The Frank McCourt High School set to open next year had a unique beginning: Instead of being dreamed up by the DOE, a nonprofit group, or a few teachers writing an application, parents played a major role in building it.

But while civic leaders praise the parental involvement, the story of the school’s opening is also a lesson in the challenges a larger community role can bring.

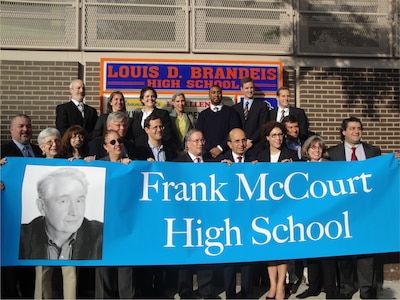

Parent advocates, community leaders and neighborhood elected officials conceived the idea of school last year as a way to honor the famed author McCourt with a school dedicated to literature, writing and journalism. They wanted a school of about 800 to 1,000 students that would attract a diverse population from around their district, which stretches from the Upper West Side to the middle of West Harlem. They also wished to make sure that the school would fit in well as one of several small schools replacing Brandeis High School, which is being phased out.

The school that Chancellor Klein debuted this month hews to that image in important ways. But the DOE’s plan diverges from the parent and advocates’ vision in other ways, most crucially in its size and admissions policy.

Parent advocates and the school’s new principal emphasize that the school is still in its early stages of planning. How those discrepancies are resolved may also be a key part of how the McCourt school provides a model for community involvement in new school development.

Neighborhood parents, civic leaders and elected officials were heavily involved in the process from the start, said Tom Allon, an Upper West Side parent and publisher of the West Side Spirit newspaper.

Allon was approached by City Council member Gale Brewer last spring after Brewer learned that the DOE planned to open a small, selective school on the campus of Brandeis High School. Brewer asked Allon, who had long been vocal about the need for a new Upper West Side High School to lead a planning committee to brainstorm ideas for the school. More recently, Allon led a charge to name a school after McCourt, with whom Allon had taught at Stuyvesant High School and who often joked that schools should be named after teachers, not politicians or celebrities.

As word about the new school and its planning committee spread throughout the Upper West Side and beyond, the number of interested parents and advocates grew. Allon estimates that at their height, committee meetings held over the summer attracted 30 to 40 people.

Allon served as the committee’s primary liaison to the education department and even worked on the DOE’s selection committee, interviewing candidates for the new school’s principal.

The newly-appointed principal, Danielle Salzberg, heard that she’d been selected about a week before the school was formally announced. Salzberg spent 11 years working for the DOE, first as an English teacher at Baruch College Campus High School and then as assistant principal at Millenium High School, a small school in TriBeCa. Salzberg currently works for the nonprofit New Visions for Public Schools, where she provides professional development for the small schools the organization supports. She has also worked in new school development there, and served as the interim principal of the controversial Khalil Gibran International Academy after its original principal, Debbie Almontaser, stepped down in 2007.

Salzberg said that her plan for the school is to teach “21st century literacy skills,” a kind of knowledge that she said embraces and expands upon the school’s language arts theme.

“A big part of the community input called for the school to teach communication skills,” she said. “The idea is to broaden that a little bit. There are a lot of ways to communicate.”

Salzberg’s plan for the school also involves getting students involved in the neighborhood, both through getting them out of school for experiential learning projects and by bringing artists and professionals into the school to work with the students.

Marc Landis, a parent on the planning committee and a Democratic party district organizer in the neighborhood, said that he was encouraged when he met with Salzberg and was impressed by her experience in working with the communities around her previous schools.

“If she brings that kind of approach to the community, it’s the type of community that will love her right back,” he said.

“I think the level of community involvement is what’s unprecedented here — or if not unprecedented, then unusual,” said Clara Hemphill, senior editor at the New School’s Center for NYC Affairs, who was also an active member of Allon’s planning committee.

But while the input from parents and advocates strongly shaped the vision of a school with a creative curriculum emphasizing literacy and the arts, sticking points remain.

Chief among them are how big the new school will be and how the school will select its students. In both cases, parents and community advocates expressed strong preferences that did not appear in the plan for the school that Klein announced.

In August, Hemphill blogged for the Huffington Post that she envisioned a school of somewhere between 800 and 1,000 students:

“That’s small enough to give students a sense of community but large enough to offer art, drama, several foreign languages, Advanced Placement, special education and services for English Language Learners that are often missing at the new small schools that have been created in recent years,” she wrote.

But the school is currently slated to grow to just 432 students, which DOE officials said was the typical size of a small new school. A DOE spokesman, Will Havemann, said that the small size allows for another small school to possibly be opened on the Brandeis campus. A freshman class of 108 students will enter the McCourt school for the first time next fall.

The DOE envisions that the school will stay small, but the parents and advocates involved in the development process are still planning for its growth.

Brewer pointed out that the Upper West Side’s other selective high school, the Beacon School, had also opened with just over 100 students, and had grown to more than 1,000 — the size that many hope that the McCourt school will eventually grow to become.

“We’ll start small, but we’re going to build,” she said.

Hemphill said that there were so many short-term questions about what the school would look like that it was premature to worry too much about the school’s size, a thought Allon echoed.

“Let’s just make a really great school, and if it becomes so popular that in a few years they need to expand, that will be great,” Allon said.

Another sticking point has been the process by which new students are admitted to the school, which the DOE has said will have a selective admissions process similar to many of the city’s other small selective schools.

Parents had called for the school to give preference to District 3 students. Even more sensitive is the call for an admissions policy that would ensure that a small, selective school would not become populated mostly by wealthier, white students.

Donna Nevel, another West Side parent and member of the Center for Immigrant Families, said that concern about the school’s admissions was still on the table. In July, Nevel wrote a letter to the editor of the West Side Spirit in which she called for an equitable admissions process “based on a commitment to having an excellent school of students from diverse backgrounds and with a real range of writing and other ‘skills’ and experience.”

Nevel said that members of her organization, along with a group of other parents, academics and activists, have put together a list of recommendations for the school’s admissions policy that they plan to present at the next public hearing on the school. The school’s final approval requires a vote of the citywide school board following a public hearing and comment period.

Hemphill credits Brewer for doing much of the legwork to make sure that the school draws from a diverse population from all around the district.

“She’s been really good at bringing people together people of different neighborhoods, races, philosophies,” she said. “The school has a constituency.”

The school is still in relatively early planning stages, and advocates expressed hope that with Salzberg’s expressed commitment to involving the school’s neighbors in its planning and the precedent they’ve already set of being heavily involved, they will continue to shape the form the school takes when it opens its doors next fall.

“I think its all still a work in progress,” Hemphill said. “I don’t think anything has been set in stone except the name and the building. Everything else is up in the air.”

Allon said that, assuming the school does in fact become what is currently being planned, the whole process could be a powerful example of how neighborhoods can design schools to suit their own needs, in cooperation with the DOE.

“I think it’s so exciting that the DOE is open to taking these kinds of risks and coming up with these kinds of theme schools,” he said. “Allowing local communities to not just have input but to really drive the process — it’s been great.”

He added that the most important thing going forward is to focus on how the school should best preserve the McCourt’s legacy. He pointed out that McCourt helped his students find their own voice, but it was through teaching that McCourt found his own literary voice as well. That process, he said, should serve as a guiding principle for the school.

“If this high school can be a place where kids can literally and metaphorically find their voices, then it will be a fantastic school,” he said.

Read more at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/clara-hemphill/honoring-frank-mccourt-wi_b_250222.html