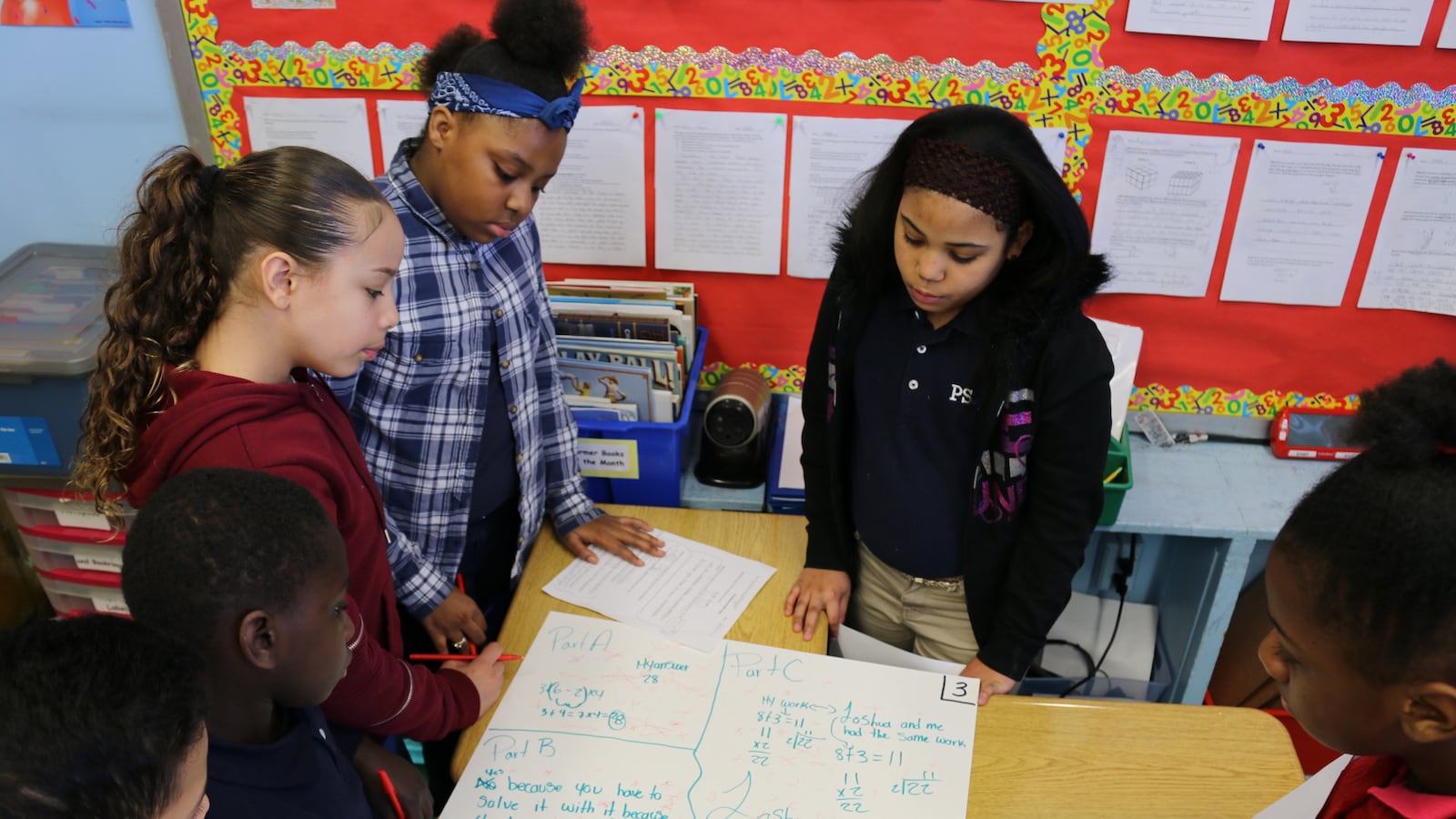

Fifth-grader Darmairys Henriquez used a green marker to write her answer to a math problem on a big poster board. Her classmates at P.S. 294 stopped by in small gaggles to take a look at her work.

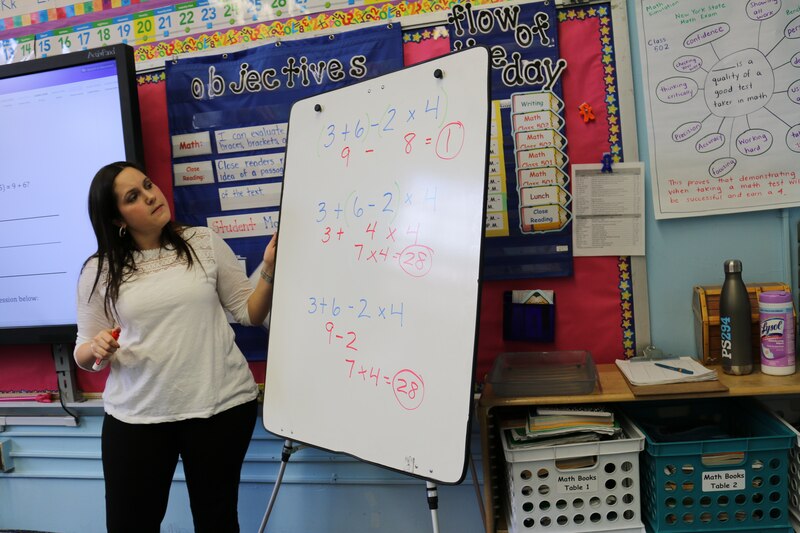

The question: 3 + 6 – 2 x 4.

The students were learning how to use grouping and the order of operations to solve a math equation, but it would be at least 30 minutes before teacher Nicole Lent would stand in front of the class and reveal the answer.

This approach is part of a citywide effort to make sure all students pass algebra by the end of ninth grade — paving the way for college and high-demand careers.

In 67 elementary schools across the city, including P.S. 294, fifth-grade math instruction has been “departmentalized” just like in middle or high school. Instead of sticking with the same classroom teacher for every subject — reading, writing, math and science — students have a teacher responsible only for math instruction.

The idea behind the city’s Algebra for All initiative is to have the most dedicated and effective teachers focus on this critical subject area, an approach backed by research.

“There’s still a lot of anxiety among elementary teachers about teaching math, and they still cling to the textbook,” said Clara Hemphill, who coauthored a report about math anxiety for the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs. “One way to break through that is for an elementary school to pick a teacher who really loves math and [have him or her] teach all the students in fifth grade.”

With a solid foundation in elementary school, the city hopes students will be ready to tackle math in middle school — and higher-level courses such as calculus in high school.

“It is a building block for college readiness,” said Matt Larson, president of National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

P.S. 294 in the Bronx has embraced the model, with specialized math teachers in not just fifth grade, but starting in third grade. One teacher serves as a coach for her fellow math instructors, allowing the strongest teachers to share what works and problem-solve when lessons go wrong.

Along with departmentalization, P.S. 294 launched a whole new way of teaching math, using a method that encourages students to engage in discussions the same way they might debate literary themes in a book club.

“In a lot of schools, literacy takes the forefront,” said Principal Daniel Russo. “What we do here is try to build the strongest, most inquisitive, abstract mathematicians we can.”

First, students try a problem on their own, and then debate it with their classmates, defending their answers or changing their minds entirely based on the input of their peers.

With her classmates gathered around, Darmairys began her defense: “So what I did was I added,” she said, describing her approach. She added parentheses around one part of the equation so it read 3 + (6-2) x 4.

“I got a total of 28,” she said. “I’m ready for questions and comments.”

That was the cue for her classmates to jump in. A boy who came to a different answer — 1 — was the first to speak up.

“You were supposed to just get 1, because you didn’t really need parentheses,” he said. “I thought it was just simple. You were just supposed to add.”

Lent had been floating around the room with a clipboard, but now she stopped by Darmairys’s group to listen in. She asked a few leading questions, like “Do I really need parentheses?” But Lent stopped short of providing any answers, even when her students came up with wrong responses. (The answer, by the way, was 1).

Instead, the students were left to explore the possible solutions and methods together. Eventually, one boy noticed his classmates came to different conclusions depending on where they placed their parentheses in the equation.

From the outside, Lent’s teaching seemed largely invisible. But everything was carefully curated, from the type of problem students were asked to solve to the students who were asked to present their particular approaches.

“It’s a lot of thinking on your feet,” she said. “You’re always looking for what is going to bring the most discussion.”

Class had started with a problem that was intentionally different from anything they had seen before. Lent looked over their shoulders as they worked, marking on her clipboard groups of students who used different strategies to come to different conclusions. Next she chose students to present their work, picking those who had some parts correct but demonstrated different misconceptions.

Lent said this kind of teaching “did not happen overnight.” But she “always felt more comfortable” teaching math, and passionate about sharing it with students.

P.S. 294 was already using the model, along with “departmentalized” math teachers, when the city announced its Algebra for All initiative. The school joined the program to take advantage of extra training and resources. Teachers involved in Algebra for All receive at least 17 days of training, and P.S. 294 landed a city grant to pay for materials and professional development sessions tailored to the school’s needs after Lent noticed teachers needed help teaching fractions and algebra. Lent said the trainings were instrumental.

“It changed my way of thinking,” she said. “I always thought you had to teach the easiest way to just get an answer, and that is not the case. It really opened up my mind to thinking about the how and why.”

P.S. 294 overhauled its math instruction three years ago and “departmentalized” last year for the first time. Their first round of test results suggest the new approach is paying off.

In Lent’s class, 23 percent of students have a disability, 35 percent are current or former English Language Learners and 29 percent live in temporary housing. Another 19 percent have repeated a grade.

Yet the school’s students outperformed city and district averages on last year’s state math tests, with 53 percent of students passing, compared with 40 percent across the city. Students who are learning English — typically among the lowest-performing subgroup — improved their scores by 9 percentage points.

In the high-stakes environment that schools operate under, Russo hopes schools like his will encourage other principals to try new approaches to math. He understands the pressures well: P.S. 294 opened in the place of a school that was phased-out after struggling for more than a decade.

“If I don’t know for sure that this model is going to push my scores and my children, I’m afraid to try it, because I have so much to lose,” he said. “I think that when the Algebra for All schools come out with some data that’s trending a little bit stronger, that will pique the interest of more schools.”

Russo admits it takes the right teachers and leaders to make an approach like theirs work. The Department of Education has made departmentalization optional at elementary schools. So far, about 400 teachers across the city have gotten professional training to encourage the same kind of strategies that are in place at P.S. 294.

“We’re really focused on helping teachers understand the content and giving teachers … strategies to teach the content,” said Carol Mosesson-Teig, senior director of mathematics for the department. “We want to make sure that kids have a sense that they belong they belong in the math classroom.”