There are stars showing student performance on tests, bar graphs displaying school funding, pie charts revealing teacher experience.

The colorful pages released Monday by New York state officials are an illustration of how the state could display information about schools to the public. Creating a “dashboard” is part of the state’s broad rethinking of what it means to be a successful school under the new federal education law.

State officials stressed that this is only an illustration of what it could look like and it’s very much a work in progress. They are not required to submit the “dashboard” with their final plan, which is required by September under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act — so they have some time. Still, the early glance provides clues about the state’s approach.

The state’s new dashboard reflects its desire to avoid a narrow focus on test scores and instead provide several different measures of whether a school is succeeding or needs to improve. Under ESSA, dashboards can include virtually any statistic, including comparisons among similar students, suspension rates or factors such as school funding and teacher experience.

The main drawback of dashboards is that they can be confusing. Between bar graphs, scatter plots and rating systems, they can make it difficult for parents or the public to draw simple conclusions — or even understand the information — about their own schools, critics argue.

So far, the head of the state’s Parent Teacher Association said these dashboard mock-ups are a good sign, but there is more to discuss.

“Overall, this would be a step in the right direction,” said Kyle Belokopitsky, its executive director. “The sample may need revisions so parents can fully understand the content.”

Here are the mock-ups provided Monday, which the state cautioned are early drafts and would not be finalized without parental input.

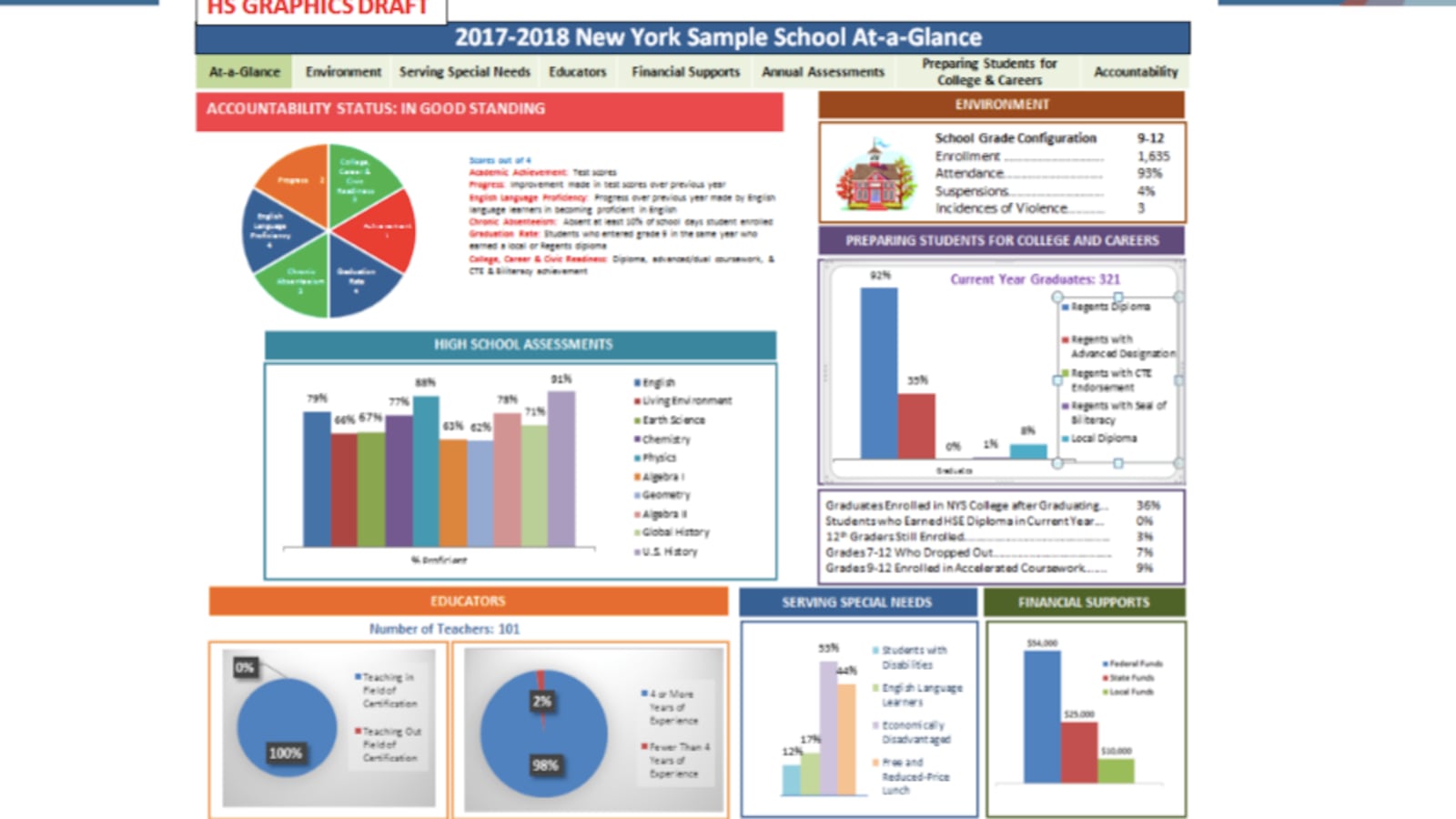

Sample “School-At-A-Glance”:

The one-page snapshot includes information about whether students have completed advanced coursework, such as passing Algebra II or graduating with an Advanced Regents diploma. It also has information about test scores and graduation rates, but comparisons — at least on the draft — occur only in a 1-4 rating system based on a formula that determines how a school compares to others in the state.

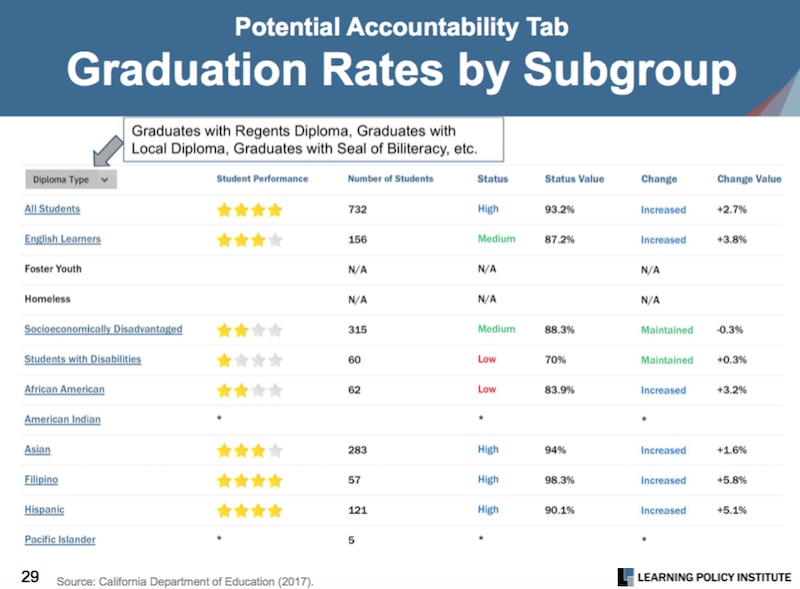

Sample “Report Card Dashboard”:

This more detailed draft report uses one to four stars to show how schools compare to other schools statewide, both as a whole and in terms of how they serve particular subgroups, including African-American students, Hispanic students or English language learners. The “subgroup” idea has already generated some controversy, with critics arguing it sets lower expectations for some groups of students and could be confusing for parents.

The more information the state provides, the more complicated the dashboard can get — and that garnered some apprehension from observers.

“I hope they’ll be clear about how these school report card stats were generated,” tweeted Bobson Wong, a teacher at a large public high school in Queens. “Lots of hidden info in there.”

State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia said the state will work with parents to ensure it is easy to understand.

“We’re going to be working with groups of parents,” Elia said. “That will all be part of a process to gather what it is we really need to include and when we include it, what’s the best way to include it so that it’s transparent.”

The dashboards also give the state a chance to experiment with “equity” indicators. Some of the sample measures included in the mock-ups include the ratio of guidance counselors to students, access to specific classes, or level of integration.

Taking a more careful look at “inputs” like these is in line with the direction the Regents have been headed under Chancellor Betty Rosa’s leadership: away from evaluating schools based on student test scores and toward an approach that tries to assess whether their students had access to a quality education. In an interview with Chalkbeat earlier this year, Rosa explained her theory of improving schools.

“Just because you raise the bar [does not mean] the student can jump over that bar without building the steps to get them there,” Rosa said. “For me, it’s more important to build those steps.”