I am a Latina. I am proud of that identity. But that identity wasn’t affirmed by anyone outside my family until I was in college. I teach because I want to change that for kids.

My mom is Mexican, my dad is Puerto Rican, and I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. There, the word “Hispanic” was nonexistent – you’re born on the island, and you’re like everyone else. Then we moved. The moment I set foot in California, I was different. I was the kid who didn’t speak English, the kid whose parents didn’t speak English. I went from being like everyone else to being “the other.”

There, I didn’t see a lot of role models who were like me. Even through college, I could count the number of Latina teachers I had on one hand. Thankfully, things changed my last year of college. I met my mentor, the first professor who could speak to me directly about things like, “This is racism, and this is how it affects you explicitly and implicitly.” She showed me what a big deal it was that I was an ESL student, the daughter of parents who didn’t speak English, the daughter of a dad who didn’t finish high school, and made it as far as I had.

This was the first time someone called me something other than a good student. She called me a “mujer with a story.” She also challenged me to use my story to impact others. It was no longer enough to just do well in life; it was time to help la causa, el pueblo.

Teaching seemed like the only field where I could do this, and Teach For America was my outlet. I taught in Houston for four years before coming to Brooklyn. My current struggle is figuring out, what do I do now with this power and knowledge that I didn’t have five years ago?

My answer, for now, is that in my class we talk about identity, history, and the importance of being bilingual and bicultural. Once I made the choice to get in front of a group of kids, it became my responsibility to recognize that I am a mirror to many of my students: Latina, woman, queer, language learner, first-generation college student, bilingual, and a member of a beautiful and under-appreciated culture.

I’m teaching beginner Spanish and an intermediate class for native Spanish speakers. We’re reading the novel “Casi una mujer” by Esmeralda Santiago. It’s been great because I am able to take kids on a journey of self-exploration in a safe and affirming environment. I have ninth-graders asking me questions like, “Why is the language Spanish so sexist?” “What should I do if my family is also very judgmental?” “Why are Latinos all so different?” or “Why can’t I call someone Spanish if they speak Spanish?”

Had it not been for my mentor, I never would have understood how racism, classism, sexism, and homophobia affect me and my community every single day. I am honored to guide students in this process, and to affirm their identities while also pushing them to love and affirm others.

Ultimately, my class is about stories. I tell students that, if you don’t want to judge a book by the cover, you need to read the story. I tell my students, “Don’t be afraid to ask people. Learn from them.”

I want to help my students realize that our world is a painful place to live in partially because too many people rely on stories perpetuated by stereotypes in the media. If we work a little harder at creating safe dialogues with one another, we can have a more welcoming world.

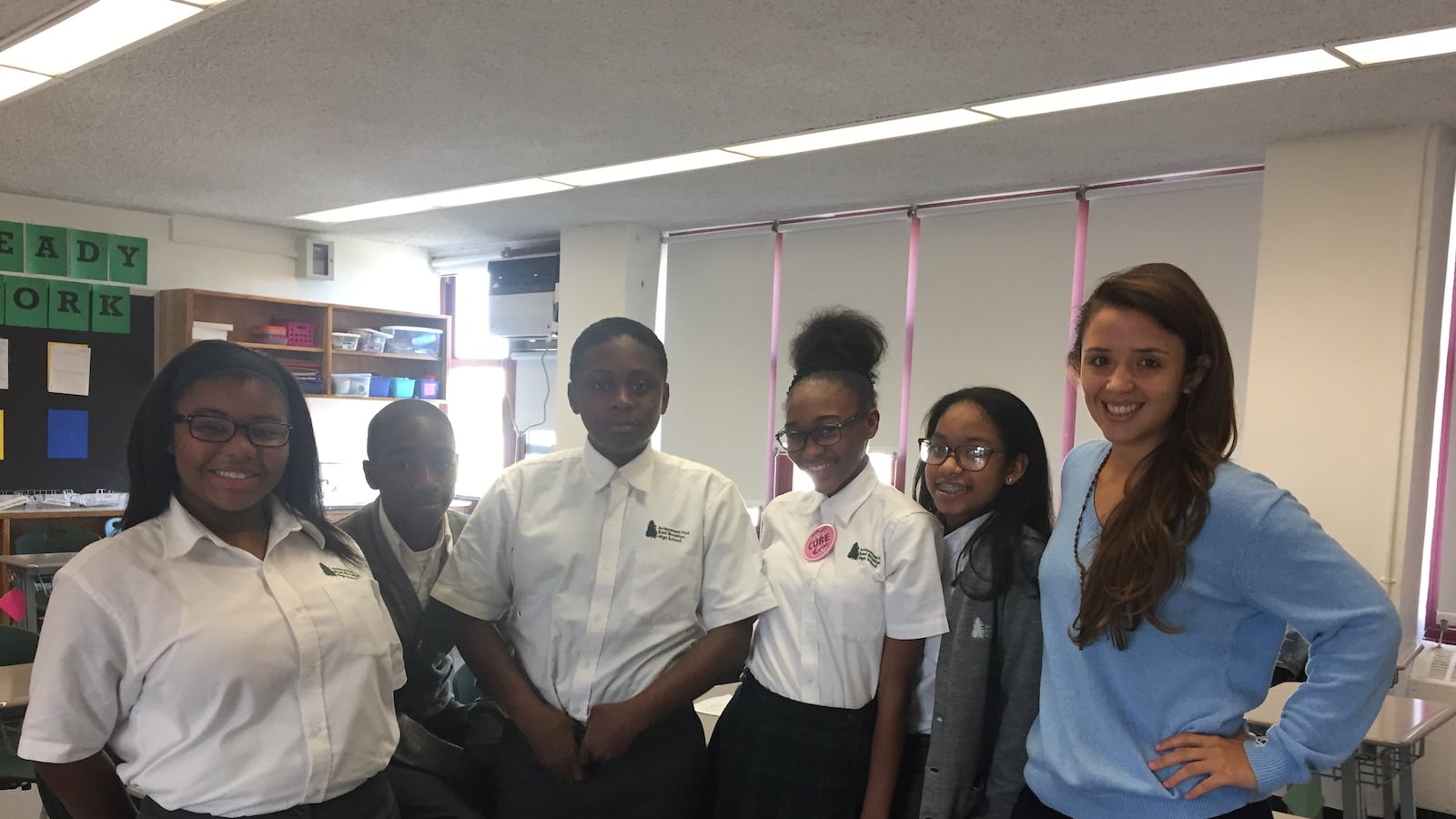

Mariangely Solis Cervera is the founding Spanish teacher at Achievement First East Brooklyn High School. This piece first appeared on the Achievement First blog.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.