Shaka’la Maxwell, a Bronx high school student who helped survey her peers about school discipline, recently asked a classmate why she had been suspended.

The girl explained that she had fought with another student who questioned her intelligence. But she also made clear that her problems went deeper than a schoolyard taunt.

“Basically,” Shaka’la explained, “she struggled in class a lot.”

That student was not alone: In surveying nearly 400 students, parents, and teachers at over 50 Bronx schools, Shaka’la and her research team found that students who struggle academically or socially at school are also more likely to get into trouble. Those same students are also the least likely to turn to school staffers for help, according to a new report by the New Settlement Parent Action Committee, the South Bronx advocacy group that conducted the surveys.

The report comes as the citywide suspension rate continues its steady descent, and the education department is encouraging schools to adopt less punitive discipline approaches. It also follows significant changes to the city’s school discipline policies last year — including restrictions on the use of suspensions — and City Hall’s formation of a task force to review school discipline practices.

But, the report suggests, those efforts will fall short if they fail to address the underlying reasons for student misbehavior, which often involve a mix of academic challenges, problems at home, and friction with peers.

“While there is important and critical work being done to change policing practices and discipline policy,” the report says, “our research suggests that policymakers and educators must also address these underlying factors in order to transform school climate and culture in New York City.”

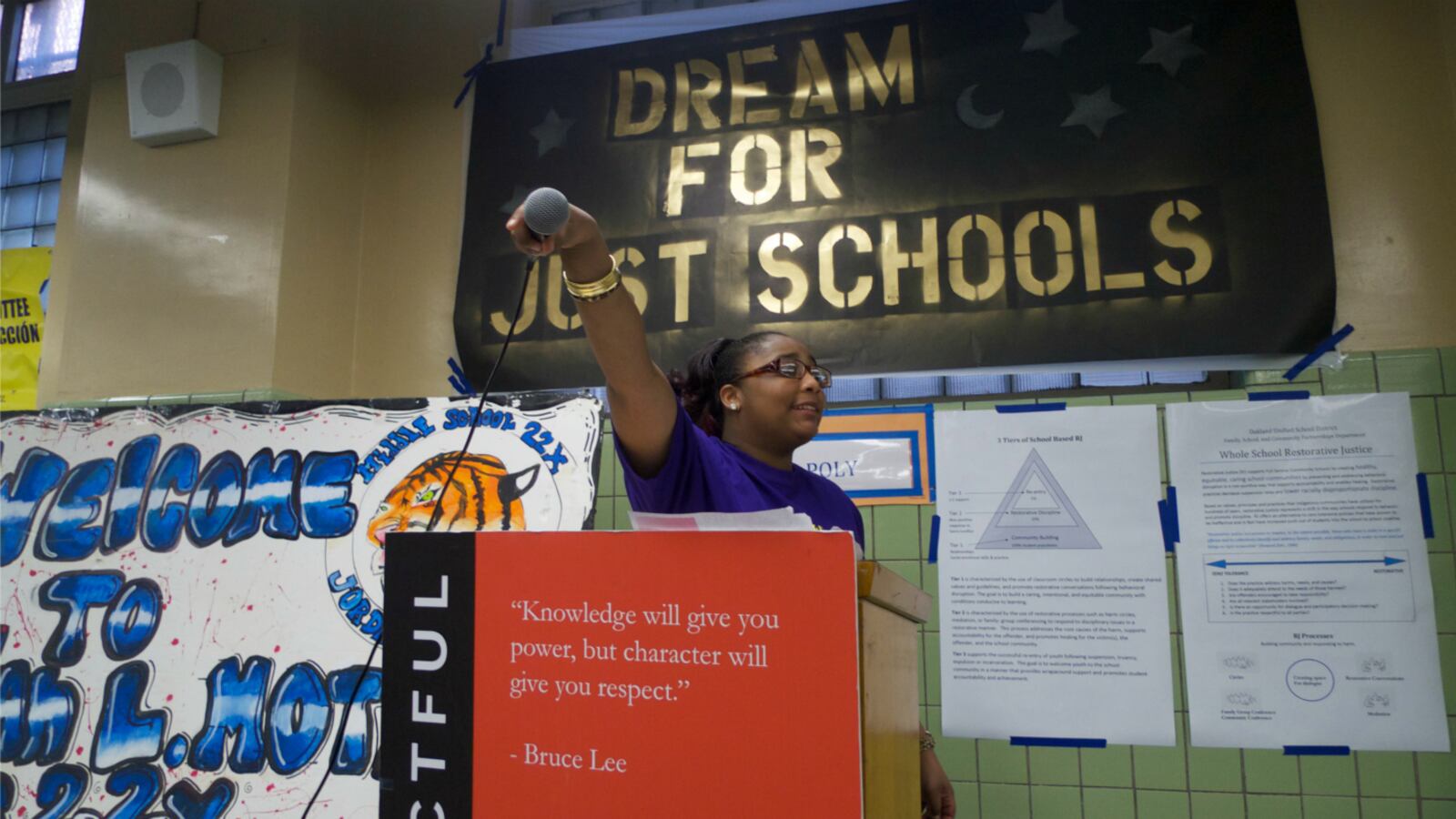

The group, which has pushed for improvements to South Bronx schools for two decades, decided to survey Bronxites about their schools in order to expand the school-safety debate beyond suspensions and metal detectors. While their unscientific results could never match those of the city’s massive school survey — which involves nearly 1 million participants — the idea was to add more school-level voices to the debate.

Shaka’la, who is a junior at the Bronx High School of Medical Science, teamed up with fellow students and parents to conduct the surveys in school lunchrooms, parks, McDonald’s restaurants, and churches. (Shaka’la said she used candy bars to coax some reticent interviewees.) Overall, they found that more than half of students said they enjoyed school both academically and socially.

But one in five students said they did not enjoy school, and those were the ones most likely to report having been disciplined in school and having struggled on state tests. Those same students were also twice as likely to say that they would not seek help from a teacher or other school staffer, according to the report.

Many of those students end up abandoning school, according to the report, which is based partly on interviews with students who dropped out of high school. The report says those dropouts were actually “pushed out,” explaining that many were “disengaged, distracted, disciplined, and dismissed long before they stopped attending.”

That was the case for Schurch Burgos, a 21-year-old Bronx resident who said she dropped out of long-struggling DeWitt Clinton High School when she was 15. She said that no one tried to pull her up as she fell behind in her classes, until she finally decided that it was pointless to keep showing up.

“I didn’t have help from teachers, from nobody,” said Schurch, who is now studying to earn a high school equivalency diploma. “I felt lost.”

If someone had intervened, she added, she believes that “would have stopped me from leaving, and I think I would have graduated.”

These issues are especially acute in the Bronx, which continues to have the lowest graduation rate and highest dropout rate of any borough. The Bronx has also historically seen the most school arrests and suspensions, though those numbers have declined sharply since 2012 along with the rest of the city’s.

The report makes several recommendations. It calls for more social workers to help coordinate schools’ “restorative justice” efforts, a problem-solving approach meant to replace suspensions. It also advocates substituting projects for some standardized exams, which it says will make students more excited about school and help those who perform poorly on tests.

An education department spokeswoman said the report is misleading because it relies on a limited sample of people. She said the city has hired 250 new guidance counselors and offered conflict de-escalation training to some schools, and she noted that suspensions fell by 17 percent last year.

In addition to the discipline-policy changes, the city has also invested heavily in mental-health counseling and other social services at some 130 “community schools” — efforts to confront the root causes of misbehavior and poor academics highlighted by the report.

“It’s an exciting moment,” said Emma Hulse, a Parent Action Committee organizer, “but there is a real need to continue the work and move forward.”