Principals could swap schools for a year under an unusual — and under-the-radar — provision of the city’s contract agreement with the school-administrators union, city and union officials said Monday.

The new “ambassador” program would let principals and assistant principals draw hefty bonuses by trading places with leader teams from other schools for a year to exchange ideas. Another provision creates a new class of higher-paid “master” principals who could go prop up one struggling school for a year and then move onto another, union officials said.

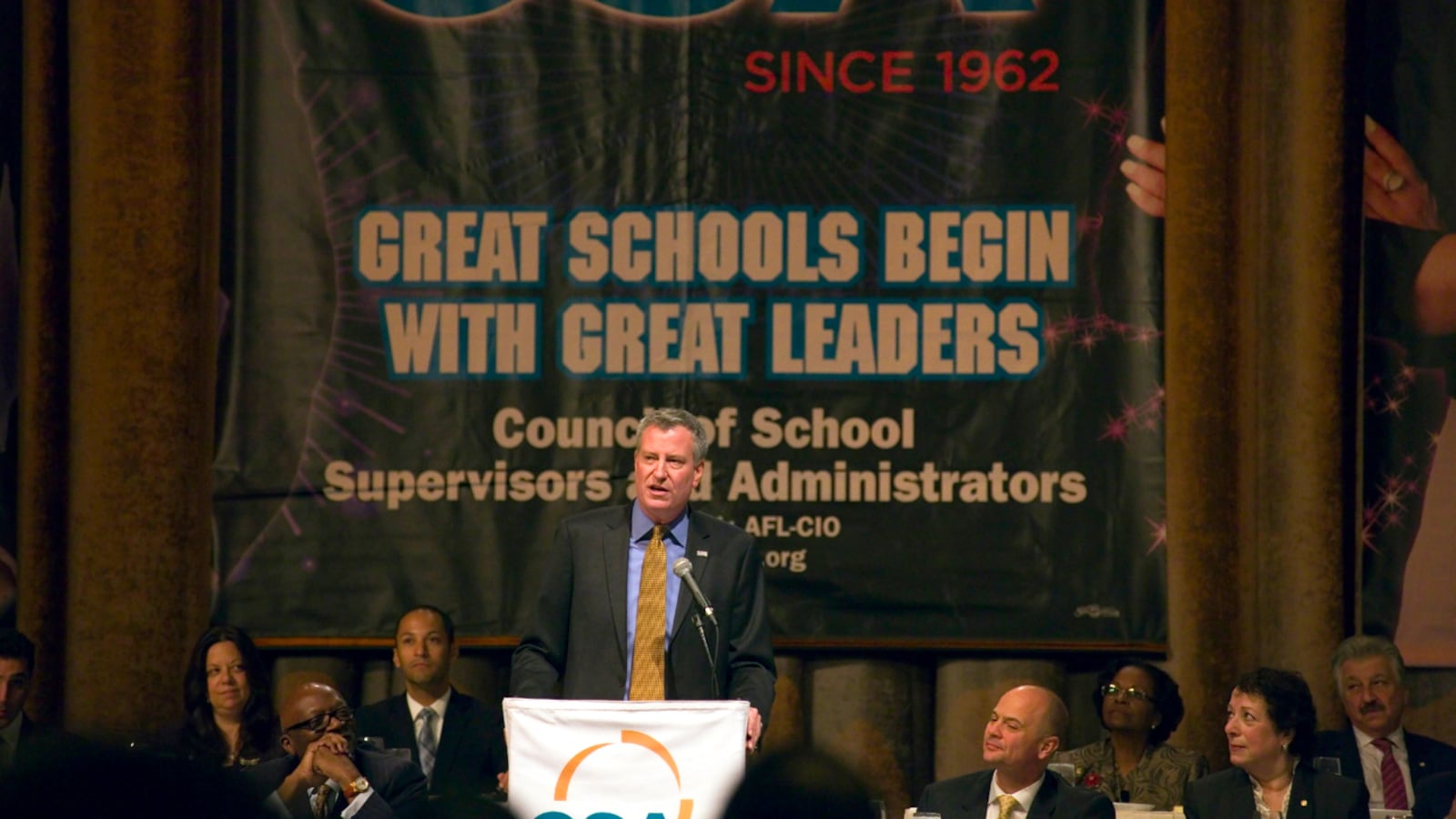

The new details emerged days after Mayor Bill de Blasio and principals union president Ernest Logan announced the contract deal but did not highlight the principal swaps or the rotating master principals. Instead, they said Saturday that the ambassador teams would take over troubled schools and the master principals would simply take on new duties like “coaching their colleagues.”

Both initiatives reflect Chancellor Carmen Fariña’s conviction that schools benefit when educators share their expertise, and officials explained on Monday that the new positions could be used in various ways. But the new details raise questions about how the roles will work as intervention tools at troubled schools, experts and former principals said Monday.

For instance, if the city uses the exchange program as a turnaround strategy, will struggling school leaders be charged with leading successful schools? And will one year be enough for ambassador or master principals to set floundering schools on a new path?

“I’m dubious about quick turnaround plans,” said said Brooklyn College Education Professor David Bloomfield. “It seems to me that if it discourages stability, it’s a bad idea.”

The principal-exchange program will be voluntary, said Mark Cannizzaro, executive vice president of the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators. Leaders from struggling and stable schools will both have the option to join the ambassador program, he added, which offers $15,000 bonuses to principals and $10,000 to assistant principals.

“The idea is that each group would get to see the innovative things that are happening in the other school and could take it back to their original school,” he said.

City Hall described the ambassador program differently in a press release Saturday.

It said that “expert teams” of principals and assistant principals “will be brought in to fill vacancies or take over leadership at struggling schools,” and that after one year the teams can choose whether to stay at the turnaround schools or return to their own schools. An education department spokesperson said Monday that the one-year option may entice some seasoned school leaders to take on a tough turnaround assignment.

Meanwhile, the master-principal position was described as letting high-achieving leaders earn $25,000 more per year by taking on extra responsibilities. “This will leverage great leaders across the city,” the release said.

Cannizzaro, of the principal’s union, described some of the possible extra duties on Monday.

A master principal could potentially go into a low-performing school for a year or so and try to help turn it around, then train successors there to take over before moving onto another troubled school, Cannizzaro said. The principal could work with three or four schools that way, while still maintaining some oversight of their original school, he said.

“The principal will go over to a school that has been deemed struggling and offer all of his or her expertise, get that school up and going, and eventually the hope would be that another leader from that school would emerge and be able to take over,” Cannizzaro said. “Then the master principal could move onto the next challenge.”

Geraldine Maione, a former principal who helped turn around William Grady Career & Technical High School in Brooklyn, commended the administration for coming up with another way to intervene at the city’s lowest performing schools. But she questioned the idea that any principal can revamp a school in one year, noting that it had taken her longer than that just to assess the situation at Grady and earn staffers’ trust.

“You don’t just go in and turn everything upside down,” she said.

Geoffrey Decker contributed reporting.