When Leo Herrera is at School for Excellence, a small high school in the Bronx, it can be hard to concentrate.

Sometimes, Herrera says, it’s girls. Sometimes, it’s feeling surrounded by classmates “that don’t really care and can hold you back.”

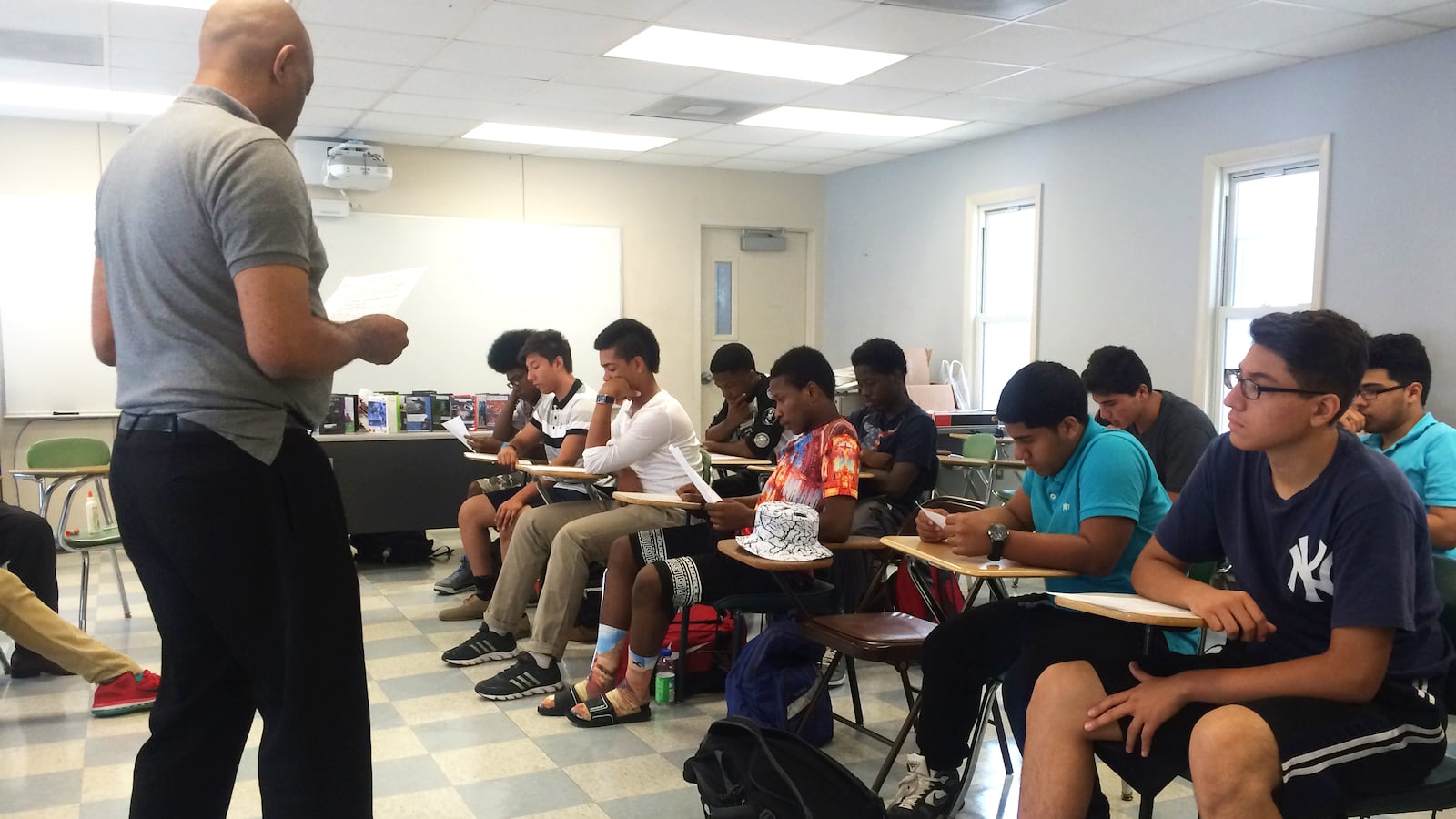

But when he’s at SAT prep or debating with peers in a classroom at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn, he’s more focused than ever. Herrera is part of a city program designed to send black and Latino male students to college. And not just any college: selective, four-year schools, perhaps out of New York City altogether.

“This program is completely different than my school,” Herrera said during an SAT prep session one Wednesday this summer. “In my school, I personally have distractions that take me off sometimes. But luckily I’ve got these guys that always keep me on track and remind me where I want to go.”

The program is called Urban Ambassadors, and is focused on a small group of promising students handpicked from high schools that don’t typically send many (or any) students to selective colleges. The students then get academic tutoring, help with college applications, and one-on-one mentoring, and are surrounded each week by a very motivated group of peers.

The result is something like the Posse Foundation scholarships, which send low-income students to colleges in groups, but for college preparation. So far it’s had impressive results: Of the program’s two groups of graduating seniors so far, 22 of 27 in the first cohort enrolled in college, according to Ainsley Rudolfo, the program’s director. This past year, 26 of 28 students enrolled at colleges, including Syracuse University, Middlebury College, Brandeis College, and Drexel University.

"It’s been infectious, with kids coming back and recommending it to their peers."

Perry Rainey, Brooklyn School for Math and Research principal

“We know that black and Latino boys tend to look at their peers in particular for college,” Rudolfo said. “So our thought with the program was, could we develop these young men that are all about college? And would their peers then follow them and say, ‘I want to be like them’?”

To get into the program, which is overseen by the Department of Education’s equity and access division, students must qualify for free or reduced lunch and have at least a 2.5 grade point average, then go through an application process and interview. Rudolfo says they aren’t necessarily looking for a school’s top academic performers, but they are looking for dedication and charisma.

Its students commit to an intensive schedule over their junior and senior years of high school. Herrera has spent his summer weekdays at Medgar Evers, and will continue to spend his Saturdays with the group for two years. The students visit colleges, get special leadership training, and prepare to take the SAT together in December of their senior year.

On a recent Wednesday, students were preparing for a debate about whether the Common Core standards helps black and Latino students. More than 20 rising juniors from across the city were discussing who they would impersonate — President Barack Obama, Rev. Al Sharpton, or Chancellor Carmen Fariña. (Kellon Garrick, a rising junior at Urban Assembly for Law and Justice in Brooklyn, asked if picking a less well-known character, like Diane Ravitch or the police commissioner William Bratton, could qualify him for extra credit.)

The goal, Rudolfo explained, is to give students a better sense of what has shaped their own education.

“We’re learning about how the system affects us so we can make informed decisions,” Garrick said.

The program was founded in 2012, in partnership with Hip Hop 4 Life, a youth empowerment organization, just months after the city launched the Young Men’s Initiative, designed to increase college- and career-readiness of black and Latino young men in the city.

Urban Ambassadors is too small to tackle more than a corner of that problem, and its first students are just now entering their sophomore year of college, making it too early to tell whether the program will succeed in helping its students surpass the roadblocks that keep many similar students from graduating. In 2010, the college graduation rate for Latino male students was 10 percent lower than the national average for male students; for black males, it was 22 percent lower.

But as the city has started high schools and funded anti-violence programs through the Young Men’s Initiative, Urban Ambassadors fills a different gap, helping students with academic potential who are already in high schools that can’t offer the same kind of sustained, one-on-one guidance.

Before their debate that Wednesday, the students wrapped up a project focused on how they could create a “personal brand” to help during their college searches, creating DVD cases with concise descriptions of themselves.

Those activities and others are aimed at making students feel confident in their ability to pitch themselves to college interviewers, and comfortable with their peers, who they call brothers. During school breaks, students visit colleges to get a better idea of what colleges look like, visiting schools like Morehouse College, Georgetown University, and SUNY Albany.

“Without the program, I just don’t know — I didn’t know what a college campus looked like,” said Justin Summers, a rising senior at Brooklyn School for Math and Research. “And now my vision is really going out of state and being successful.”

"Without the program, I just don’t know — I didn’t know what a college campus looked like."

Justin Summers, student at Brooklyn School for Math and Research

Edward Fergus, an education professor at New York University, said it’s important that programs aimed at getting low-income students into college offer chances for students to have conversations with college students with similar backgrounds.

It’s critical that students are “gaining a better sense of not only what it means to go to college,” he said, “but also how much they envision themselves being ready for college.”

Students acknowledge that Urban Ambassadors, which has an annual budget of $175,000 for each cohort, offers resources their high schools can’t, since many of their schools do not send many students to four-year schools and have guidance offices that are already stretched thin. At School for Excellence, 12 percent of graduates went on to a four-year university in 2014. At Pan American High School in Queens, which is designed for students who are new to the country, one-quarter of seniors that year went on to a two-year CUNY program, but almost none went into four-year programs.

“Where I come from, you just don’t get opportunities like this every day,” Herrera said. “My school is not that good of a school, so we don’t have SAT prep classes and that’s something I’ve always wanted.”

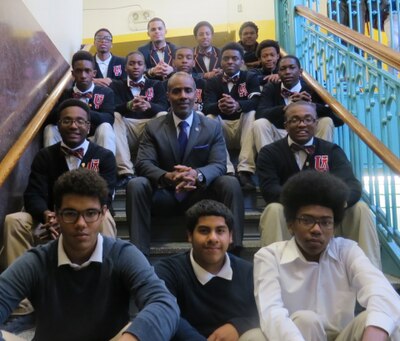

Perry Rainey, principal of the Brooklyn School for Math and Research, says the program offers some resources that a small school like his cannot pay for. He is such a strong proponent of Urban Ambassadors, which currently includes 12 of his students, that the school hosts an open house for parents of 10th graders to explain why they should encourage their kids to apply.

“The program really helps those kids that need an extra push,” said Rainey. “It’s been infectious, with kids coming back and recommending it to their peers.”

Efrin Martinez, a rising senior at Pan American International High School, came to New York from Dominican Republic just two years ago. For him, the group is more than just a chance to visit colleges. The group has helped him improve his English, adjust to his new surroundings, and convince him that attending college is a realistic prospect.

“It’s not that there aren’t students in my school that want to go to college and do good,” Martinez said. “But for us, it’s about making sure we all succeed, because I want my brothers to go far too.”