Thomas De Castro, a certified preschool teacher with two bachelor’s degrees and a master’s degree in the works, teaches at a childcare center inside an East Harlem housing project.

If he taught pre-kindergarten at the public elementary school a few blocks north, he would earn about $9,000 more per year than he does today. Once he earns his master’s degree, he’ll lose out on about $12,000 annually because he isn’t in a public school.

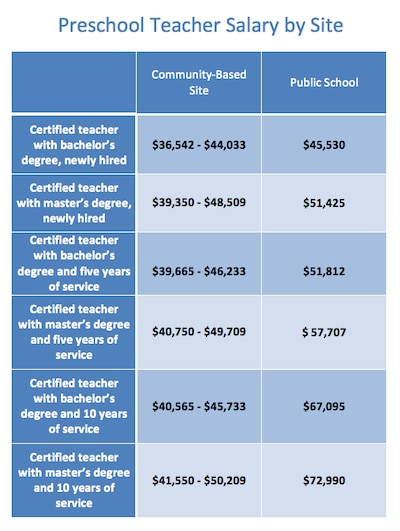

The same is true for the other teachers in the roughly 850 independently run public pre-K sites across the city: depending on their union membership and credentials, they can make upwards of 40 percent less than comparable pre-K teachers at public schools, who pull in full teacher salaries and benefits.

Researchers and pre-K providers say that pay gap drives some of the most experienced teachers to public schools, fueling a “tale of two cities” within the public preschool system. De Blasio’s sweeping plan to provide free pre-K to all four-year-olds calls for “comparable” pay and more oversight for all preschool teachers, which those close to the system say is essential if the mayor wants to raise the quality of pre-K across the city.

David Nocenti, executive director of Union Settlement Association, a nonprofit that operates seven free childcare centers in East Harlem, including the one where De Castro works, said such fixes are long overdue.

“If you’re a child,” Nocenti said, “the quality and salary of your teacher shouldn’t depend on whether your closest pre-K classroom is in a center like mine or a public school down the street.”

A “mixed bag” of preschool sites

About 40 percent of the city’s free preschool seats today are in public schools and about 60 percent are in childcare centers operated by groups that contract with the city.

Public school pre-K teachers, who are part of the city teachers union, need a college degree and a state teaching certificate. The head pre-K teachers at childcare centers also must have a college degree, but they can start teaching without a certificate if they have a plan to earn one within five years.

Pre-K teachers at childcare centers, even credentialed ones with advanced degrees and years of experience, earn far less than their public school counterparts. Meanwhile, teachers at most centers face longer hours and more school days but receive less generous benefits than public school pre-K teachers.

The compensation gap partly reflects the bargaining might of the city teachers union. But it mainly stems from funding — the childcare centers, which must pay for rent and staff training, have tighter budgets than the public school system.

“We don’t have that kind of money in the budget when we sit down to negotiate,” said Raglan George, executive director of DC 1707, the union representing most workers at the childcare sites. The union’s contract with the city expired in 2006.

Such disparities make it difficult for childcare centers to recruit and retain highly qualified preschool teachers.

Michelle Paige, Union Settlement’s director of early childhood education, said she dreads bringing up pay with teacher applicants.

“You tell them what the salary is and they leave,” Paige said. Or, she added, “they’ll take it with the caveat” that if a public school position opens later, they will apply for it.

Sometimes new teachers hone their skills for a year or two at childcare centers — with the help of staff training and mentors — then move to the Department of Education, said Linda Flores, director of early childhood services at Henry Street Settlement.

“We’ve had teachers who come in with no classroom experience,” Flores said. “They gain that here, then they step up to working with the DOE.”

That brain drain can weaken the programs at childcare centers, which are left with fewer experienced teachers with advanced degrees, higher turnover rates, and lower staff morale, according to a policy paper by W. Steven Barnett, director of the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University. Uncertified teachers at these sites may also have less money and fewer incentives to invest in education and, due to lax oversight, go years without fulfilling their study plans.

Some groups, such as Union Settlement, invest in training and quality controls to counteract the recruitment and retention challenges. And many skilled teachers prefer to work at childcare sites or stay there because public school pre-K positions can be hard to find. (Currently, about six people apply for every open public school position in the city, with 2,000 early childhood-certified teachers vying for slots each year.)

Barnett said limited data exists on preschool quality, but that the city’s community-based preschool sites are likely a “mixed bag.”

“Some places probably manage to do a pretty good job despite not having a lot of money,” he said. “Other places don’t.”

Plan aims for quality pre-K at every site

De Blasio’s pre-K expansion plan, which seeks to add more than 40,000 new full-day preschool seats in public schools and childcare centers, includes “a commitment to develop comparable salaries for teachers who have the same credentials,” said Sherry Cleary, a member of the six-person team tasked by the mayor with creating an implementation guide for the expansion.

Cleary said the pay hike for childcare center teachers was factored into the plan’s estimated budget of $10,239 per child, which is more than $3,000 above the current cost per pre-K student. The city will need to negotiate a new contract with DC 1707 to adjust the teachers’ pay, but Cleary said that should not be a problem.

“I’ve never met a union person that didn’t want their people to earn more,” she said.

Several researchers said pay increases would only improve preschool quality if they are coupled with accountability and support measures — otherwise teachers would be paid more for the same work, whether or not it’s effective. The mayor’s plan includes several such quality controls.

The Department of Education would help recruit undergraduate students interested in teaching preschool and assist childcare sites in selecting qualified teachers, according to the implementation blueprint and agency officials. The department would also enhance a system that tracks teachers’ progress toward earning their state certificates and create a “quality assurance team” to evaluate sites and teachers. And it would provide on-site coaching to all pre-K teachers along with a weeklong summer training.

With better pay and benefits, childcare centers could hire teachers whose education, experience, or other skills make them more competitive.

Today, many certified pre-K teachers move to other grades or leave the profession rather than work in low-paid childcare centers, several people said. Meanwhile, many college students who are interested in teaching preschool pursue other tracks because of the limited number of well-paid pre-K slots at public schools, said Harriet Fayne, dean of the School of Education at Lehman College.

She said hundreds of students minor in early education each year, but “relatively few” complete the certification process due to the tight job market. If the pay and prestige of childcare care centers approached that of public schools, many of those students would be enticed to earn their certificates and enter the field, Fayne added.

“Now that there’s gold at the end of the rainbow,” she said, “I’m going to guarantee you that you can ramp up very quickly.”

Correction: The chart included with this article originally listed incorrect salary figures for public school teachers with five years of experience.