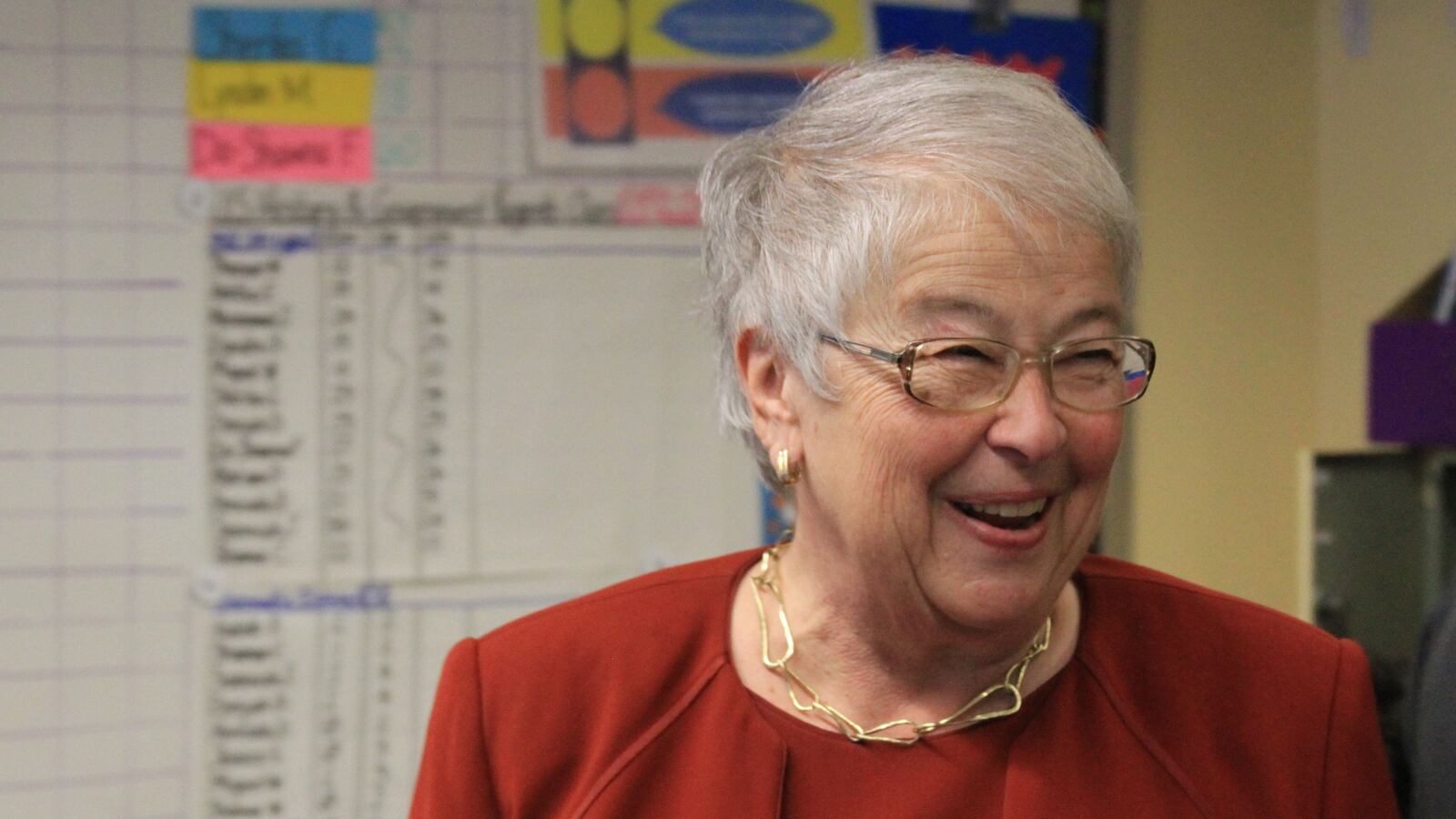

As Chancellor Carmen Fariña marches into her third year on the job, she can point to graduation rates and test scores that are moving in the right direction.

But, during an interview last week with Chalkbeat, she was just as likely to cite different metrics: The number of teachers who attended a workshop, the share of faculty members who are satisfied with their weekly trainings, the number of guidance counselors who emailed her messages of gratitude.

Those measures are crucial to Fariña because they cut to the core of her theory of school management: That schools improve and students learn only when the adults in the building are happy, well-trained, and working together. She gathers heaps of data on those measures herself, through hundreds of school visits, public forums, and emails.

Many educators and parents praise Fariña’s school-by-school approach, saying they feel respected and reassured by her intimate knowledge of the system.

But her critics often scoff at it. Those who identify as education reformers (a label Fariña also applies to herself) say her theory of change is too incremental and founded on experience over research, while some principals complain about micromanaging.

However, Fariña insists her changes are working: Just look at the numbers, or read the grateful emails.

Here are some excerpts from our conversation, condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Chalkbeat: You’re now in your second full school year as chancellor. How would describe your vision for where the schools are headed, and your agenda? When you see all the things happening at individual schools, how do you take back what you see in and create a larger vision?

First of all, certainly student achievement — we have to see it grow in every single place.

Pre-K is key, because I want to see all pre-K students graduate with more stamina for kindergarten. And certainly I look at the writing when I go to schools. Are we increasing vocabulary? Are we increasing parent workshops so these parents will be invested in these kids’ careers forever?

I’m looking at second grade. Are we getting the literacy piece going? One of the things we’re doing this coming summer is a lot more summer school placement for second graders. Also, in seventh grade, a lot more after-school programs that deal with social-emotional issues.

I think getting the message out to parents and the business community that everyone needs to be invested in success. And for all this to happen, we need to have professional development. You can’t ask teachers to do things, particularly things like Common Core, without giving them the tools. So we now have given them unit studies, we’ve given them books, we’ve given them everything possible, including training.

That’s the sort of thing I feel is crucial: professional development, across the city, where all teachers are treated equitably. I came from two districts that were particularly good at this. So, to equity and excellence, I could almost add access. Everyone should have access to the best PD [professional development], everyone should have access to the best principals and the best teachers. This is a real challenge, but it’s certainly part of what we’re trying to do.

As you’ve started to put this vision into effect — the teachers contract that has time for professional development, Learning Partners where schools can learn from each other — what kind of indicators are you looking at to see whether that’s working? And what are they showing you?

I think the 80 minutes [of weekly training time for teachers built into their latest contract] showed us that we need to do a lot more training of principals on how to get the most out of your time. I am personally doing a workshop Feb. 24 and 25 about maximizing resources: time, money, and power.

I’ve asked the deputy chancellors and myself at least once a month to go visit one of these 80 minutes to see how it works.

We have received an over 90 percent satisfaction from teachers on what they’re getting out of [the time], so that to me is particularly good. The 40 minutes for [teachers to engage with] parents is a little more of a struggle, a little bit more uneven. But here again, I go visit them to see what’s happening.

So feedback from people on the ground, from teachers and parents, about how things are going. Are there other indicators you’re looking at to see whether the changes you’ve made are having the effect you intended?

Certainly at the end of this year one of the things I’m going to be looking at very closely is teacher retention and principal retention. Are people looking to stay? Are people happy? You can’t have people working well if their morale is low.

I sent out a letter this week to all guidance counselors in the city thanking them for their efforts. I’ve gotten over 200 responses: “Thank you for thinking of us, no one ever says thank you, these are some of the things I’m doing in my school.” So that is really important. Guidance counselors are part of student achievement as well.

You know, New York City has multiple, multiple issues. I went to visit a school where I think 147 children are in a domestic violence shelter. That has an impact on the teaching in that building.

We’ve said the results will only be shown if we start supporting the parents and the teachers. Because if you’re a teacher and you’re coming into this situation every day, it’s not about just how you teach this kids, but how do you emotionally support them. So the results are crucial, but we need them to have support.

You have this agenda and teachers, in a lot of ways, seem to be responding well to it. But another role of the chancellor is to sell the public on that vision, and to enlist them in what you’re trying to do — to make clear what the agenda is and get them on board. Do you see that as an important part of your role? And how have you tried to do that?

Absolutely.

I’ve done over 50 town hall meetings. I do CECs [community education councils], CPACs [the chancellor’s parent advisory council]. I meet with the CEC presidents once a month on Saturdays, which is a big change, because I want to give them at least two hours of undivided attention. I answer all questions. Certainly when I went to Albany to do my testimony, one after the other said, I can’t believe you answered every question. You know every school.

So I will go speak to communities. [Partnership for New York City CEO] Kathy Wylde has come asked me to speak to the business community, I’ve done that. I’ve spoken at college commencements. I’ve met with several of our big funders. Microsoft is very happy with us. They just went to visit Thomas Edison High School, and said it’s the best CTE they’ve ever seen. And also, I do workshops for the City Council members, who are very crucial.

How would you describe your message when you go to these groups?

I think it’s, together we can make a difference.

One of the words I love is “reformers.” I’m a reformer too, but I just think I use different tools to reform.

[As a superintendent,] I had Park Slope, but I also had Red Hook, I had Sunset Park with a lot of English language learners, I had Crown Heights, and I had Bed Stuy — I had it all. But those principals had never talked to each other. I had 154 schools in that superintendency, and we created sister schools. I took every school that was in the top tier and partnered them with a school in the middle tier or the bottom tier, knowing full well that everybody had something to learn no matter where you were on these tiers.

So reform, to me, is making sure you have the best people doing the hardest work to raise student achievement. But they can’t do it without training, and whether the training is for the principal, for the teacher, for the borough directors. Training is everything.

Since you’ve been chancellor, can you see areas where tangible gains have been made?

Our results show it: better graduation rates, better reading scores moving in the right direction, more willingness of people to go out of their way for professional development. There was a time when people wouldn’t show up. We had a workshop recently on technology and 1,000 teachers showed up.

I’ve put out something called P Notes [a newsletter for principals] every month. I just got an email from one of the principals to thank me for having listed him in the P Notes. He never realized the power of P Notes, because he’s gotten five different phone calls from other principals who now want to know, can they come and visit and see what I complimented him on. So he said, “Thank you, Carmen, because usually my school would not be one that other people would see as an example.”

When you’re celebrated by your peers, that’s very energizing. I want to see more energy in our schools. I don’t want to see people beaten down.

You were talking about superintendents and how they fit into your vision. It’s come up recently with [principals union president] Ernie Logan [who said that principals of struggling schools now have a “shocking lack” of autonomy]. How do you balance having a clear chain of command versus principals wanting to have flexibility and autonomy? Logan said that’s become a challenge, and I’ve heard from some principals who feel like they’re seeing more compliance work and being pulled out of their schools more often. So how do you see that balance?

I think it all depends what people are complaining about. I think there’s a lot of areas where they’re still autonomous. They hire their own teachers, they certainly plan their own PD. I don’t put out blanket statements that every Monday must look like this.

I think on other issues — how many special-ed kids do you accept, do you accept English language learners — [principals are] not autonomous. We need to have equity, and if we’re going to have equity, everyone has to do their fair share.

If you are a [low-performing school in the “Renewal” program] or a school where you have struggling kids, you have less autonomy. Then you have a school where you’re a host Learning Partner. All our host Learning Partner schools are pretty much autonomous.

I keep saying to Ernie, if they complain to you, then all they need to do is complain to me and we’ll take it one issue at a time. I don’t think you have an overwhelming number of people doing this.

But I do think one of the things we need — we need an equity system. And you’re not going to have it if the principals in the Bronx can do certain things differently than the principals in Park Slope.

There’s always going to be a tension. I think total autonomy sometimes doesn’t serve kids, it serves adults. And that’s something [former schools Chancellor] Joel [Klein] used to say all the time: We’re in this business to work for kids, they are our clients.

And that’s how I look at it now. It’s all about the kids, it’s what happens in the classroom.