My parents’ commitment to a better future saved me from a life of poverty and oppression – and led me to journalism.

My dad was a curly-haired boy and my mom was a curly-haired girl who met in their homeland of Nicaragua as the country’s revolution unfolded and extreme poverty was the way of life. They were in grade school and quickly fell in love, bonding over their drive to be the best in school.

Their love flourished during their teenage years and grew even stronger as my mom dealt with the passing of my grandma. By the late 1980s, Nicaragua’s revolutionary war was flaring and my dad had to choose between leaving the country or being drafted into the military.

They fled to Guatemala. The young couple was then in their early 20s, and in the coming months, would soon learn they were expecting a baby. My dad knew the only option to provide for his family was to get to the United States.

So, he crossed rivers, slept in the desert, and traveled on “La Bestia,” a freight train migrants use to get from southern Mexico to the U.S. border. Once on American soil, he was able to apply for Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, for Nicaraguans at the time, which allowed my dad to stay in the country legally and bring my mom.

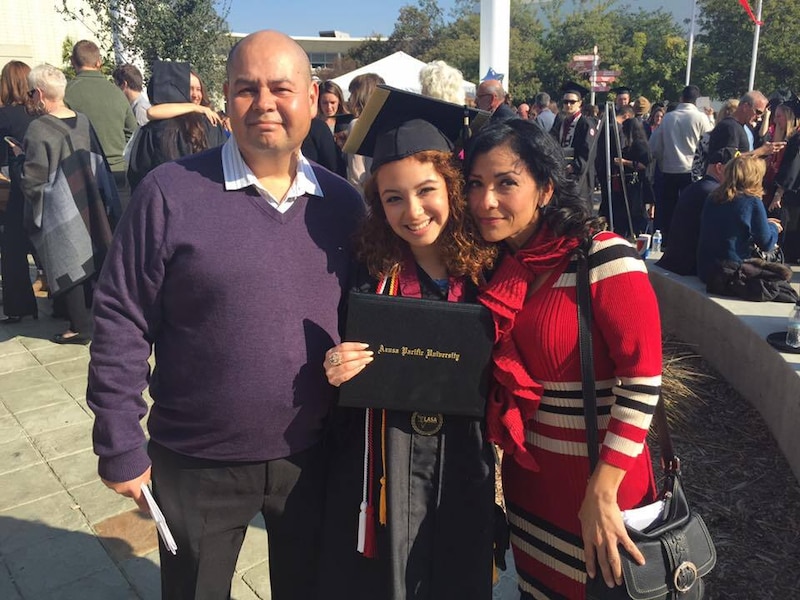

I was born in Miami, Florida in 1994 — their curly-haired daughter — and my parents were one step closer to their “American Dream.” Their sacrifices allowed me to become the first in my family to graduate college.

But as a first-generation student and later, the oldest sibling, I faced my own set of challenges as my parents were trying to understand a new country, a second language, and an unfamiliar school system.

I spent most of my elementary school years in the Jersey City Public School system before I moved with my mom to Southern California. It was a major cultural and social adjustment for me. I went from an East Coast school where the majority of my classmates came from Indian or Italian families to one in California where most of my peers identified as Mexican-American. It was hard to leave my friends, but my bicoastal experience exposed me to different communities and cultures.

My parents always dreamed that I would become a doctor or a scientist, even though I struggled with math in school. Their dream ignited my own drive to become the best student, which often meant staying an extra hour or two after school for tutoring or calling on friends for help when I didn’t understand something. Although I was an honor student in middle school and took advanced placement courses in high school, I struggled to keep up with my schoolwork while juggling my home life.

My parents’ dream inspired my own dreams

I got my first part-time job in high school to help my mom, a hairdresser and single parent at that time, support my two siblings. Just before my 16th birthday, I got my driver’s license to help drive my siblings to school and meet my mom at parent-teacher conferences, where I served as her interpreter.

I was often the secondary parent listed as my siblings’ emergency contact, and I learned to advocate for them in the school system. Between helping my mom, being a high school student, and juggling extracurricular activities and work, I was stretched thin.

Still, I managed to graduate with a 4.2 grade point average and pass advanced placement exams.

Like my parents, I was proud of all that I accomplished but staying on track to go to college was hard because my family and I were unfamiliar with the process.

We managed by asking my friends for their advice, talking to counselors and teachers, and spending countless hours googling colleges and their requirements. It was a tough journey but with the help of my parents, my educational support system, and three jobs, I graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Azusa Pacific University.

I eventually moved back to New Jersey where I got a job as a reporter at a local newspaper, covering the affluent, predominantly white suburban towns of Morris and Bergen Counties. The people and the issues they faced were nothing like my own and I often felt out of place in those communities.

Like my parents, I had moved to pursue my dreams and I was scared. But my mom always reminded me why I chose this profession in the first place: “Para ayudar a los demás.”

To help others.

At that newspaper, I reported on protests, political races, immigration, inequities, and community issues. Now, as a reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, I’m combining my personal experiences and journalism expertise to tell the stories of Newark students and help their families navigate New Jersey’s largest public school system.

It took a village to get me to college, and I am thankful for the teachers that supported me along the way and believed in me when I didn’t. I am grateful to my parents who were a constant source of encouragement in my life. Without them, I would have never developed the drive to be the best student — and person — I could be.

A fair education is the right of every child in this country. My parents gave me that opportunity by moving to a new country. Now, my goal is for my reporting to contribute to a better learning environment and experience for students in Newark Public Schools.

As we settle into the new year, I look forward to connecting with more parents, students, and teachers as I work to highlight the victories and challenges faced by students in this district.

Your story matters, and I hope you can trust me to tell it.

Jessie Gómez is a reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, covering public education in the city. Contact Jessie at jgomez@chalkbeat.org.