Joicki Floyd woke up early one morning last week just before Newark rumbled to life. She folded laundry while her children slept, savoring the quiet she knew wouldn’t last. At 8:30 a.m., it was time for school.

Floyd, who teaches ninth-grade English, logged into a video chat and waited for her students’ faces to appear. Her 11-year-old son, Sir, was nearby getting ready for his online school. Her 8-year-old daughter, Donnell, sat beside Floyd on the well-worn living room loveseat, mother and daughter each with laptops balanced on their legs. Any barrier between Floyd’s personal and professional lives had long ago collapsed.

After a few minutes, she texted some students: “Where are you?” As they started to arrive, she complimented one student’s new hairstyle and told another to turn on his camera. Only six of 10 students showed. But that’s typical for virtual school during the pandemic, so Floyd launched into her lesson.

This week will mark one year since the families of some 36,000 Newark Public Schools students got a Friday evening phone call saying school buildings would be closed for at least two weeks. The next day, Newark reported its first confirmed coronavirus infection.

Twelve months and more than 880 deaths later, there are hopeful signs in Newark. The daily death count has dropped from dozens at its peak to the low single digits, and more residents are getting vaccinated every day.

Yet it’s jarring just how much hasn’t changed. As two weeks turned into 52, Newark remains one of a dwindling number of districts across New Jersey and nationwide where classrooms are still fully closed. Teachers still are giving lessons remotely. And some students — including many of Floyd’s — still are not showing up.

Over the past year, Floyd watched the virus tear through the city where she was born 45 years ago and grew up, where she is now raising her own children and teaching others. She watched the disease strike down her neighbors and colleagues, adding to the list of COVID-19 casualties who are disproportionately Black and Hispanic.

She watched her teenage son graduate high school last spring without prom or commencement. And she watched her students at Weequahic High School in Newark’s South Ward wrestle with fear, loneliness, and boredom as the pandemic gripped the world and wouldn’t let go.

Through it all, Floyd kept teaching. She gave lessons on “Native Son” and “Romeo and Juliet” over video, responded to students’ texts and emails late into the night, and trudged through the snow to track down teenagers who went missing. What became clear is that the skill she had sharpened over 20 years of teaching — her gift for connecting with students and drawing out their inner strength — had equipped her for this all-consuming crisis.

“This is what I do,” she said in August, one of a series of interviews that started last spring. “If I didn’t do it, I would feel frustrated. I would feel empty. I would feel like I’d be cheating my community and the children.”

Everything changes

Joicki Floyd settled on her life’s mission when she was still a child.

Growing up in Newark’s South Ward, she listened to her mother tell stories from her own childhood, when she faced abuse at home and bullying at school. Floyd decided then to protect and nurture young people.

“If I could save children,” she recalled thinking, “it would help me deal with the fact that my mom was a child who no one helped.”

After college, Floyd became a teacher. Eventually she returned to her old neighborhood to work at Weequahic High School.

Housed in a 1930s Art Deco building, Weequahic is one of Newark’s most storied schools. The writer Philip Roth, who depicted Newark in his novels, graduated from Weequahic in 1950. In 1963, it earned the distinction of having more alumni with Ph.D’s than any other New Jersey high school.

At the time, the surrounding neighborhood, also called Weequahic, was home mostly to Jewish families. But after Newark’s 1967 unrest, when Black residents protested decades of police brutality and government neglect, white residents fled to the suburbs and middle-class Black families settled in Weequahic.

The high school remained a proud institution, where New Jersey’s lieutenant governor, Sheila Oliver, was a student and Newark’s mayor, Ras Baraka, was vice principal. Today, it boasts a celebrated marching band, popular Black history classes, and an active alumni association.

But the disinvestment that followed Newark’s white flight left Weequahic’s residents with fewer resources and opportunities. Pre-pandemic, more than 30% of children in the area lived below the poverty line, a rate twice the statewide average. The challenges seep into Weequahic High School, where only a third of graduates in the class of 2019 enrolled in college — the lowest rate in the city.

After Floyd arrived at the school five years ago, she quickly developed a rapport with her students. They would stop by her classroom for lunchtime tutoring, then confide in her problems they were having with family and friends.

Bashir Muhammad Akinyele, a longtime Weequahic teacher, said students see in Floyd a Black woman who has excelled despite the racism that she and her students endure.

“She grew up in Newark in some of the toughest neighborhoods and became a great educator,” he said. “The kids really admire that, they respect that.”

Floyd was teaching 11th grade English last year when the Newark school district announced on March 13 that it was temporarily closing school buildings due to the escalating coronavirus outbreak. The rest of New Jersey and the country soon followed.

Floyd had hoped the temporary shutdown would give her time to grieve the loss of her ex-husband, whom she met as a teenager and remained close with until his death that February. (The official cause was “respiratory complications,” which Floyd now believes might have been due to COVID-19.) However, concern for her students soon consumed her.

Some could not get online. Others took on jobs to help pay the bills, including one of Floyd’s students who started working full time at her family’s bodega. Other students worried the virus would find their loved ones — a nightmare that came true for one student who lost the grandfather who had raised her. Still others clashed with family members during the indefinite lockdown, including a student who was kicked out of her home despite being pregnant.

“School was their escape,” Floyd said last April. “Now, it’s like they’re trapped.”

She tried everything she could think of to reach her students. She had her teenage son contact some through social media, stopped by the bodega where one worked, and spent hours at a time calling all 94 of her students. Still, some she couldn’t track down. It was as if they had vanished.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus ravaged Newark. Inadequate health care, multigenerational households, and essential jobs outside the home had left many residents — 86% of whom are Black or Hispanic — especially vulnerable to the virus. When the first wave peaked in April, Newark averaged 200 to 300 new cases and dozens of deaths each day.

The city sprung into action. The district loaned out laptops and school employees set up food distributions. Mayor Baraka tried to educate the public about the virus and took steps to limit its spread, while the city health department coordinated a sophisticated system for identifying and isolating infected people. By June, the share of COVID-19 tests that came back positive had dropped to under 10% — down from nearly 70% on April 5 — and daily new cases plummeted from the hundreds to the 20s.

Despite the strange new distance between them, Floyd and most of her students made it to the end of the school year. That June, she texted a student to praise her hard work. The young woman replied that she couldn’t have done it without her teacher.

“No,” Floyd texted back, “we did it together.”

Not yet normal

This school year was supposed to begin the return to something like normal.

Instead, many districts, including Newark, repeatedly delayed reopening classrooms as the pandemic’s second wave erupted. Yet the prolonged closures were not spread evenly. In New Jersey and nationwide, Black and Hispanic students have been far more likely than white students to continue attending school remotely.

Floyd felt that was for the best. While she longed to hug her students, she feared bringing the virus home to her children. Already, she had seen it claim the lives of several district employees and so many others in her community.

“I want the dying to stop,” she said in August.

Remote learning is much improved this school year. But that hasn’t solved the problem of students not showing up to class. This fall, more than 1 in 5 Newark students were chronically absent — a figure that does not include students who miss virtual class but submit work, which the district counts as present.

With more businesses reopened, Floyd had students who worked at the mall, the movie theater, fast food restaurants, and the laundromat by her house. Others still had internet issues, while some were fed up with online learning. On most days, only about half of her students attended her video classes.

Floyd decided to give those missing students a nudge. Each morning, she called one oversleeper to say, “Get up, let’s go!” She visited McDonald’s during a parent’s shift to discuss her son’s attendance. She started walking to missing students’ homes since she had gotten rid of her car the year before. During a winter storm that shut down the state, she took her daughter on a snowy hike to find a student who hadn’t been doing his work. She figured it was the perfect time to catch his family at home.

“Students need to know — more so now than ever before — that people care,” Floyd said. “Once I started knocking on their doors, they were like, ‘Wow, you really care.’”

A few months ago, one of Floyd’s students and her family had to temporarily move into a hotel after a fire destroyed their home. The student had lost most of her possessions, including the laptop she used for school, so Floyd told the student to borrow hers.

“That was a great feeling,” said the student, Tanira Roberts. “I feel like she really cares for me, and I really care for her.”

Mirabel Chukwuma is one of the students who appears on Floyd’s screen each day, ready for class. She is a driven freshman who plans to become a pediatrician and had looked forward to meeting “mature people” in high school. When Floyd said early in the school year that she likes when students ask lots of questions, Chukwuma said to herself, “Oh, we’re going to be friends.”

Still, staying motivated after a year of remote school has been a challenge even for her. She’s texted her cousin for advice and searched YouTube for inspirational videos; she likes ones that show how to organize your binder. But it’s Floyd, and the encouragement and affection she showers on her students, that motivates Chukwuma the most.

“She’s the main reason that I want to go to class,” the ninth grader said. Last month, on Floyd’s birthday, she texted her teacher to say thanks for being “an amazing, strong, funny, uplifting person.”

“She is a strong woman,” Chukwuma explained, “and that’s what I like about her, because strong women are able to do a whole lot of things.”

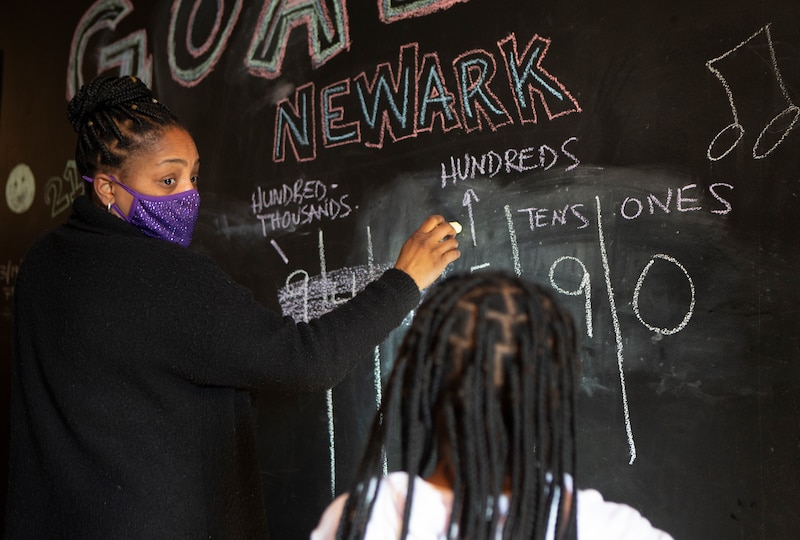

After Floyd’s morning lesson last week, she video chatted with students. One ninth grader had been turning in his work but hadn’t attended a single virtual class before that day. Another student was falling behind; she told him, only half joking, that she would come to his house if she had to. In between classes, she checked on her son and taught her daughter a quick math lesson on a giant chalkboard in the kitchen.

By day’s end, she was exhausted. But she had decided that, no matter what came next, she would keep going — for her students, her city, and herself.

“Now I’m really walking in that,” she said recently. “I’m going to stay strong.”

Erica Seryhm Lee contributed reporting.