Newark families of children with autism may have to travel outside the city to receive care or wait months to receive a diagnosis from a medical professional, as the number of diagnosed cases in the city has surged since 2000.

Researchers at Rutgers University found that as of 2020, 1 in 20 Newark children had been diagnosed with autism, compared with 1 in 167 in 2000.

Statewide, they found, autism rates among 8-year-olds without intellectual disabilities spiked by 500% from 2000 to 2016, and overcall cases among children with intellectual disabilities tripled during the same period.

The study also found disparities in the diagnosis of Black and Latino children, specifically in socially disadvantaged areas like Newark where more services and early intervention programs are needed to treat the disorder effectively.

Researchers said that while autism is becoming more common in New Jersey, the big spikes that showed up in their study were largely due to autism going under-detected in the past among children with average or above-average intellect. They said the data reflected greater awareness of autism, and pointed to the need for better screening and more autism research and services in Newark.

“Until we discover the causes and risk factors for autism, the best thing that we could do is identify the kids who have it as soon as possible and get them into interventions properly,” said co-author Walter Zahorodny, director of the New Jersey Autism Study, a monitoring system set up by Rutgers.

Zahorodny and co-author Josephine Shenouda, an adjunct professor at Rutgers, used biannual data from the New Jersey Autism Study to look at the prevalence of autism among 8-year-olds in Essex, Hudson, Ocean, and Union counties, including patterns based on family wealth and race. By age 8, experts say, most children on the autism spectrum have had a chance to be evaluated by more than one professional.

The study found spikes in all four counties. Amid that surge, children in high income areas were more likely to be diagnosed than those in lower income areas, according to the autism study. Specifically, those living in affluent areas were 80% more likely to be identified with autism and no intellectual disabilities than children in underserved areas. Similarly, Black children with autism and no intellectual disabilities were 30% less likely than white children to be identified.

Half of Newark’s children identified as Black, and 43% as Latino in 2019, according to data from the 2022 Newark Kids Count. By 2018, approximately 9% of boys in Newark had an autism diagnosis, and by 2020, 2.3% of girls had one.

The researchers estimated that as of 2020, about 6% of Black children in the city had an autism diagnosis.

“There are many more children that need to be evaluated, but there’s a supply problem,” Zahorodny said, adding that there are not enough professionals with the training and experience to diagnose children.

The Rutgers team found that children from underserved communities were significantly less likely to get their first professional evaluation before 36 months of age, and therefore less likely to participate in early intervention programs.

Additionally, school districts like Newark are seeing increased demand from families of students with autism and other disabilities for speech therapy and other services. Currently, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School has just one full-time developmental pediatrician for the Newark area, according to Zahorodny.

“I’m pretty sure that none of the school districts have the right or even sufficient number of speech pathologists, physical, occupational therapists, and other experts who can help the child,” Zahorodny said.

Barriers to care in Newark

Before the pandemic shut down schools in 2020, Nyemia Young was seeking help in getting her then 2-year-old son, Nasariah, diagnosed with autism after noticing changes in his development. She remembers calling hospitals in different towns and doctors in neighboring cities for an appointment, only to be told she would have to wait up to 12 months at some locations.

Young was hoping to get Nasariah into an early intervention program, but once the pandemic hit, she had to wait another year to get a proper diagnosis.

“In order for him to get the help, I know I needed to go beyond where I was living to get it,” Young said.

Ultimately, Nasariah was diagnosed in August 2021 at a specialty hospital in the Bronx, more than 20 miles from Young’s home. Despite the distance, Young was relieved to get the diagnosis, which made her son eligible for an early intervention program five days after he turned 3.

“Then the Newark Board (of Education) reached out to me and started giving me all these questionnaires,” Young said. “That made me open my eyes, and I started looking at the different schools in Newark with autism programs.”

Young found support at Nassan’s Place, a Newark community group providing educational and recreational activities for autistic children and their families. The group helped her understand what her son was going through and recommended programs and schools for Nasariah.

Nadine Wright-Arbubakrr, president and founder of Nassan’s Place, said she hears from parents who are frustrated with the months-long wait to see a doctor and the difficulties in navigating the medical system to find help. Language barriers are also a problem for some families.

“Those who have tried to get support are being told they got to wait six to nine months,” Wright-Arbubakrr said. “That’s a valuable time frame, where the children are losing the opportunity to get the resources that will better serve them or better help them with delays.”

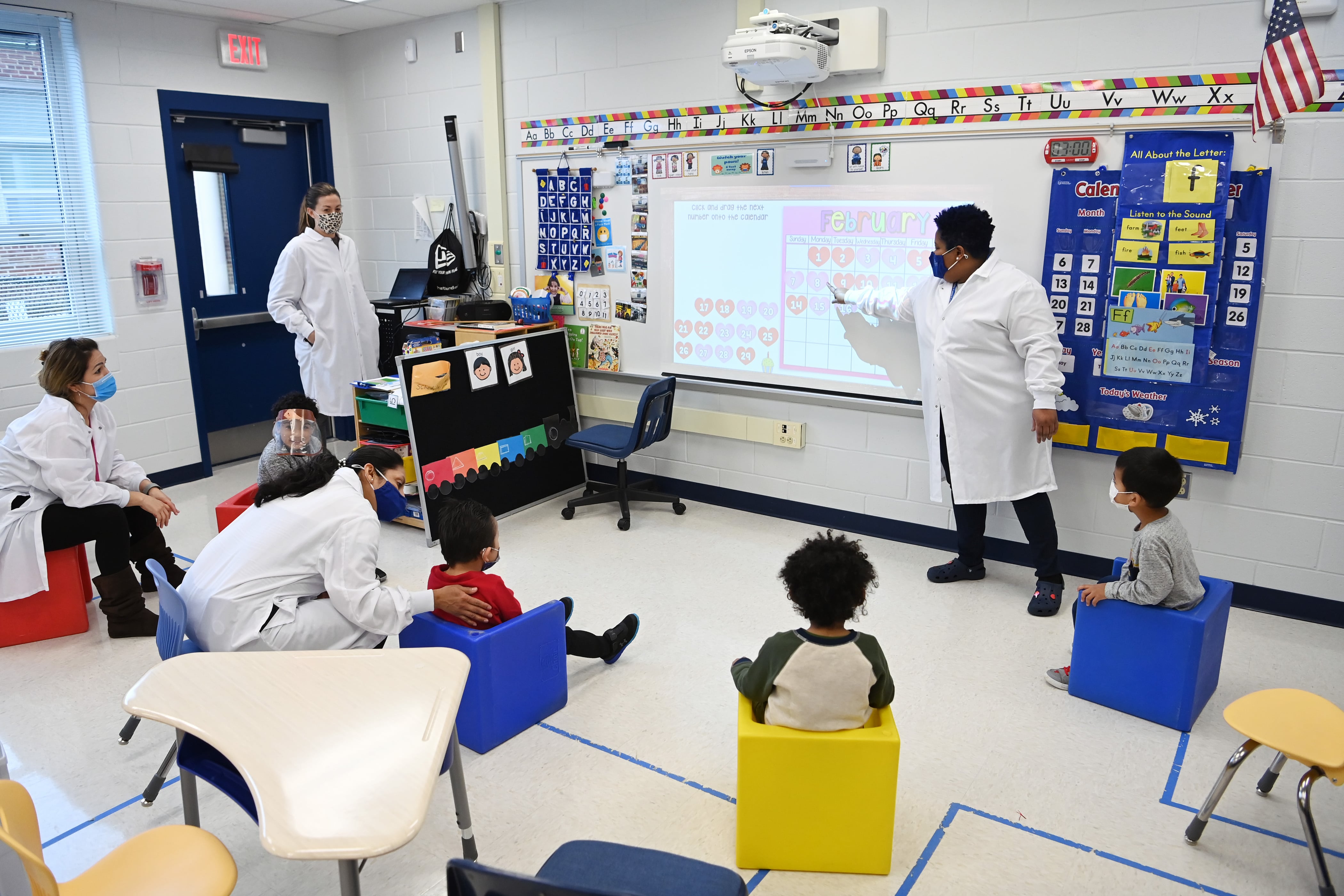

Nasariah is now in his second year at the ECC North school, where he receives speech and occupational therapy services to help with his speech delay and day-to-day tasks. Young said she felt lucky to get an early diagnosis for Nasariah but still has to drive to places outside Newark, like the Children’s Specialized Hospital in Union, where her son gets additional occupational therapy services.

This year, Newark Public Schools has 40 speech-language specialists, three occupational therapists, one physical therapist, and one audiologist working at the school level to provide related services to its more than 6,600 students with disabilities, including those with autism. The district also recruited two new outside agencies to provide additional support in occupational, physical, and speech therapy.

But Young said she feels the system is burdensome and plans to move to another state to find better support. She said she hopes the spike in autism cases in New Jersey calls attention to the needs of children like hers.

“I just want to make sure that wherever I go, they have all the things they need for Nasariah,” she said.

Jessie Gómez is a reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, covering public education in the city. Contact Jessie at jgomez@chalkbeat.org.