On a rainy and humid morning in June, 10-year-old Brandy and her younger brother, Noel, sat at separate couches in their living room, dressed in their dark-green Roseville Community Charter School uniform shirts.

Chromebooks were opened on their laps, the sounds of their teachers’ and classmates’ voices pouring out. As if vying to be the loudest, their three parakeets — Colores, Señorita, and Sorpresa — were busy nearby, chirping and fluttering about in a white birdcage. Every so often, Brandy or Noel would unmute their device and answer a teacher’s question.

The scene during the last week of school was organized and relaxed, albeit cacophonous at times — a far cry from the early days of virtual learning 15 months ago for the Newark family of five.

“Well, that was literally chaos,” said their mother, Patricia Coyotecatl, recalling the first weeks of remote instruction last spring.

After falling ill with COVID-19 and isolating indoors with her children for weeks, Coyotecatl says the “support, patience, and compassion” from Roseville charter school teachers helped ease her children’s anxieties and fears. Her family’s experience exemplifies how Roseville educators guided students and their parents that spring as families navigated virtual learning while grappling with illness, unreliable Internet access, and other obstacles.

“It was as if they were in the ocean when suddenly this powerful wave was coming at them, so you had to run and grab your kids and hug them tight,” she said. “In my house, what this pandemic primarily did was affect us emotionally.”

‘A completely hopeless situation’

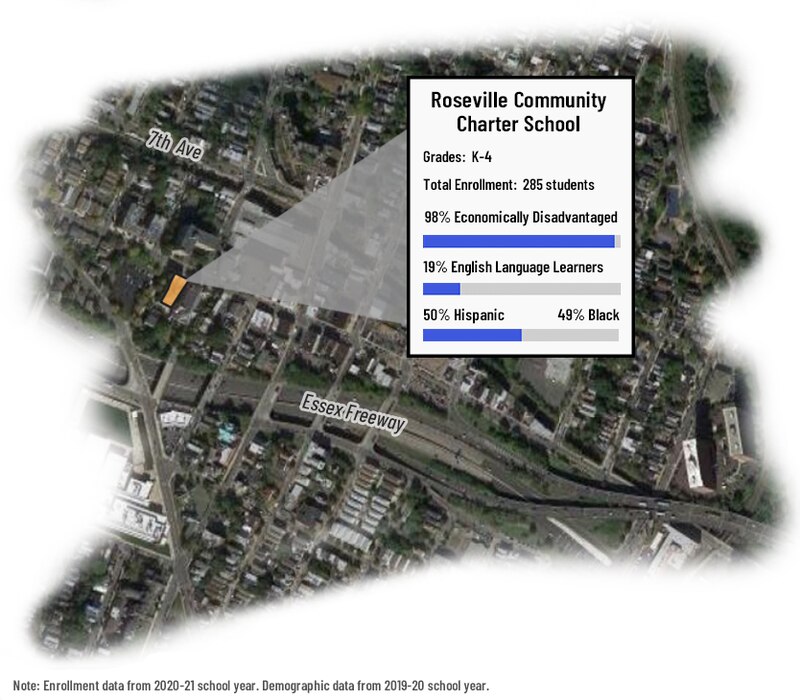

Coyotecatl’s family lives in the Roseville neighborhood of northwest Newark, on a quiet street of multi-family homes. About three blocks south stands the K-4 charter school, where her two eldest children have been enrolled since kindergarten; and about three blocks north is the Early Head Start program that her 4-year-old, Evelyn, has attended since she was six months old.

Coyotecatl, 46, migrated from Mexico 17 years ago and met her husband, Rosendo, in New York. She speaks limited English and primarily uses Spanish at home with her kids. At school, they’re enrolled in an English Language Learners program.

In March of 2020, school buildings and early childhood education centers across the state were forced to close in an effort to keep the virus from spreading.

In myriad ways, the virus disproportionately impacted Newark and its predominantly Black and Hispanic residents.

Overall, there have been 36,958 total positive cases in Newark. That translates to roughly 1 in 7.5 Newark residents who have tested positive for the virus, compared to 1 in 9 residents statewide. In terms of loss, nearly 360 out of every 100,000 Newark residents have died from COVID — twice the national average.

With a workforce largely employed at essential businesses, from nursing homes to grocery stores, and as north Jersey’s hub of transportation, the city became an epicenter for the virus early on.

And Coyotecatl, who earns money as a babysitter and from selling jewelry and cosmetics for direct sales companies, was one of the many residents who got infected with the virus in those early days of quarantine.

“It was a completely hopeless situation,” she said, recalling the symptoms she began feeling just days after her kids were told they would no longer be able to go to their brick-and-mortar schools.

For weeks, Coyotecatl had a fever, persistent cough, extreme fatigue, and lost her sense of taste and smell, she said. She also developed a relentless rash on her feet, hands, and forearms, but was never able to determine the cause, she said.

“I never went to the doctor or hospital because I don’t have insurance or money for that,” Coyotecatl said. “When it got really terrible, I would say, ‘Lord, what is happening to me?’ ”

Through phone calls with friends and letters sent home from her children’s schools written in Spanish, Coyotecatl learned more about the virus. Friends shared with her various home remedies. She said she drank herbal teas, adding lemon and peeled garlic to some, and over-the-counter medication to suppress her cough. After three weeks, some symptoms began to subside. It would take two months before she felt completely better.

During that time, she and her kids stayed home while her husband continued working as a food prepper for a New York City restaurant and helped with grocery runs when she felt too sick to go out. Noel, 9, initially would help his parents by taking out the garbage but even that became too dangerous during the peak of the first wave.

“The people that lived in the basement had the virus and the family on the second floor had it as well,” she said. “We didn’t even let the kids go near the door. They were in those four walls and with just their computers for months.”

And they feared the unknown.

“I was really scared because I didn’t know if it was really bad or if there was a cure,” said Noel, who completed the third grade this month. “It scared me a lot when my mom got sick because I heard that a lot of people were dying from the virus.”

Learning how to ‘Zoom’

On top of their fears about the virus, the family also struggled to adjust to remote learning. Before the pandemic, Coyotecatl’s family didn’t have Internet access in their apartment. After remote classes started, they were told they’d need it to keep the kids learning. Coyotecatl signed up for the most affordable service she could find, but the WiFi connection continues to be weak when multiple devices are trying to access live instruction at the same time.

“It was learning how to put them on Zoom, and learning how to check their computers and how to use Google Classroom, and make sure they have the right link and ID, and how to send an email,” she said of the early remote schooling days when she was helping her kids while battling fatigue and other COVID symptoms.

All day long, Coyotecatl recalled, she would hear the same thing:

“Mami, mira, la computadora no está funcionando.”

“Mami, ahora que hago?”

“Mami, la maestra dice que no me escucha bien.”

The computer’s not working. What do I do now? The teacher can’t hear me.

It was exhausting.

Studies over the last year have shown how the pandemic has dramatically affected working mothers, from struggling with a “double shift” of household responsibilities to mental health challenges and concerns about higher rates of unemployment, especially among mothers of color.

“Latina moms are 1.6 times more likely than white mothers to be responsible for all childcare and housework, and Black mothers are twice as likely to be handling these duties for their families,” according to a McKinsey and Company analysis published in May.

‘In this together’

For Coyotecatl’s kids, Roseville teachers were a lifeline.

“I can’t tell you how many times I had to say, ‘I’m sorry, but we couldn’t find the link.’ They would say, ‘There’s no problem, we’re all in this together right now,’ ” Coyotecatl said.

She added that the teachers would explain to her in Spanish what she couldn’t understand in English.

After more than a year under a fully remote instruction model, Roseville began holding in-person classes for students in April. Students were split into two cohorts. Through the last day of school on June 18, students were able to go in-person twice a week.

Dr. Dionne Ledford, the school principal and executive director, said the school’s partnership with parents was essential to keeping students on track over the last 15 months.

“We always say: We can’t do it without you guys,” she said, referring to the parents.

Though some parents have been hesitant to let their kids return to in-person lessons — about a third of students have remained fully virtual – others, like Coyotecatl, were eager to see some return to “a new normal.”

Since April, her third- and fourth-graders have been going to school in person twice a week and doing online classes from home the other three days. Her youngest attends an early childhood learning center Monday through Friday.

“It’s better for them to be in school in terms of physical activity, and emotional and academic support,” she said.

She hopes the holistic support her children received during the pandemic, such as social-emotional learning classes and after-school tutoring, deepens in the upcoming academic year when schools statewide return to fully in-person instruction.

Noel also prefers to be in school, he said.

“In virtual classes, I sometimes get distracted during class or the Internet stops working and drops me from the class,” he said in Spanish. “In person, the teachers can just explain the assignment, with or without the Internet. And I like that there are a lot more activities we can do that we can’t do at home.”

When looking back over the last year, Coyotecatl said the only silver lining was all that she and the family learned about technology and education.

“This pandemic was hard and there’s so much sadness that it left us, but it also left us with many lessons,” she said. “We know a little bit more about computers, about Google Classroom, about what our children are learning, and how to respond to a teacher via email. It was by force, but I feel that turned out to be one of the better parts of this experience.”

Noel had more important things on his mind. Like how tough fourth grade will be. And what’s next for this summer.

“I’m a little nervous because I don’t know if it’s going to be very hard, but first, this summer we’re planning to go to the beach,” he said. “That’s better than last summer and I’m happy about that.”

Chalkbeat produced this Pandemic 360 series in partnership with Univision 41.