As students settle into their AP chemistry class, the teacher gets through some housekeeping announcements in English and then switches to Mandarin to begin the day’s lesson.

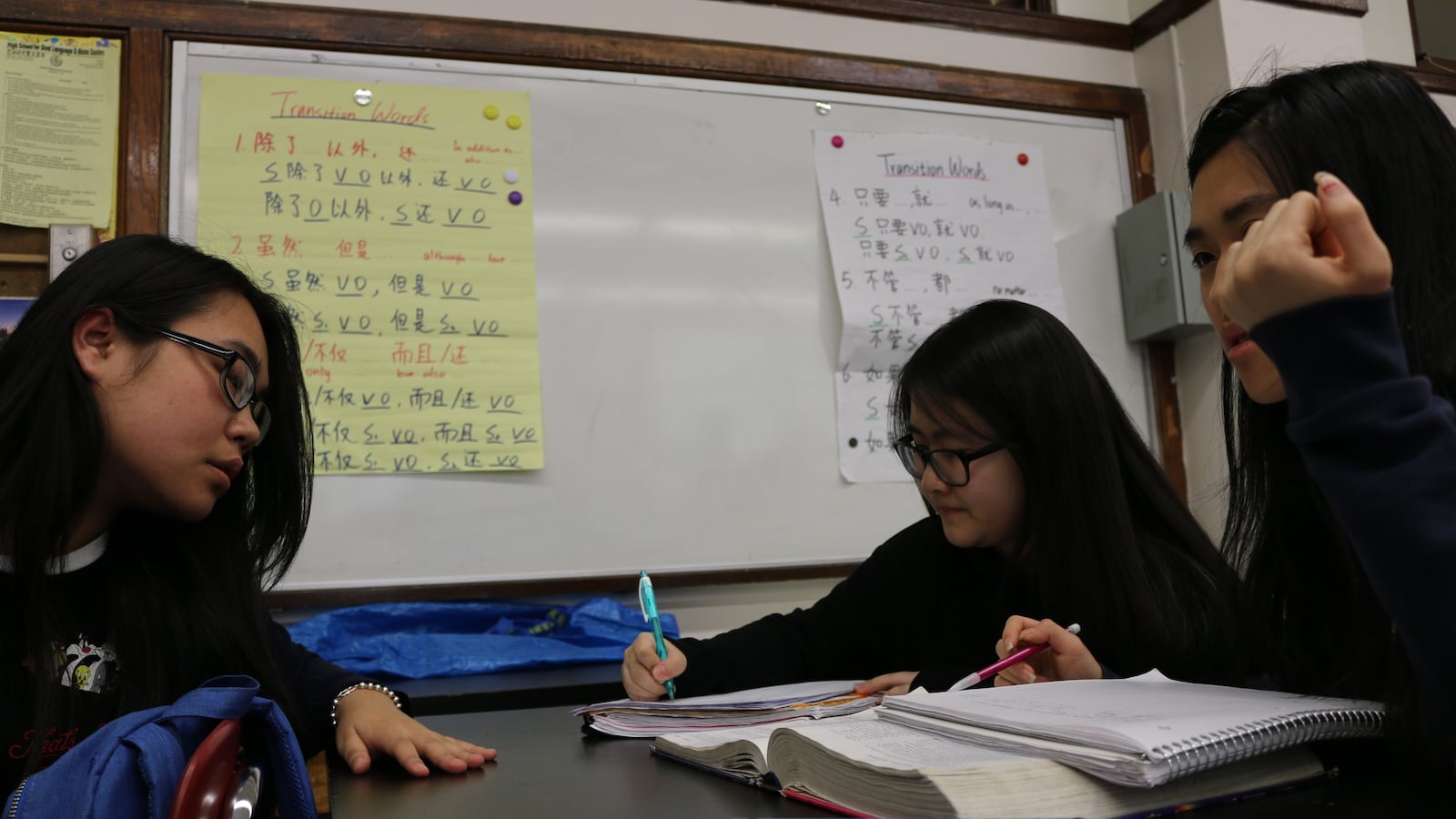

The class is taught in both languages, to a group of students made up mostly of current or former English Language Learners — as is their school, High School for Dual Language and Asian Studies on the Lower East Side.

Principal Li Yan says that challenging courses like this college-level class are one of the key reasons students at his school do so well. Less than 51 percent of current and former English Language Learners graduated citywide last year, far below the city average of about 73 percent. At Dual Language high school, where roughly 80 percent of students are current or former English learners, almost every senior earned a diploma last year.

“You can’t automatically assume they can’t do things. They can,” Yan said. “You have to have high expectations.”

About 13 percent of New York City’s 1.1 million students are considered English learners — a group of students that can be among the toughest to serve. Last year, while the dropout rate for the city overall declined, the dropout rate among English learners jumped to 27 percent — an increase of more than 5 percentage points from the year before.

But Dual Language high school and a handful of other schools across the city manage to buck that trend, providing valuable lessons for how to better serve these students.

For instance, Dual Language high school tries to enroll a healthy mix of native English and Chinese speakers to make the dual-language model work. Dual-language schools split instruction into two languages, so math class may be taught in English one day and in Mandarin the next.

Asian students in New York City are already more likely to graduate than their peers. But Dual Language high school pays special attention to make sure English learners don’t get caught in red tape that could keep them from earning a diploma. The school’s program is set up so students can move easily to higher-level English courses, even mid-year, rather than getting stuck in classes their language skills have outgrown. Schedules are constantly monitored and changed to meet students’ needs.

“This is important,” Yan said. “You can’t get to senior year and say, ‘This kid needs five English classes.’”

In research circles, dual-language programs are often singled out as a highly effective way to teach English while also allowing students to maintain their native language.

In New York City, however, a group of schools has shown remarkable success using a different approach.

The Internationals Network for Public Schools is a nonprofit that helps run more than a dozen schools in New York City, catering exclusively to recently arrived immigrant students. Last year, its schools’ average graduation rate was 74 percent, according to Director Joe Luft. That’s higher than the citywide rate for all students.

Students at Internationals schools learn both subject content and English in the same classes in what’s called an “integrated” model. The teachers work together across subjects to make sure students learn the vocabulary they need before conducting a science experiment or taking on a new math concept.

“Language and content are inseparable,” Luft said. “You need to teach them real high school content. You can’t wait until they know enough English to do that. You have to do both simultaneously.”

Group work and projects are also core to the network’s teaching strategy. Students are deliberately mixed based on grade level and individual strengths, ensuring they have as many opportunities as possible to practice their language skills and learn from each other.

They are encouraged to communicate the best way they can — even if that means speaking in their native language. Though it might seem counterintuitive, letting students draw on their existing language to express themselves and understand classroom commands or content is actually an effective strategy, said Miriam Eisenstein Ebsworth, a director in New York University Steinhardt’s division of Multilingual Multicultural Studies.

“If you stick somebody in a total immersion situation, how would you know what’s going on?” she asked. “It’s traumatic, it’s unhelpful and it really slows them down.”

Internationals Network schools focus only on the needs of English learners. But Robert F. Kennedy Community High School in Queens is proof that a typical high school can also serve these students well.

Robert F. Kennedy is an “educational option” school, meaning it intentionally admits students across a range of academic abilities. As a result, the student body is closely aligned with the demographics of the city as a whole. Eleven percent of the students are English learners, and among them are Spanish, Chinese and Arabic speakers. Eighty-six percent of its current or former English learners graduated last year.

Like Internationals schools, Robert F. Kennedy uses integrated instruction, where English language and content are taught side by side. The school puts an emphasis on including English learners in sports, clubs and school celebrations.

“They need to feel part of the community,” said Maria Toskos, an assistant principal who helps oversee services for English learners at the school.

Robert F. Kennedy has been able to avoid problems that plague other schools statewide. State rules, enacted last year, require that teachers in integrated settings either be certified in language instruction, or work as a co-teacher with a colleague who has the credential.

But there are consistently language teacher shortages. Co-teaching is costly and requires teachers to work together closely — and well.

But Robert F. Kennedy has a stable of dual-certified teachers. In co-teaching cases, before teaching assignments are made, Barbetta said he asks teachers for their placement preferences — and the school makes an effort to honor those requests.

“There’s really buy-in,” said Principal Anthony Barbetta. “We’re fortunate.”

New York City has come under scrutiny for how well it serves English learners, and recently announced it will open 68 new language programs. The city hopes to have every English learner in a bilingual program by 2018.

Still, people who work with English learners or study their progress say better data is needed to help more students make it to graduation. Some advocates objected recently when Chancellor Carmen Fariña seemed to downplay the city’s role in that process.

Ebsworth, the NYU professor, said it’s hard to predict who will earn a diploma and who won’t. Each English learner is unique: Some come from their countries with a solid academic foundation, others come with little or no formal schooling. They may have some experience with the English language, or none at all.

To better understand how to serve them, experts want to learn more about those who don’t graduate. Are they stumbling on specific exams? Are students with less formal schooling more likely to drop out? What role does a family’s economic needs play?

“We can’t tell what the outcomes are being influenced by,” she said. “There’s a big problem with the data.”