One day last fall, Ruby Bromberg rushed to her computer and frantically began refreshing the page to see when Bard High School Early College — a high-performing public school in Manhattan — would post its open house registration. When the site went live, she clicked through as fast as she could and snagged a coveted seat.

It’s a good thing she moved so quickly.

When she arrived at the school’s open house, she learned the slots had filled up in less than 15 minutes — and the principal welcomed students by cracking a joke about it.

“Congrats, this open house is harder to get into than ‘Hamilton,’” the principal quipped to the room, recalled Ruby, now a rising ninth-grader at the High School of American Studies at Lehman College. Everyone laughed, she said.

Ruby knew to be at her computer to sign up at precisely the right time because her family paid $150 for a service called High School 411. The service sends email updates with information and reminders about coveted open house slots. Without it, the website says, “families are left in the dark and on their own.”

That’s exactly how many city students feel when they’re applying to high school, a process that starts with attending open houses, a crucial first step. In some cases, the information sessions count toward admission. In others, they provide key information about a competitive school. But getting to them requires time, resources and flexibility many families don’t have.

Students like Ruby, who can supplement the city’s confusing system with a private service like High School 411 and ample family support, are in the best position. Those without such help face a much greater challenge.

“This is a very opaque process,” said Rhea Wong, executive director of Breakthrough New York, a program that helps low-income students through the high school admissions process. “Though there’s this illusion of meritocracy, it certainly advantages those who know how to work the system.”

WHY DO OPEN HOUSES MATTER?

At many city schools, attending information sessions helps determine whether you get admitted. The roughly 231 high schools with what are known as “limited unscreened” programs cannot, under Department of Education rules, consider factors like a student’s grades, state test scores, or attendance record. But they can take into account whether he or she “demonstrated interest” by attending an information session or signing in at a high school fair.

There is a weekend-long citywide high school fair held in late September in Brooklyn, and individual borough fairs during one weekend in October. Students are supposed to be allowed to sign in at these fairs and have that counted as “demonstrated interest,” but critics say that not all schools attend the fairs, and there is no way to track whether those sign-ups count.

A Department of Education spokesman said limited unscreened schools input their own list of students who have signed in at both high school fairs and information sessions. He also said high schools are “encouraged” to present at the fairs, but did not say they are required to do so.

At the most competitive of the limited unscreened schools, getting priority is virtually essential. At Pace High School in Manhattan, for example, where there are 36 applicants per seat, 100% of admitted students attended an open house or school fair. The same is true for New Utrecht High School in Brooklyn, which has about 20 students vying for each seat in its law and government program.

At the 157 city schools with “screened” programs, the process is murkier. These schools can judge admissions based on a number of factors, including test scores, interviews and writing samples. Some screened schools do not weigh open-house attendance in admissions decisions, but others, including Manhattan Village Academy, which has 40 students vying for each seat, do include “demonstrated interest” in their selection criteria.

Even for those that don’t officially count student visits, a highly competitive open house process means some prospective students never get a chance to see the school.

“It’s a very disconcerting system. We are stretched to our limits. We can’t do more open houses than we are doing,” said the principal of Bard Manhattan, Michael Lerner, who said his schools host several packed open houses, but can’t accommodate all the students who are interested in attending. “We do the best we can, but it pains me every year.”

Parents who have attended information sessions describe them as extremely helpful. The tours give attendees a feel for the school and school staff are on hand to explain and clarify how to apply, said Meeta Gandhi, the mother of a rising eighth-grader who attended some open houses last spring.

She is also skeptical that schools claiming they don’t track open-house attendance fully ignore it. In fact, Gandhi said she got the opposite message at her screened school tours last spring.

“They would say, ‘Be sure to sign in. It helps us know that you were here,’” she said.

NAVIGATING THE MAZE

Going to open houses requires figuring out when and where they are — which can be a complicated and time-consuming task.

Details about information sessions are supposed to be compiled on the Department of Education’s online “Admissions Events Calendar,” introduced in 2015. But so far this year, the calendar is incomplete.

A Chalkbeat survey of 50 high schools spread over the five boroughs found that only 26 of the schools had listed information sessions on the calendar this year, despite the fact that schools were asked to submit the dates by July 14. A review of 50 “limited unscreened” schools, all of which consider open-house attendance in admissions, yielded only 19 information sessions.

The city recently extended the deadline for schools to submit their open-house dates until Sept. 9. That means more dates will be added throughout the fall, but that does not help families who want to plan ahead, or those without a computer at home. And the process is underway: Some of the information sessions are in early September or have already passed.

"Congrats, this open house is harder to get into than 'Hamilton.'"

Bard Manhattan Principal Michael Lerner

“We encourage students and families to visit citywide and borough-wide high school fairs, where they can learn more about hundreds of high school choices and receive priority in admissions by signing a particular school’s list,” said education department spokesman Will Mantell. “We’ll continue to work with families and educators to make the high school admissions process easier and more equitable.”

He added that the city will continue to work with schools to post and update their information. The Department of Education has also launched an email service to inform parents of key deadlines and resources. Plus, parents and students can sync their Google calendars to the DOE’s list of open houses.

But online innovations bypass a more basic tool still used by families: the New York City High School Directory, said Maurice Frumkin, a former city education department official who now runs an admissions consultancy. He pointed out that few if any open houses are listed in this year’s printed directory, though there have been far more in the past.

“In certain parts of the city, they have no idea [about open houses]. What they do know is they were given a directory to take home over the summer and that’s your bible,” Frumkin said. “That’s the true equalizer. Beyond that, a lot of it depends on how savvy your counselors are, how engaged your parents are, word of mouth.”

Even if the online calendar did contain all open house dates, it has another problem: Many people don’t know that it exists or question whether it is reliable.

"Though there’s this illusion of meritocracy, it certainly advantages those who know how to work the system."

Rhea Wong, executive director of Breakthrough New York

Wong of Breakthrough New York, whose job it is to help students through the process, had not heard of the tool. Elissa Stein, who runs the 411 service, sent the calendar to her listserv with a warning.

“It’s a lovely start, except that it’s incomplete,” she wrote. “So, I suggest taking this with a grain of salt and always double-check on things.”

In reality, finding out about open houses requires visiting a variety of individual school websites. Some of them aren’t posted in a timely fashion and require a call to the school. That leaves groups scrambling over the summer to put together makeshift calendars.

Wong said she put her interns to work compiling a calendar. The process took a “solid week of full-time work.” At the school’s suggestion, Gandhi and a group of parents at her middle school divided up the duties amongst themselves, with each parent taking responsibility for six schools.

The whole process is more challenging for those who don’t speak English fluently or who don’t have access to a computer, Wong said.

“Primarily, it’s really just a question of time and navigation,” she said. “If I am a family who may not necessarily have access to information, or have the skill set to do research or even the time to do research, that’s going to be a disadvantage for me.”

THE SIGN-UP RACE

Bard is not the only screened school with a competitive open house sign-up process. Other elite public schools, like Eleanor Roosevelt on the Upper East Side, also use an online registration system for school visits. That one went live in the middle of Labor Day weekend.

At Beacon, another selective public school in Manhattan, there is no registration before the actual day of the open house. For Ruby, that meant knowing to show up hours early to get a spot in line with a blanket and snacks.

In middle- and upper middle-class circles, these open house tricks and rules are well-known. Jo Goldfarb, whose daughter is a fifth-grade student from Park Slope, attended a high school information session at NYU this summer. She said she remembers the fall when some of her friends were going through the process.

“All my mom friends, I asked them out for drinks,” she said. “And they said no, they had to be online. They were all tied to their computers.”

Being on top of this information quickly, like Goldfarb’s friends, is essential. High School 411 founder Stein said that almost all of these online registrations will “sell out.” Even starting in eighth grade can be too late. At the recent information session at NYU, the majority of parents who came to learn about the process had children in seventh grade. Two had children in fifth grade.

To get a jump-start on the process — and to allow enough time to make it through a long list of schools — many parents start touring schools in the spring of their child’s seventh-grade year.

For some lower-income students, the process couldn’t be more different. Yahayra Colon, a current college freshman from Washington Heights, said she did not realize the importance of the process while she was going through it. She didn’t go to any open houses — let alone participate in the sign-up race at the more competitive schools.

Even though she was one of her middle school’s top students academically, she said, she didn’t pay much attention to the process.

“I was not super engaged,” Colon said. “I didn’t have the support to go visit these schools, to sit in at these schools.”

She ended up getting into the Academy for Software Engineering in Manhattan, which she had no interest in attending. So, she entered the second round of high school admissions and was accepted at the High School for Media and Communications, a relatively low-performing school that had a 56 percent graduation rate in 2015.

The school was so scary and disappointing to her that she left after less than three weeks and went to a Catholic school instead. Her mom, a single mother and social worker, started working a second job to pay for it. The process “broke my heart,” Colon said. She ultimately transferred again, and again, before graduating from Frederick Douglass Academy II in Harlem and starting at SUNY Oneonta this fall.

ARE WE THERE YET?

In the event that parents manage to figure out when information sessions are, snag a seat at the competitive ones, and map out a jam-packed fall schedule, there’s one more obstacle standing in their way: Actually getting there.

Many of the school visits are held on weekdays, during the day, so for many parents that means taking substantial time off work. Ruby’s mom took about 10 half-days off to tour open houses with her daughter last fall, she said. And she only has the flexibility to do so because she owns her own company.

Colon said her mother’s job as a social worker was one of the main reasons she never visited schools.

“She couldn’t leave work to take me to a high school to visit. There was no time to kill,” Colon said. “My mom had to support me and my sister. There are bills to pay.” Her father was not in the picture, she said.

To make matters worse for many students, open houses at the city’s most competitive schools that factor open-house attendance into admissions are mainly in Manhattan and the Bronx — a far distance to travel from outer boroughs like Queens and Staten Island.

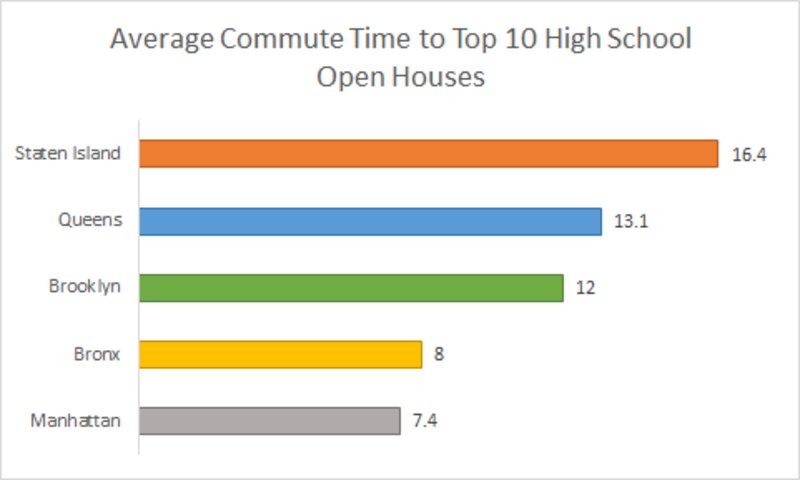

An analysis by Insideschools found that it could take a student leaving his or her middle school as long as 20 hours to reach the open houses at these competitive schools. Below you’ll find a breakdown of the average travel time by borough.

The most competitive limited unscreened school, Pace High School, is located on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, so it takes at least an hour to travel there from East New York or the Bronx, but less time from anywhere in Manhattan.

The most competitive screened school that considers open-house attendance in admissions, Manhattan Village Academy, is located in Midtown. As of last year, it required students to come with an an adult — an added hardship for students whose parents work.

The combination of hurdles limits the choices of some students and makes life difficult for others. That’s why Stein decided to help some parents through the process by starting her business.

“They call it a choice system, but in many ways it’s not,” Stein said. “There’s this illusion as to what this system is, but the reality is very different.”