On the day before spring break, the lobby of Roseville Community Charter School overflowed with food.

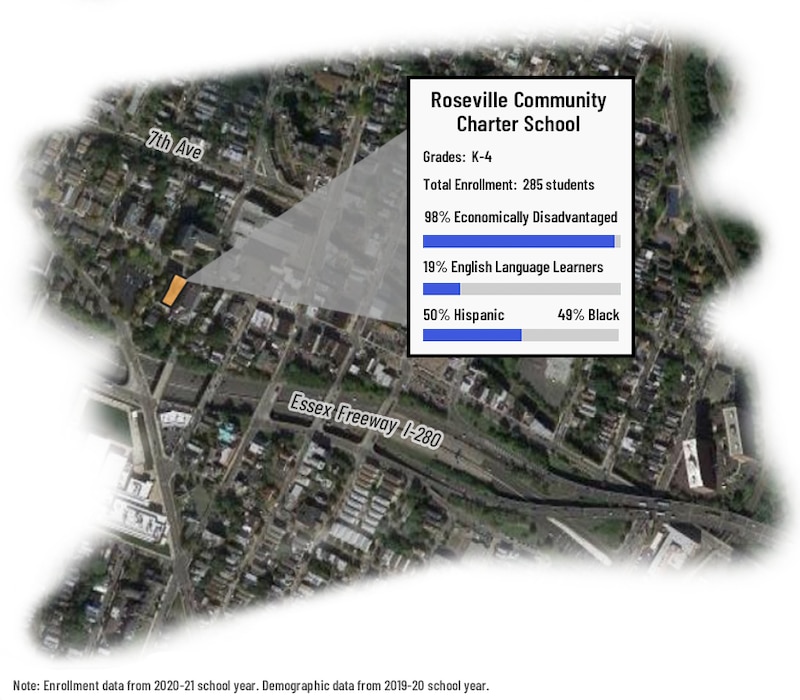

The April vacation meant families would go more than a week without support from the Newark, New Jersey, elementary school, where 98% of students are economically disadvantaged. So staffers in masks and gloves stood at the school entrance that afternoon handing out bags stuffed with donated cereal, pasta, popcorn, and canned vegetables.

When a family who had recently suffered a house fire arrived, Dr. Dionne Ledford, the school’s principal and executive director, pulled them aside. She handed the third-grader and her mother Walmart gift cards worth $1,100, which school employees had raised to help the family recover.

A few minutes later, Maranda Morinia came to pick up music supplies for her fourth-grade daughter, Brooklyn. In between shifts at a daycare center and Amazon’s grocery service, Morinia caught glimpses of Brooklyn’s virtual classes and was impressed. “You guys are doing amazing,” she told the principal.

“We’re trying,” said Ledford, a 32-year veteran educator who began her career teaching Newark children with behavioral difficulties. “We always say: We can’t do it without you guys.”

At Roseville, and schools everywhere, the pandemic has toppled the walls separating school and home. Families and educators developed a new intimacy as they peered virtually into each other’s living rooms and overheard each other’s conversations. And as both sides labored to keep children learning, they leaned heavily on one another.

In Newark and beyond, parents dealing with lost jobs, precarious housing, and sick loved ones looked to schools for help with food, counseling, and childcare. And teachers counted on parents and guardians to connect students to online classes and enforce classroom rules at home.

“You couldn’t navigate this school year without parent partnership,” said Paula White, a former Newark school leader who heads Educators for Excellence-New York. “In this moment, it’s a nonstarter if you’re not engaging parents.”

Roseville educators shepherded students through challenges small and great — from spotty Wi-Fi to the death of a parent. And most families kept children coming to virtual class, even when that meant logging on from cars, workplaces, or different countries.

Whether these family-school partnerships will outlast the pandemic is an open question, one that will soon be put to the test. As the post-COVID recovery begins, schools like Roseville will need to enlist families in efforts to shore up students’ learning and mental health. And, most urgently, schools must persuade still-wary families that it’s safe to fully reopen classrooms this fall.

“The only way they’re going to respond to that,” White said, “is if they trust the messenger.”

A community in crisis comes together

When the coronavirus sent the world into lockdown last spring, Roseville was in better shape than many schools: It had laptops on hand to send home with each of its nearly 300 students. Yet the technology would do little good without parents like the Dairos.

Oyefunmilola Dairo is a certified nursing assistant at a hospital in Elizabeth, and her husband, John, works at a Papa John’s Pizza distribution center. The couple, who emigrated from Nigeria several years ago, coordinated their shifts so that one parent was always with their daughter, Abigail. Though she ended her kindergarten year learning from a laptop in her bedroom rather than a Roseville classroom, Abigail’s parents made sure she never missed a day of class.

“We just figured out a way,” Oyefunmilola said, “and somehow it worked for us.”

As New Jersey became an epicenter of the pandemic last year, COVID-19 patients thronged the hospital where Abigail’s mother worked. The Dairo family remained healthy, but many other Newark residents were not so fortunate.

The city’s mostly Black and Hispanic populace was especially vulnerable to the virus. Many had preexisting medical conditions, such as asthma, or held jobs at nursing homes, warehouses, and grocery stores where working remotely was not an option. In April 2020, nearly 60% of the roughly 8,000 coronavirus tests administered in Newark came back positive. By this June, nearly 360 out of every 100,000 Newark residents had died from COVID — twice the national average.

Late last summer, a rising tide of COVID cases forced the city’s schools, including Roseville, to scrap their reopening plans and begin the year virtually.

That was painful news for the Dairos. Not only was Abigail entering first grade, but their four-year-old son, Michael, was starting preschool. On top of everything else, Oyefunmilola was pregnant. Yet the parents had no choice but to keep working.

John would pull the night shift, sleep for a few hours, and log Abigail on to school by 8 a.m. Oyefunmilola, who clocked in at the hospital before sunrise, returned home each day around 4 p.m. By then, John would be waiting in his car, ready to return to work.

“As soon as she drives in,” he said, “I drive out.”

Despite their grueling schedules, the Dairos felt blessed. They were not among the thousands of Newark residents who lost their jobs last year when the pandemic paralyzed the economy. The city’s unemployment rate skyrocketed from 6% in 2019 to over 22% last June. Compounding the misery, unemployment offices were closed and online systems were backlogged; even federal food benefits were delayed. Many families turned to food pantries.

“I’ve never seen bread lines that long in the 20 years that I’ve worked here,” said Catherine Wilson, president and CEO of United Way of Greater Newark, which established an emergency relief fund.

Roseville, which serves grades K-4 in a former Catholic school building in northwest Newark, tried to do all it could to help students and their families weather the storm.

Last fall, school officials brought students with disabilities into the building to receive in-person services. After Ledford heard how some working parents were struggling with childcare — including a postal worker who had to detour from her delivery route to check on her child — Roseville allowed the children of essential workers to learn in person, too. (The arrangement lasted until mid-November, when a student and staffer in the building contracted COVID and the school went fully remote.)

During video classes, teachers noticed some families’ cramped living spaces, so the school purchased laptop trays and noise-cancelling headphones for every student. Ledford also insisted that community-building events continue online. The school offered virtual workshops on parenting, technology, and financial literacy. Students and their families gathered on Zoom for holiday concerts, read-a-thons, and school-wide assemblies where cheerleaders waved their pom poms on screen.

“What we’ve learned is the importance of connections,” Ledford said. “Nothing can replace that.”

Parents also were doing their part to keep children connected to school. Even as they dropped their kids off with babysitting relatives, drove them to doctors’ appointments, or, in a few cases, left the country to stay with family members in the Dominican Republic, they still made sure their children logged in to class.

“Even if scholars were in the car riding with their parents, they still were able to be in school,” said Morinia, the fourth grade parent. “Nobody’s missing any days.”

Recognizing those efforts, Roseville tried to lighten the load on families. Molisa Cheng, Abigail’s first-grade teacher, promised parents this fall that she would teach their children to become self-sufficient.

“Now she does everything by herself,” Oyefunmilola said about Abigail. “My God, I don’t know how they did it.”

A partial return

By late April, Roseville’s classrooms were stirring to life.

After 13 months of remote learning, most students started returning to school two days a week. (About a third of students remained fully virtual.) Ledford was delighted. Everyone was following the new safety protocols. And despite some initial apprehension, teachers and students seemed at ease and excited to be back. Parents were thrilled, too.

“I’m tired of them being in the house!” Charlene Bowman told Ledford as she dropped her daughter off at school on April 20, during students’ second week back.

Inside the school that morning, hybrid learning was going smoothly — even if it only loosely resembled pre-pandemic school.

In a first-grade classroom, Molisa Cheng was teaching a reading lesson about the “magic” silent E to her online and in-person students. The four students in the classroom sat behind plastic shields at desks spread far apart. Instead of looking at the flesh-and-blood Cheng, they watched her on laptops and listened through thick headphones. During independent work, the only sound was the hum of the newly purchased air purifier.

Abigail had started coming into school Mondays and Wednesdays, but it was a Tuesday so she was at home. After the lesson, she piped up on Zoom to compliment a classmate.

“And,” she told Cheng, “I want to give a shout-out to you for teaching us.”

The return to classrooms did require adjustments. No longer could students pet their dogs, chase their siblings, or grab a snack whenever they wanted. “At home, they eat all day,” Cheng said, as a girl in the classroom pulled out a sandwich for the 10:30 a.m. snack break.

In COVID-era school, students could no longer work in groups or switch classrooms. Now, they ate lunch at their desks and took art and physical education through Zoom. Simply interacting in person took some relearning. “It was almost like they had muted themselves,” Ledford said.

The changes didn’t bother students like Abigail, who treasured her two days per week in the classroom. Each evening, she asked her parents if the following day was her turn to attend “real school.”

“It’s my very, very favorite part,” she said.

About half of Roseville’s students are Hispanic and just under half are Black. Their year away from physical school was part of a nationwide trend, in which Black and Hispanic students were far more likely than white students to remain at home even as classrooms started to reopen. Those students have also experienced the biggest learning gaps over the past year.

Meanwhile, many young people have struggled with anxiety, isolation, depression, and other mental health challenges during the pandemic. But low-income Black and Hispanic children were at a heightened risk for such struggles, experts say, because they were more likely to endure potentially traumatic experiences, such as a loved one falling ill or a parent losing a job.

“For these kids, it’s really cumulative stress that is causing them difficulties,” said Dr. Mark Kitzie, executive director of the Youth Development Clinic of New Jersey, which provides mental health services to Newark youth. “It’s kind of like a pot of water that’s just about boiling and you turn up the heat.”

Roseville has tried to foster mental wellness over the past year with virtual yoga classes and lessons on social-emotional skills, such as self-regulation. The school also provided counseling to students who needed it. Among them was a first grader who, right around Christmas, lost his father to COVID-19.

For some students, the healing process started when they returned to school. In-person classes offered a reprieve from crowded homes and unreliable internet and delivered a twice-weekly dose of consistency and calm.

Learning at home “was kind of hard because I had some internet problems,” said a fourth-grader named Erick as he stood in the bright hallway outside his classroom. “I had to take care of my little brothers when my mom wasn’t there.” For him, returning to school was a relief.

“I get to see my friends and teachers,” he said, “and I get to do my work without being distracted.”

Michael Stokes Jr., the fourth-grade math teacher, found that many of his students focused more and progressed faster in the classroom. Those who’d been silent on Zoom seemed to emerge from their shells in person.

“I’d be like, ‘Wait, is this the same student we had online?’” he said.

Still, Stokes knew there was a limit to how much ground students could make up during two months of part-time in-person learning. And that didn’t include the roughly 30% of Roseville students who’d stayed fully remote.

“I think when it comes to next school year, there’s going to be a lot of challenges,” he said, referring to schools generally. “They’re going to have to figure out: How do we get these students caught up?”

Preparing for what comes next

By the end of May, Roseville had started looking ahead to next school year.

After lunch one afternoon, Cheng asked her students to share goals they had written for second grade. In the classroom, one student said she would learn to count to 100; another said she would make new friends. Over Zoom, Abigail said, “I’m going to do anything to get as smart as I can.”

Then Cheng called individual students to a side table, where she sat behind a clear divider like a bank teller. As students read passages, she assessed their reading skills. “I think you’re ready for second grade!” she told one girl. Like Stokes, she noticed the in-person students pulling ahead.

Cheng continued to rely on parents to keep the remote students on track. Parents texted or emailed Cheng their children’s work, and Cheng reached out when their children wandered off screen.

“We couldn’t do it without the parents,” she said.

It wasn’t just Roseville thinking about the fall. Last month, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy said all students must return to classrooms full-time next school year. Schools would receive billions of additional federal dollars to aid in their recovery, with 20% of the money meant to fill learning gaps.

They had their work cut out for them. A recent state analysis of test scores from this school year found that more than half of Black and Hispanic students were below grade level in math and English, compared with less than 30% of white students. At Roseville, just 27% of third and fourth graders scored at or above the national average in English on a test called NWEA MAP this winter, up from 24% in the fall.

Ledford was busy planning programs for the summer and next fall to help students catch up, along with training to help teachers spot students struggling with their mental health. She felt ready to welcome every student back into the building, but knew some parents who’d kept their children home this spring were still afraid. They had some reason for concern: Just 44% of Newark adults were fully vaccinated by June 11, compared with 65% of adults statewide.

So, Ledford decided, she would keep holding meetings to discuss safety plans for the fall and would answer any and every question that families might have.

“When people trust you,” she said, “they’re more inclined to be there when you need them.”

In early June, Roseville hosted the “Funlympics” in the school parking lot. Despite the 90-degree heat, students played hopscotch and ring toss while Kidz Bop songs blared. As Cheng’s students raced while balancing plastic eggs on spoons, Ledford called out, “Slow and steady!” Apart from the masks, it looked like any other end-of-year celebration.

After the games, Cheng misted her students with a spray bottle and watched them dance. A few days earlier, she’d been reflecting on how they’d made it through this extraordinary year. She decided that without her relationships with students and their families, “nothing would be successful.”

“I do hope that even when things go back to normal, we don’t drop the community,” she said. “When you have that community, parents will do anything for you, and teachers will do anything for them.”

A few parents came to watch the festivity. Jose Cabrera, who’d kept his son remote, said he still was “iffy” about in-person learning next fall. But he trusted the school. “As long as the kids are safe, I’m with it,” he said.

Another parent, Stephanie Miranda, had initially been nervous when she sent her son and daughter back into school this spring. Then she saw them start to flourish. “They’re learning a lot more than they were in the house,” she said. Nearby, her first-grader, Eivelyn, picked up a piece of chalk and scrawled “Best Day Ever” on the pavement. Below that, she drew a heart.

Chalkbeat produced this Pandemic 360 series in partnership with Univision 41.