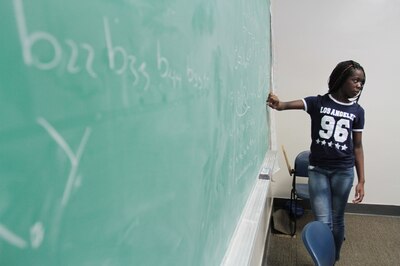

Jennora Blair wasn’t about to miss her first real college lecture.

The 13-year-old middle school student from Brooklyn knew that “Darwin, Mendel and the Origins of Life” was about to start in Yale University’s William L. Harkness Hall. But as she walked quickly across campus, class schedule in hand, she didn’t know whether she was headed in the right direction.

“It’s like our first day of college. We don’t know where we’re going,” she joked.

Blair and her friend made it to watch the lecture on that recent Saturday morning, thanks both to a campus map and a growing nonprofit program that gives an extra boost to seventh-graders from low-income city schools with a certain “spark” for math.

Called Bridge to Enter Advanced Mathematics, or BEAM, the nonprofit launched in 2011 with a goal of shepherding promising students into careers in science, mathematics, engineering and computer science. Unlike other New York City-based programs that target black and Hispanic middle school students with a laser focus on getting them into a specialized high school like Bronx Science, BEAM is set on expanding students’ passion for math — and guiding them past high school into college and a career.

That starts with a three-week overnight camp the summer before eighth grade that immerses them in advanced mathematics. For the next five years, the staff focuses on getting the students into high-performing high schools, prestigious academic programs, and then college, offering application guidance and a new pool of connections.

“We try to be that informed and involved parent, where a lot of times — if they’re in a single-parent household and that parent works a number of jobs or doesn’t speak English — they don’t have those resources,” said Dan Zaharopol, the program’s founder and executive director.

Nearly 90 percent of the students in the program — which has grown to 250 current eighth-graders through high school seniors — identify as black, Hispanic or Native American, and 80 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. The median family income of the group is $25,000.

Zaharopol, who studied mathematics at MIT and the University of Illinois, said the program is meant to expose students to abstract reasoning and more challenging problem-solving than they get at their middle schools. But the trips to Yale and summer programs at local universities are also meant to address the non-academic challenges students are likely to face as they work their way into industries driven by science and math.

“I come very much from the hardcore math world where there’s an incredible lack of diversity,” he said. “We want them to be comfortable when they go to other programs where they’ll be doing advanced study, but where the majority of the kids are, frankly, going to be white and Asian and affluent.”

Dawntae Evans, whose 15-year-old son has been working with BEAM since middle school, said the program helped her son get into another math camp at Texas State University for six weeks. Since the start of the school year, he has also been going to Goldman Sachs once a month for a mentorship program.

“Sometimes it’s not so cool to be smart and it’s not so cool to like math,” she said. “But now he’s one of the cool kids.”

To find its students, BEAM partners with 35 district and charter middle schools where at least three-quarters of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. The program doesn’t look at grades, state test scores, or past academic performance, focusing only on a math problem set and an interview.

That approach has worked well, Zaharopol said, and ensured that students who might have struggled early in middle school aren’t shut out.

By the summer after seventh grade, students are spending seven hours a day doing advanced math at Bard College and Siena College. This past summer, for example, 80 incoming eighth-graders worked in groups on single math problems that took up to three hours.

“You don’t know that it’s college math until the very end,” Blair said after working with her fellow 12- and 13-year-old campers to solve a problem. Her teacher later told them it was based on a concept that he didn’t understand until his second year in college.

“You feel like you’re doing math, but it’s not normal math,” she said. “It’s math that you really have to think about.”