When Samantha Pugh walked into City Hall last week, the principal was as giddy as the two 14-year-olds she arrived with.

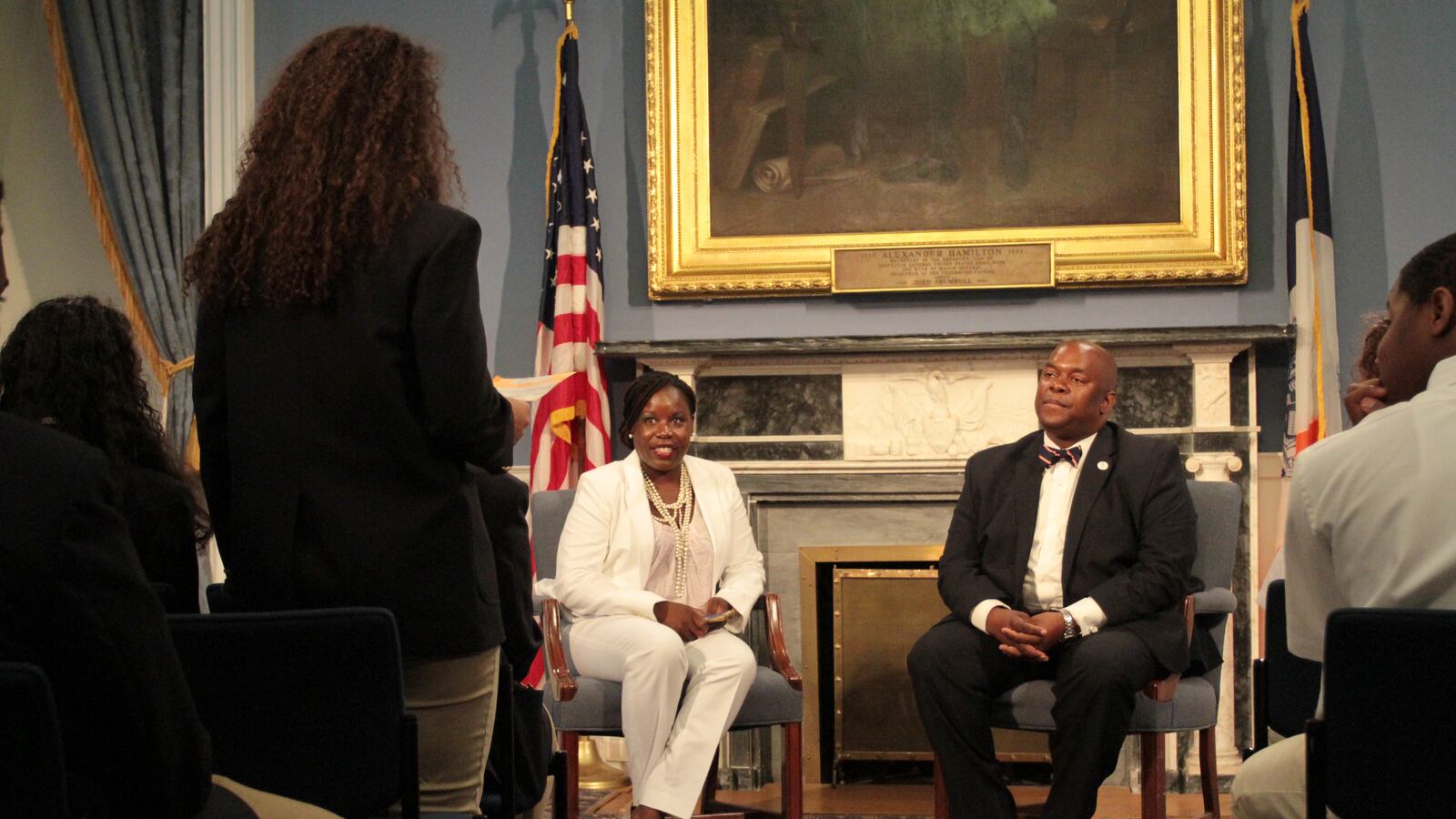

It was the first time at City Hall for all three, and they took a few selfies, admired portraits of former mayors, and stood behind an official podium as they waited for more students to arrive. The 50 or so incoming ninth graders were there to question Deputy Mayor Richard Buery, who has spearheaded the city’s pre-kindergarten expansion and whose work some said they hoped to emulate.

Come September, the students will be a part of the 127-member inaugural class of the Charter High School for Law and Social Justice in the South Bronx. They were already together thanks to a four-week summer program designed to give the students an introduction to law and to high school — guidance Pugh said she had missed during her own school switch.

“I didn’t really have a smooth transition between middle school and high school,” said Pugh, who attended Brooklyn Technical High School, “and to be honest, I wasn’t academically prepared for the rigor and what I needed to do to be successful.”

The summer program was designed to give students some of those academic skills and exposure to real role models.

“We tell our kids that you can be a lawyer, but they need to actually feel the experience, sit in a law school classroom, sit in a college classroom, see actual lawyers and see lawyers of color,” Pugh said.

Chalkbeat listened in as the students talked to Buery. Here are some of the students’ questions, and what the deputy mayor had to say in response.

What did you struggle with in high school?

“For me, going from middle school to high school was a really hard transition,” Buery said. “It was hard because I grew up in Brooklyn and I grew up in a black and Latino neighborhood, so I was just socially intimidated going to Stuyvesant. I was worried I wouldn’t be able to do the work, I was worried I wouldn’t make friends, I was worried I wouldn’t fit in, so I struggled socially a lot.”

“By the time I graduated, I loved high school,” he added. “I made great friends there, but it took a while. It didn’t happen overnight.”

How does the law come into play in being a social justice leader?

“While you don’t have to be a lawyer to impact social change, it’s almost impossible to enact social change without having the ability to impact and manipulate the law,” said Buery, who attended Yale Law School.

“The law is really intertwined with all the things that make life in America so challenging right now. Whether you live in a good neighborhood or a bad neighborhood, if you have access to good housing or good schools — ultimately, all of those things are defined by laws. It may not be the laws coming right from the book, but it’s the way that government officials make decisions.”

Is it difficult being a person of color in your position?

“The more that I’ve had opportunities to lead, I don’t let it bother me,” Buery said. “In my mind, I don’t see any limitations that come from my race or my ethnicity, but we do live in a world where race and ethnicity matters.”

“The key for us is to not let our race or our ethnicity stop us from doing what we believe, but also to understand that we live in an environment … where the world is not organized fairly and the world is not always organized for our success,” he said.

Who inspires you?

“I have a lot of friends and peers who I think are doing extraordinary things in the world,” he said. “I have a lot of friends and peers who started schools, they started very successful charter school networks. Dave Levin who started KIPP Foundation who’s a friend, Dacia Toll who started Achievement First is a friend that I went to law school with … I’m inspired and challenged by them.”

What advice do you have for us?

“Be bold. Be brave. Take chances. Do what feels challenging. Do what feels scary,” he said. “Know you’re going to mess stuff up.”