When Melissa De Almeida’s parents immigrated to Newark in the 1990s from Brazil, navigating the public school system for their two daughters was among their steepest battles.

De Almeida’s older sister struggled to learn English in a system where few teachers spoke her native Portuguese. By the time Melissa enrolled a few years later, she encountered teachers who were able to communicate with her family, but it was uneven.

There was, though, one shining light: De Almeida’s second grade teacher at Oliver Street School. De Almeida fondly remembers her teacher making s’mores and fresh lemonade for her class, but the big difference was that she could speak with De Almeida’s parents in Portuguese.

Now, the 19-year-old sophomore at Montclair State University wants to be a bilingual teacher and help families like hers in Newark, her hometown, where roughly 9% of students speak her native language.

“I need to be the change that my sister needed,” said De Almeida, who graduated from East Side High School last year.

In Newark and other cities in New Jersey, teaching staff and school leadership do not always reflect diverse student bodies. Demographic data shows Black and Latino students make up about 90% of Newark’s total student population, while teachers from those backgrounds make up just over half of the teaching staff.

Roughly 20% of Newark schools have a majority of white teachers. Other cities in New Jersey have even lower proportions of teachers from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds.

A close look reveals that Latino students, who are increasing in number annually in the district, are starkly underrepresented in the district’s teaching staff, a Chalkbeat analysis of 2021-22 state-provided school demographic data found.

White teachers make up a majority of the teaching staff at one in five district schools, and Black teachers are the majority teaching staff at a little more than one in four schools. But no school in the district has a majority Hispanic or Latino teaching staff — even though roughly half of all the district schools have a majority Latino student body.

One of the district’s high schools has a Latino student population of more than 61%, but no Hispanic or Latino teachers. Three other schools also don’t have any teachers who identify as Hispanic or Latino.

Similarly, the state’s population of Latino children has expanded — by roughly 25% — since 2010, but an analysis from NJ Advance Media found that roughly 30% of all schools don’t have any Hispanic teachers at all. In addition, districts have seen a growing student population identified as English language learners while also facing a shortage of bilingual teachers.

Many experts say that desegregation court rulings, which have failed time and again to wholly integrate student bodies and personnel, have contributed to the disproportionate numbers of white teachers.

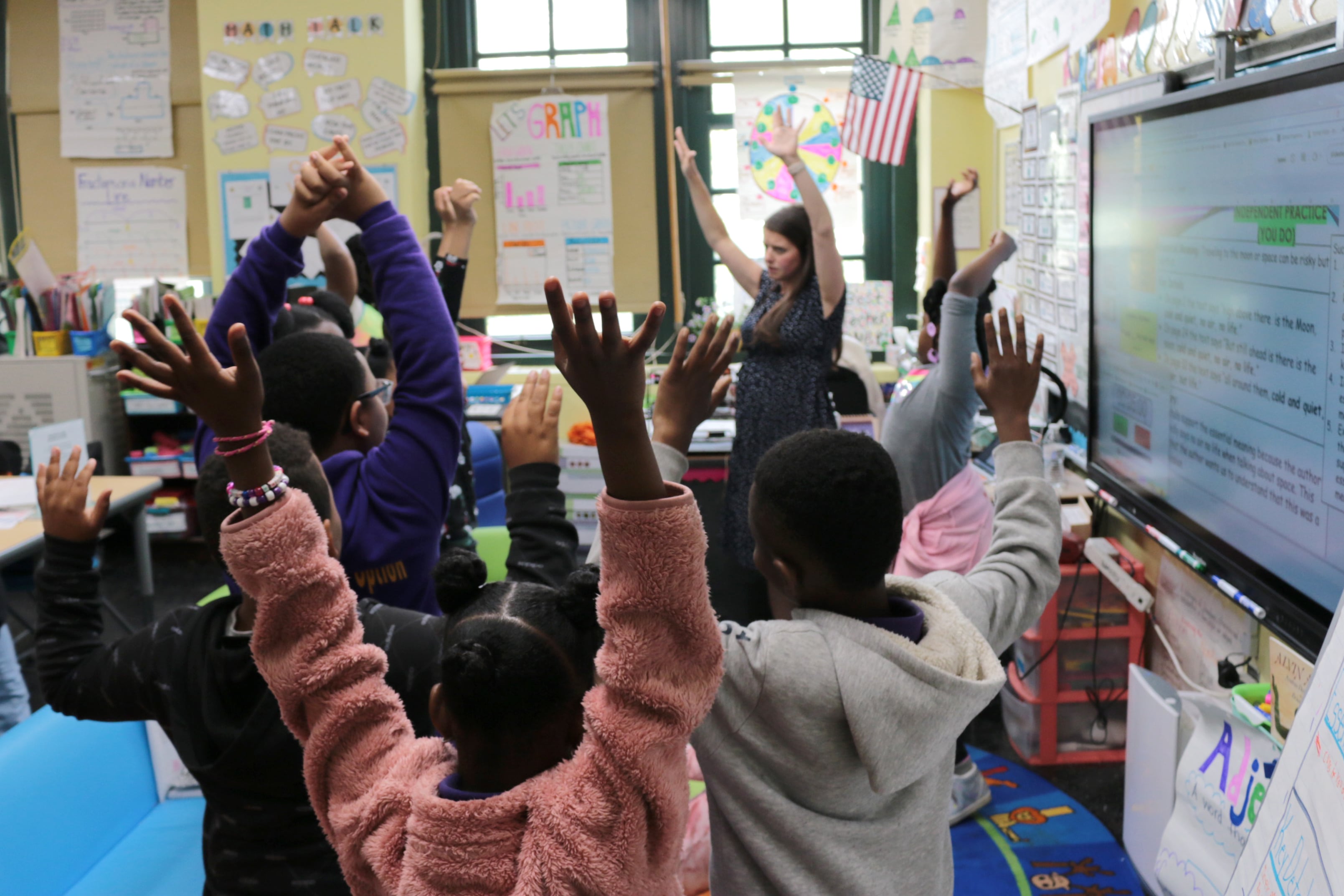

Yet, numerous studies show that a diverse teaching staff, especially one representative of a school community, can foster stronger teacher-student bonds, stronger relationships between teachers and families, and lessons that are more culturally responsive — the benefits De Almeida experienced first-hand with her second grade teacher.

Newark Public Schools’ demographic data also displays a glimmer of hope when it comes to moving closer to a teaching workforce that reflects its student body: A handful of elementary schools with majority Latino students have a notable number of Latino teachers, ranging between 33% and 44%. And Black students are more likely to have proportionate representation in administration and teaching staff, data show.

Having teachers who students from underrepresented backgrounds can identify with racially and culturally is just one component of teacher and school quality, but it can help lead to improved attendance, test scores, and the likelihood of taking an advanced course, research has found.

“If we don’t more aggressively address the demonstrated mismatch between students and the school personnel who serve them, we may not see an acceleration of academic achievement by all of our students,” said Leslie Fenwick, dean emerita at Howard University whose expertise is on teacher diversity and education equity. “We must do a better job of recruiting, retaining, and promoting teachers and principals of color.”

‘We are living with the fallout of the history’

As De Almeida’s story with her sister illustrates, many students don’t have teachers who share their background – and the gap between Hispanic or Latino students and teachers is only expected to widen, statewide and nationally, studies suggest.

Nationally, white teachers make up 80% of the teaching force, and in New Jersey, it’s 83%. Meanwhile, the state’s teaching force — also mirroring national trends — is 8% Hispanic and 6.5% Black, while those student populations are 32% and 15%, respectively.

A lawsuit before New Jersey’s Superior Court in Trenton is arguing that the state — one of the most diverse yet segregated public school systems in the country — is responsible for addressing the fact that more than half of Black and Hispanic or Latino students attend schools that are predominantly non-white. The lawsuit, led by The Latino Action Network and NAACP-NJ, argues that the state is violating its own constitution and the Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka from nearly 70 years ago.

That historic Supreme Court ruling — and several desegregation rulings that followed — declared segregated schooling to be a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. But it also led to an uneven proportion of white teachers to teachers of color as people, including those in power who upheld segregationist beliefs, resisted desegregation efforts, analyses of historic documents show.

“We are living with the fallout of the history that occurred — not as a result of the Brown [v. Board of Education] decision, but of the massive white resistance to it,” said Fenwick, who authored the book “Jim Crow’s Pink Slip: The Untold Story of Black Principal and Teacher Leadership.”

Racism and segregationist beliefs led to widespread illegal firings, dismissals, and demotions of Black teachers — upwards of 100,000 — between the 1950s and 70s, Fenwick said in a recent phone interview with Chalkbeat and described in her book.

Desegregation efforts must also invest in teacher diversity, Fenwick says. Without that, students of color will continue to lose out on the massive opportunities a teaching staff that reflects them can offer, including on a social emotional level, as well as academically and behaviorally, which decades worth of research has documented.

“Unless we address this diversity issue in the school leadership and teaching forces, I fear we won’t make the kind of progress that we need to make in the country,” Fenwick said.

Newark works to create diverse teacher pipeline

Though Black teachers make up a majority of the teaching staff in some Newark district schools, the proportion of Black teachers has dropped about 10 percentage points since the late 1990s, when the district was under state control, a 2021 analysis from New Jersey Policy Perspective found.

The district has recruitment efforts in place to attract teachers from diverse backgrounds, including one that creates a pipeline of “home grown teachers” by incentivizing current students to major in education and get a guaranteed teaching position in the district after they graduate college.

During a June press conference, Superintendent Roger León agreed that diversifying his staff “is good in that it brings about different viewpoints” and noted the district’s recruitment strategies, which include a teacher-to-principal pipeline initiative that targets Black and Latino male teachers.

The district partnered with Montclair State University’s College for Education and Engaged Learning to create the Red Hawks Rising Teacher Academy, a dual enrollment program at East Side and University high schools where students earn college credits at no cost as they prepare for a career in teaching. The program recruits students into the profession at an early age, provides mentorship, and guarantees an offer of admission to the university’s teacher education program after high school graduation.

An essential part of the program is that it encourages students to return to teach in their hometown district after college graduation.

León has promised participants that a teacher contract with the district will be waiting for them after they complete the university’s program.

De Almeida, a graduate of the program at East Side, says being part of it helped her envision a future helping students who speak different home languages. But what helped her see that she could be successful, she said, was the example set from program co-directors Mayida Zaal and Danielle Epps, women of color who are graduates of urban school districts.

“I think it’s kind of refreshing to have someone talk to you that understands and kind of has been through what you’ve been through and kind of walked that path with you,” De Almeida said.

‘Retaining teachers is the problem’

In a recent phone interview, Newark Teachers Union President John Abeigon said he supports the district’s recruiting efforts, but “retaining teachers is the problem” that León needs to address, particularly when it comes to teachers of color.

“We have white, Black, Hispanic, brown, the rainbow,” Abeigon said about the diversity of teachers in his union. “Everybody that comes to this district, a majority of them leave within a couple of weeks or months of working in this district. That’s endemic to the district and the way it treats its staff.”

Research has found that teachers of color are more likely to teach in “high needs, hard-to-staff schools with challenging work environments and higher attrition rates for all teachers,” a FutureEd report on teacher diversity stated.

As teachers from diverse backgrounds navigate districts with low resources and unfavorable working conditions, though, they often feel undervalued and overlooked, according to feedback from focus groups in a 2019 report that examined retention of teachers of color.

Nubia Lumumba, a Black and Muslim educator and former English teacher at a Newark high school, resigned from her position after just six months of working in the district. Lumumba said she experienced and witnessed racial harassment while teaching, but lack of sensitivity from school administrators in handling concerns of racial harassment led to tensions that ultimately led to her resignation.

There was a lack of “genuine empathy for what I had gone through,” Lumumba said, adding that students were witnesses to what she experienced. “If, as a mature adult, it cut me deeply to have experienced racial and religious harassment and not get any meaningful support from district and school leaders, then, I imagine, it must be even more damaging to the Black students.”

Lumumba, who taught for eight years prior to her last role, said schools need to have strategies and programs in place that will bring “a true understanding and celebration of diversity” and support students of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. This could lead to improved retention, she said.

The teachers of color in the 2019 case study would agree. Among solutions outlined in the report: District leaders need to ensure that “schools are places that culturally affirm teachers of color,” empower teachers with pathways to leadership, and offer compensation for extra work.

A New Jersey task force on school staff shortages, put together by executive order from Gov. Phil Murphy last year, released a report earlier this year that shows signs the state is paying some attention to the retention of teachers.

Providing support to schools in “implementing policies and practices that create a work environment that is free of bias, including microaggressions,” as well as increasing teacher pay and expanding “mentorship and professional development for early career educators” were among the recommendations listed in the report.

Students need support through higher education

For Red Hawks Rising co-directors Zaal and Epps, their efforts with the district to diversify the teaching force start by supporting Newark students and becoming their “community of commitment” as they navigate high school, college, and long-term careers, Epps said.

“We can’t just focus on the recruitment of young people who represent Black and brown communities, and then not be intentional about how we’re going to support them to get to the finish line,” Zaal said. “There has to be support along the way so that we don’t have a sort of leaky pipeline into schools.”

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the overall college enrollment rate among 18- to 24-year-olds decreased from 41% in 2010 to 38% in 2021. The overall college enrollment rate that year was even lower among Black students at 37% and Hispanic students at 33%.

While in the dual enrollment program, students confront different misconceptions about higher education, such as the idea that to pursue a career they have to leave their hometown or that college is financially out of reach, or the belief that “college is not something that’s for me,” Epps said.

Many students in the program are bilingual or bicultural and have experience dealing with educational challenges that, in turn, could help their future students.

“They’ve been raised in resilient families where they have been able to figure out their way into college as first-generation students,” Zaal said. “So, they have a significant amount of social capital to offer.”

De Almeida, who’s set to graduate in 2026, gives back to her community by working with parents at her local church and helping them understand their children’s homework or providing translation support for them. She relates to those families, she says, and talks to them about helping her own family financially while juggling school work and pursuing her dream of teaching.

The aspiring bilingual teacher is eager to get into the classroom and hopes to leave a lasting mark on students with similar backgrounds as her.

“I’m usually the one that everybody runs to with this kind of stuff. I love being able to be that help,” said De Almeida about working with parents of different backgrounds. “And I think that once I’m a teacher and come back to work in Newark, doing this work officially, I’ll be 10 times better.”

Catherine Carrera is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Newark, covering the city’s K-12 schools with a focus on English language learners. Contact Catherine at ccarrera@chalkbeat.org.

Jessie Gómez is a reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, covering public education in the city. Contact Jessie at jgomez@chalkbeat.org.