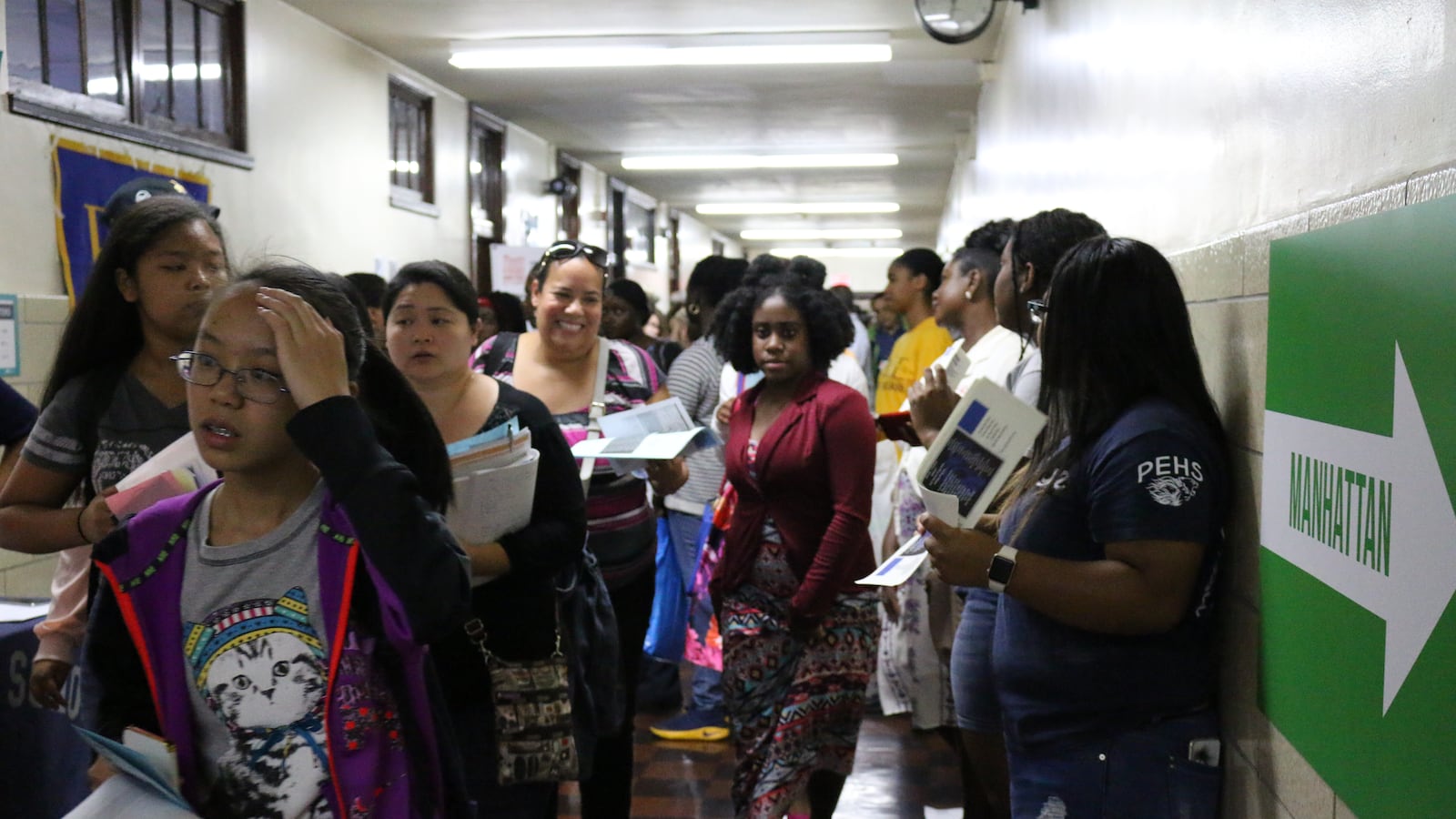

At 9:30 a.m. on a Saturday morning, the line to enter the citywide high school fair snaked around the corner. Parents waiting with their eighth-graders outside Brooklyn Technical High School, where it was held, joked that it was like waiting in line at a Taylor Swift concert.

“I’m ready to do battle,” said Brenda Wilson, the mother of an eighth-grader from Queens, as she and her son inched toward the door.

Spread over seven floors, the massive annual fair is supposed to offer students applying for a high school a glimpse of their options, a crucial opportunity since the city’s choice system means any eighth-grader can apply to any high school.

Every year, families attend in droves to learn about schools — and because the fair can improve their odds of getting in. Hundreds of high schools grant priority to students who demonstrate their interest, and visiting a school’s table at the fair is one way to do so, according to the Department of Education.

There’s just one problem: Many of the schools don’t seem to know the policy — or to follow it.

Chalkbeat spent two days at the fair this September and found school representatives who were unaware of the fair’s intended role in admissions and were, in turn, misinforming families. And the Department of Education does little to monitor whether schools are following the rules.

“I think it’s becoming, unfortunately, more of the norm,” said Maurice Frumkin, a former city education department official who now runs an admissions consultancy. “It’s very disappointing and, I think, unfair.”

This type of confusion helps perpetuate inequities that plague the entire high school admissions process. Families with the savvy to navigate a hazy system, and the time to advocate in multiple ways for their child, have an advantage. Families without that savvy — even those following the city’s stated policies — are often at a big disadvantage.

Showing your interest

Just over half of the city’s roughly 440 high schools have what are called “limited unscreened” programs, which are not allowed to admit students based on factors like their middle-school grades or attendance. There’s only one way students can increase their chances: Demonstrating interest in the school.

One way to do that is by attending an open house at the school itself. But attending open houses can be burdensome for families. Some take place during weekdays, for instance, forcing students to miss school or parents to miss work.

With that in mind, the Department of Education offers an alternative: Students can gain the same leg up by signing in at a school’s table at the citywide fair.

But many schools are not following that rule. Chalkbeat talked to eight school representatives at the fair — including guidance counselors, teachers, and school administrators — who said students who attended open houses at their schools were given preference for admission over those who attended the high school fair.

Some said signing in at a high school fair did not count toward admission at all. Others, when pressed, said their schools give priority status to open-house attendees first, then backfill with students on the high school fair list if there is extra room. (Chalkbeat checked with some of these schools after the fair, and they again confirmed that only students who attend open houses get top priority.)

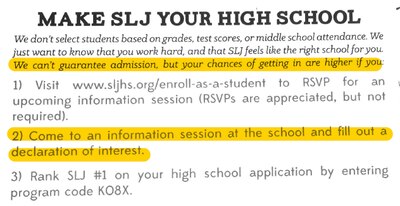

On one corner of the floor for Brooklyn schools, social worker Debby Wallace said it “does not make any sense” to give preference to students who sign in at Urban Assembly School for Law and Justice’s table. So many students sign in, she said, it might not be a real gauge of enthusiasm. “You could come here and sign in and not be that interested,” Wallace said.

Instead, students should attend an open house to show interest, according to a school brochure, and fill out a “declaration of interest” while there.

Wallace is articulating a paradox for schools. Students signing in at the fair may be genuinely interested in a school and unable to attend an open house, or they might be passing by with no real interest at all.

If limited unscreened schools stick to the rules, there is no way to judge which is which. Asking students to attend an open house helps them winnow down their applicants. And it’s understandable that these schools want to find a class of engaged students. They are already, in many cases, taking students who do not have the grades, attendance records, or test scores to get into one of the city’s top high schools.

“From the school’s standpoint, I understand where they’re coming from,” Frumkin said. “I suspect some schools feel that the fair is a waste of time, and other schools feel like even if we get signature at the fair, that’s not truly representative of student interest.”

Still, it’s kids without the extra support, or ability to navigate a system of confusing criteria, who will lose out. “I do think it’s disappointing,” he said, “regardless of the motives.”

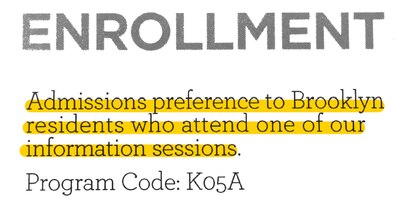

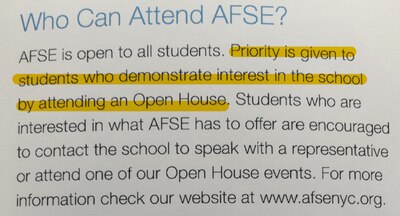

Many schools emphasize attending an open house in the brochures they hand to students and families.

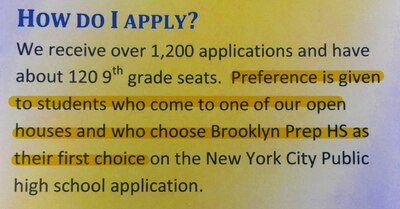

Brooklyn Preparatory High School’s brochure reads, “We receive over 1,200 applications and have about 120 ninth-grade seats. Preference is given to students who come to one of our open houses” on the high school application.

Gage Kearns, the ninth-grade counselor working the table at Brooklyn Preparatory High School, said the pamphlet means what it says.

“The only priority we give is for kids that go to the information session,” Kearns said, adding that the school is overwhelmed with signatures at the high school fair. He estimated that between 300 and 400 students signed up at the school’s table on Saturday.

Often, school representatives like Zoraida Torres-Rodriguez, parent coordinator at the Bronx School for Law and Finance, said the sign-in sheet was there just to collect contact information so schools could send information about upcoming open houses to families.

That attitude was so pervasive, some representatives assumed the practice was universal.

“To enter the lottery system, you have to sign up for an open house,” said Anna Lopez, a history and English teacher at Careers in Sports High School in the Bronx. “If any other school tells you otherwise, they’re lying.”

Policy vs. reality

What the schools say they are doing flies directly in the face of what the Department of Education says should be happening. According to the city’s policy, which was disseminated in a memo to schools before the fair, limited unscreened schools are required to offer the same priority to students who attend a citywide fair as to those who attend open houses.

Education department officials say the policy is clearly communicated to the schools and superintendents. But the department does not monitor what the schools actually do. Instead, enforcement happens on an ad hoc basis, when the department learns about a school that isn’t following the rules.

“We’ve taken concrete steps to improve and expand opportunities for schools and families to learn about high schools – including the new NYC School Finder [an interactive database], increasing the availability of translated materials, and ongoing work with schools and superintendents so they can support students and families,” said education department spokesman Will Mantell.

“We recognize the high school admissions process can be challenging for families, and we’re committed to making continued improvements based on ongoing conversations with students, families, and school staff,” he said. There are also boroughwide fairs one weekend in October where students can sign in and should be able to get the same priority, but the citywide fair is the only weekend all the schools are in one place.

Frumkin said despite the city’s efforts, the problem is a perennial one.

“There’s always been a disconnect from the central DOE and the school level,” he said. “While it’s easy to say every school has to do it this way, the reality on the ground may be different.”

In black and white

Part of the issue may be that the language in the Department of Education’s own high school directory is unclear.

At the beginning of the directory, it says certain schools give priority for students who sign in at high school fairs. Yet on the pages of those individual schools, it lists only the percentage of offers that went to students who attended an information session, without clarifying that “information session” can mean either an open house or attending the high school fair.

Department of Education officials said the full policy is shortened to “information session” on individual schools’ pages, but that it includes students who signed in at a high school fair. But families and school officials Chalkbeat spoke with understandably interpreted the phrase “information session” to mean they needed to attend an open house at a school.

Mary Lamont, the parent of an eighth-grader from Queens, said she did her research and realized some schools require open-house attendance.

“This whole thing is extremely stressful,” Lamont said. “We’ve got to go through this and set up a calendar [for open houses].” When she heard the Department of Education said signing in at a high school fair should offer the same priority, she was confused.

“That’s not what it says in the book,” she said.

She was not the only person who drew that conclusion. Natalie Cazeau, a counselor at the Urban Assembly School for Criminal Justice, who worked the high school fair table, said the same thing. Sometimes, they may look at the high school fair list if they need more students, but students who attend an open house get priority over those who sign in at the fair because that’s the official rule, she said.

“If you look in the book, it says you must attend an open house,” Cazeau said.

The city recently made its high school directory interactive for students and families, in an effort to make the search process easier and clearer, officials said. But the language about information sessions didn’t change.

Schools that skip the fair

Meanwhile, there’s a more fundamental problem at work: Many high schools don’t even attend the fair. Schools aren’t required to attend, and only 62 percent did this year, according to the Department of Education. (That includes limited unscreened schools and those with other admissions methods.)

Even when schools do show up and students manage to sign in, that doesn’t guarantee that their preference gets logged. Angella Grant, a guidance counselor at the Academy for Health Careers in Brooklyn, said she often has trouble reading the names of families who sign in.

“Sometimes it’s not legible when the kids write it,” Grant said. “This is like a madhouse.”

The principal of Urban Assembly Maker Academy, Luke Bauer, said he “could never read anyone’s handwriting,” so he switched to letting students sign in on an iPad.

Department of Education officials said schools are responsible for running their own sign-ins at the high school fair, and that they will continue to look for ways to make the process easier for families.

Yet beyond the letter reminding schools to count sign-ins at high school fairs as demonstrated interest, the DOE does little to enforce its policy. Schools are trusted to input the students’ names. That lack of oversight gives them little incentive to follow the rules.

Sharice Joseph, who has an eighth-grade son and lives in Flatbush, said she noticed a greater emphasis on attending information sessions at this fair than when she went through the process with her older son years ago.

As a result, she planned to make sure her younger son attends open houses at any school that caught his eye.

“We don’t want to take any chances,” Joseph said.