some teachers were troubled. They had no problem letting students make up missing work and retake assessments. But passing students who rarely — or never — attended class or submitted work felt dishonest, they said, and could set up students to struggle in subsequent courses or college.

As educators, “you help students as much as you can” to earn passing grades, said a second Central teacher. “What is extremely upsetting is that, when students are a no-show, we’re being told: No Ds or Fs.”

Dr. Brown did not respond to an email requesting comment.

District spokesperson Nancy Deering did not explain the “action item” email sent to Dr. Brown listing students with failing grades, but she said the matter is under review. She added that the district has not changed its grading policy, which allows teachers to give Fs when warranted.

“The schools are required to follow the district’s grading policy,” she said in an email.

Schools grapple with Fs

Schools nationwide are wrestling with the same dilemma as Central: How do you grade students during a pandemic that has disrupted nearly every aspect of their lives and learning?

Some schools were able to dodge that question last spring when districts such as New York City, Chicago, and Denver suspended their usual grading policies to account for the unexpected shift to remote learning. Newark did not change its A-F grading system, but urged teachers to be “flexible.”

This school year, most districts reverted to their typical grading practices, partly to signal that school is still in session even if classrooms are closed. But even as grading returns to normal, school has not.

Many districts, including Newark, remain fully remote, and the challenges that dogged some students last spring — including unreliable Wi-Fi access and distractions at home — continue. Meanwhile, many young people report feeling increasingly isolated and exhausted the longer remote learning drags on.

Now, teachers in Newark and elsewhere are agonizing over the Fs in their gradebooks. While they are loath to fail students who fell behind during the pandemic, they also are wary of passing students who showed little evidence of learning. The tension is especially acute in high schools, where grades appear on official transcripts and signal whether students are ready for advanced courses and college.

“Whatever you’re teaching, you’re making a commitment to certify that a student has mastered certain content and skills,” said Ron Chaluisan, executive director of the Newark Trust for Education and a former high school principal.

During the pandemic, teachers should be flexible with assignments and offer students extra support — but they shouldn’t automatically pass everyone, he added.

“I think there are things you still have to hold kids accountable for,” he said.

Many Newark students have endured staggering hardships during the pandemic, from inadequate food and unstable housing to family members falling ill, while others have taken on jobs and child care duties.

Aware of those challenges, Central High School has gone to great lengths to assist students. Teachers and other staffers have delivered laptops when students needed them, checked in when students missed class, and offered tutoring when they fell behind. Still, about 20% of Central students were chronically absent in December, according to district data.

Some teachers say they don’t feel comfortable passing those students who have disengaged from class.

“If a kid only hands in two assignments, how do I justify giving him a C?” a third Central teacher said. “To me, that’s not helping anybody.”

Yet school administrators have insisted that all students should pass this marking period — even those who did not meet basic requirements, the teachers say.

“It’s crystal clear, it’s not ambiguous,” the first teacher said. “Even if that kid doesn’t show up, you have to find a way that they don’t fail.”

Kanileah Anderson, whose daughter attends Central, said students had ample opportunities to make up work and get tutoring. If they still didn’t do the bare minimum, she said, then they shouldn’t pass.

“I don’t agree with, ‘We’re not going to fail anybody,’” she said. “It just sends the wrong message.”

Failure as a last resort

The policy at other Newark high schools is that Fs should be a last resort during the pandemic — but they aren’t forbidden, teachers said.

“The word has been that nobody should be failing if at all possible,” said Christopher Canik, a math teacher at Newark Vocational High School. But, he added, “No one’s come to me and said, ‘You absolutely cannot fail a child or give them a D.’”

Canik said he works with struggling students during lunch periods, and allows them to earn extra credit through an online math program. Students who miss class can also watch videos later to get caught up. As a result, most students earned at least a D last quarter, Canik said.

Al Moussab, a history teacher at East Side High School, said he has given struggling students “incomplete” grades and extra support instead of Fs. Like other teachers, he is weighing how to show students grace during the crisis without lowering his standards.

“We’re not benefitting the child just from advancing them,” he said. “But these are extraordinary times.”

The principal of Barringer High School, Dr. Jose Aviles, sent an impassioned memo to teachers this week making a case against Fs.

Failing students who have experienced trauma and poverty and entered Barringer far behind will not advance their learning, he wrote. And the nationwide spike in Fs during the pandemic will have negative effects “felt for decades.”

The memo instructed teachers to give students who complete any work at least a D. Teachers who feel a student deserves an F must complete a “failure justification form.”

Dr. Tanya Maloney, an assistant professor of teaching and learning at Montclair State University, said passing every student won’t benefit those who didn’t learn the material. But she echoed many Newark educators in calling this moment an opportunity for schools to rethink their grading systems.

“We’re having to ask ourselves what is fair,” she said, “in a way we weren’t before the pandemic.”