Sign up for Chalkbeat Newark’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

During the first week of school, temperatures soared into the 90s causing sweltering heat in some of Newark’s oldest buildings with no air conditioners and faulty water fountains.

Parents packed frozen water bottles for their children to cool off during the day while others wondered why some classrooms in New Jersey’s largest school system were unprepared to deal with high temperatures.

“No air conditioner in these schools is crazy,” wrote Jacquetta Thomas last month in a Facebook group after her grandson stained his polo shirt with blood due to a nosebleed caused by the heat. A handful of parents responded to Thomas’ post with their own concerns about hot classrooms and deteriorating conditions in city schools.

But this wasn’t the first time that Newark students dealt with uncomfortable conditions in city classrooms.

Newark’s public school buildings are among the oldest in the state, and Superintendent Roger León estimated last month that it would take more than $2 billion to fully repair and update them. The state is responsible for funding school construction projects in high-poverty districts like Newark, but a judge in a long-standing legal case said the state has not created a long-term financing plan to support the work.

In Newark’s school budget this year, 86.3% of the district’s funding comes from $1.2 billion in state aid, but that money can only fund school operations and education costs. Over the years, state officials have poured money into these projects on a “pay as you go” basis, leaving no room for long-term funding. And in comparison to wealthier school districts in the state, districts like Newark have a smaller property tax base, which limits their ability to bond for school construction projects to supplement the cost.

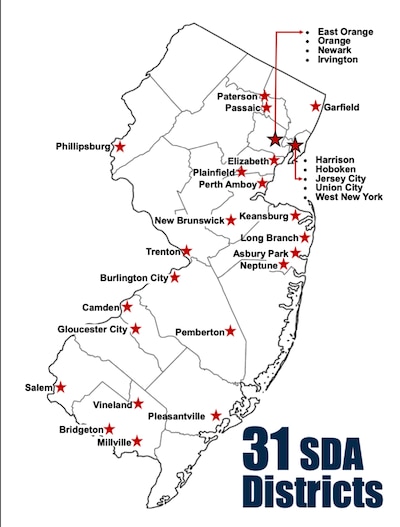

Now, the state, through the Schools Development Authority, is obligated to fully fund these projects in Newark and 30 other high-poverty districts, including East Orange, Elizabeth, and Paterson. That mandate was a result of a series of landmark decisions dating back to 1985 in the New Jersey Supreme Court case Abbott v. Burke. Those decisions ultimately helped establish the SDA. (The districts often are referred to as SDA districts.)

In 2008, the state allocated $3.9 billion in funds to the SDA, of which $2.9 billion went to high-poverty districts. That was the largest, and most recent, cash infusion to SDA before Gov. Phil Murphy unlocked nearly $2 billion over the last two budget cycles resulting in 19 new construction projects, and hundreds of building repair projects for districts across New Jersey included in the SDA’s 2022 strategic plan.

But in March, a report submitted by the judge to the New Jersey Supreme Court said the state isn’t doing enough to prove that it will keep funding the SDA and school construction projects. Now, it’s up to Murphy’s administration and state legislature to find a way to fund them.

“There’s an enormous amount of need, and the state is just putting in a fraction of the money that [schools] need,” said Danielle Farrie, research director at Education Law Center.

State delivered nine new schools in Newark since 2006

Newark Public Schools is home to just over 39,000 students across its 63 schools. Its buildings have been crumbling for decades, and state officials have been slow to address the needs.

Dozens of those schools need new mortar and bricks, boilers, and roofs, among other needs. Over the years, parents and advocates have pressured the district to make classrooms more comfortable by installing central air conditioning systems and updating deteriorating buildings. In 2016, the district asked the state to fix more than 100 school buildings but only 11 projects were approved.

Since the state’s Schools Development Authority was established over two decades ago, more than $760 million has been spent on renovation projects in Newark, the most of any school district in New Jersey. But only nine new school projects have been finished, including Science Park High School, rebuilt in 2006, Speedway Avenue Elementary School, rebuilt in 2010, and Elliot Street Elementary School in 2016, which was the first new school built in the East Ward in 104 years.

In 2022, the SDA granted the district two new prekindergarten through eighth grade schools, along with 14 other projects across the state to address high-priority needs and overcrowding. One of those schools is the recently opened Nelson Mandela Elementary School, housed in the former University Heights Charter School building. The SDA purchased the building after the state shut down the school in 2022.

A second elementary school was promised for Newark, but district and SDA officials agreed to move forward with the construction of a new University High School building instead, said SDA spokesperson Edye Maier. The project, which is in the planning stage, is meant to alleviate overcrowding as school officials project the district’s enrollment will continue to grow as the city’s population increases.

The SDA is also working on eight other projects across all SDA districts, which consist of underground vault repairs and demolition, roof replacements, masonry repairs, and stucco repairs and replacement, according to an SDA report released during its October meeting. In Newark, Technology and University high schools, along with Cleveland and Salome Ureña elementary schools, are slated for those repairs, which are valued at roughly $7 million.

In 2022, the SDA also completed structural repairs at Shabazz High School and basement water infiltration at Roberto Clemente Elementary School. The price tag was more than $3.5 million.

The projects are part of Murphy’s cash infusion to the SDA after it authorized almost $1.85 billion for school construction and capital maintenance projects for SDA districts during the 2022 and 2023 state budget cycles. In 2021, $75 million was allocated to districts for capital maintenance and infrastructure projects. Newark received roughly $6.5 million as part of that allocation.

Yet, the funds cover a fraction of facilities improvements in SDA districts. Newark Public Schools is slated to receive more funds for school construction projects as part of the state’s 2024 budget after Murphy allocated another $75 million to the SDA. Those funds have not been disbursed yet, Maier said.

The district is also working on a new assessment of school building repairs and new schools to update its needs since 2016, León has said.

School construction funding up to the state, for now

Newark hasn’t raised its property taxes in the last three years, but school officials have warned that will be an exception rather than the norm moving forward. In recent school board meetings, León has hinted at asking taxpayers to foot the bill for school construction projects.

Through a weighted student formula created under the School Funding Reform Act, New Jersey determines how much aid to send to districts to support education and programming costs across its schools. Newark saw an increase in state aid this year, but it remains $27.7 million short of the budget recommended under the formula, said Valerie Wilson, the district’s school business administrator, during March’s budget hearing.

But state aid calculated under the formula is not meant to pay for school construction or renovation projects.

“You can’t reallocate funding away from staffing and day-to-day operations of a district to fund the facilities needs that are as severe as Newark has right now,” said Farrie from the Education Law Center.

In 2021, the Education Law Center went back to the courts to compel the state to meet its constitutional obligation to fund SDA projects. The court appointed retired Judge Thomas Miller as a special master to write an analysis of the construction projects in those districts.

In his 87-page report, Miller wrote that there is a significant remaining need in the SDA school districts but no long-term plan to fund construction projects.

“The state Supreme Court has clearly said that this is not something that school districts should be funding,” Farrie said. “Newark cannot budget its way out of this hole that SDA has created.”

Last month, in a virtual conversation with Newark Mayor Ras Baraka, León said he would need to meet with city and state officials “to really figure out how to grapple and attack” the needs before presenting a bond to city residents. But that solution might not be feasible in Newark.

Wealthier school districts, which have a strong property tax base, often can support a bond for school construction projects, but a city with a smaller property tax base, like Newark, might not have that option.

Newark Public Schools’ operations are supplemented by $138.3 million from local property taxes, or 10.3% of the district’s 2023-24 budget. That number has remained the same for the last three years because Newark taxpayers haven’t seen an increase in their property taxes.

So far, there has been no mention of a bond on the November ballot.

Jessie Gómez is a reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, covering public education in the city. Contact Jessie at jgomez@chalkbeat.org.