One student said he was suspended from AP English after an argument with a teacher. Another, a new immigrant from the Philippines, said he feared getting suspended for a minor “mistake.” And a third pointed out that metal detectors and school safety officers were the first things many students see when they walk into school.

These were just a few of the students who spoke at an education department hearing Monday night meant to vet public opinion on proposed changes to the discipline code, including the city’s recently announced ban on suspensions for students in grades K-2. The changes are part of Mayor de Blasio’s push to reduce suspension and implement “restorative” discipline practices, such as conflict mediation and counseling.

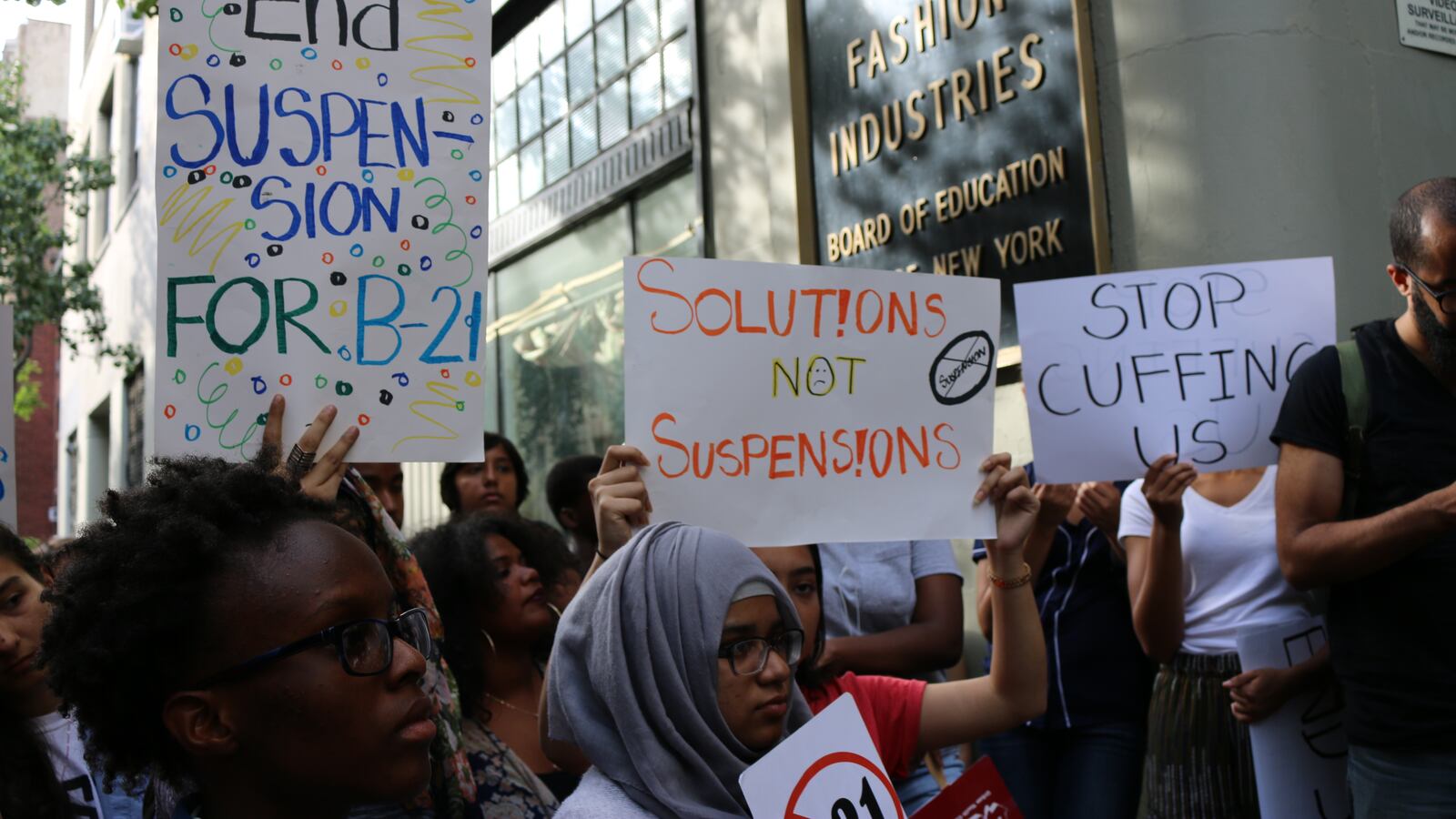

The students, many of whom were part of the Urban Youth Collaborative or other youth advocacy groups, filed into long auditorium rows, wearing matching t-shirts with slogans like “Our Bronx. Our Lives. Our Solutions.” They brought posters with messages such as “Stop cuffing us,” and took turns sharing personal stories during a boisterous public comment period.

“Our dreams and our goals…do not stop in third grade,” said one student at the hearing, referring to the fact that the proposed suspension ban ends after second grade.

At the top of students’ wish list of reforms is banning suspensions for ambiguous infractions, such as defying authority. While the city already made it more difficult to hand out these suspensions by requiring written approval to do so, some student advocates want the penalty removed altogether.

They say the policy leaves wiggle room that is disproportionately used to penalize black and Hispanic students for minor offenses.

“Because we are black, because we are girls, we don’t fit people’s expectations of what a girl’s supposed to act like,” said Zaire Kiran, a rising tenth-grade student at Nelson Mandela School for Social Justice in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. “People think that we will never graduate, that we will drop out and have a child.”

Other speakers voiced the opposite concern — that the city’s suspension ban went too far.

“Banning suspensions doesn’t eliminate the problem. Rather, an ill-conceived ban, combined with a lack of oversight of the current system and no real plan to move forward, will perpetuate an environment of chaos and instability that can undermine the success of the classroom teacher and the achievement of every student in his or her class,” said Richard Mantell, vice president of the United Federation of Teachers, echoing concerns raised by UFT President Michael Mulgrew.

But most of the adults who spoke seemed to side with the students. They noted that the ban on suspending young students has a loophole: it allows suspensions for students in grades K-2 who have a firearm or who are “substantially disruptive” and have been removed from class before.

“The administration represented eliminating suspensions for K-2 as a bold step towards disrupting the school-to-prison pipeline,” said Kesi Foster, a coordinator at the Urban Youth Collaborative in an email Tuesday morning. “After yesterday, we’re not sure it’s a step at all.”