New York state projected that 23,000 students could receive the state’s new Excelsior scholarship, reducing their in-state tuition to zero.

The number of students who applied, according to numbers released last month? 75,000.

The wide gulf raises questions about whether New York adequately informed students about the scholarship’s detailed requirements — and whether some students might wind up losing their scholarships or having them turn into loans as a result.

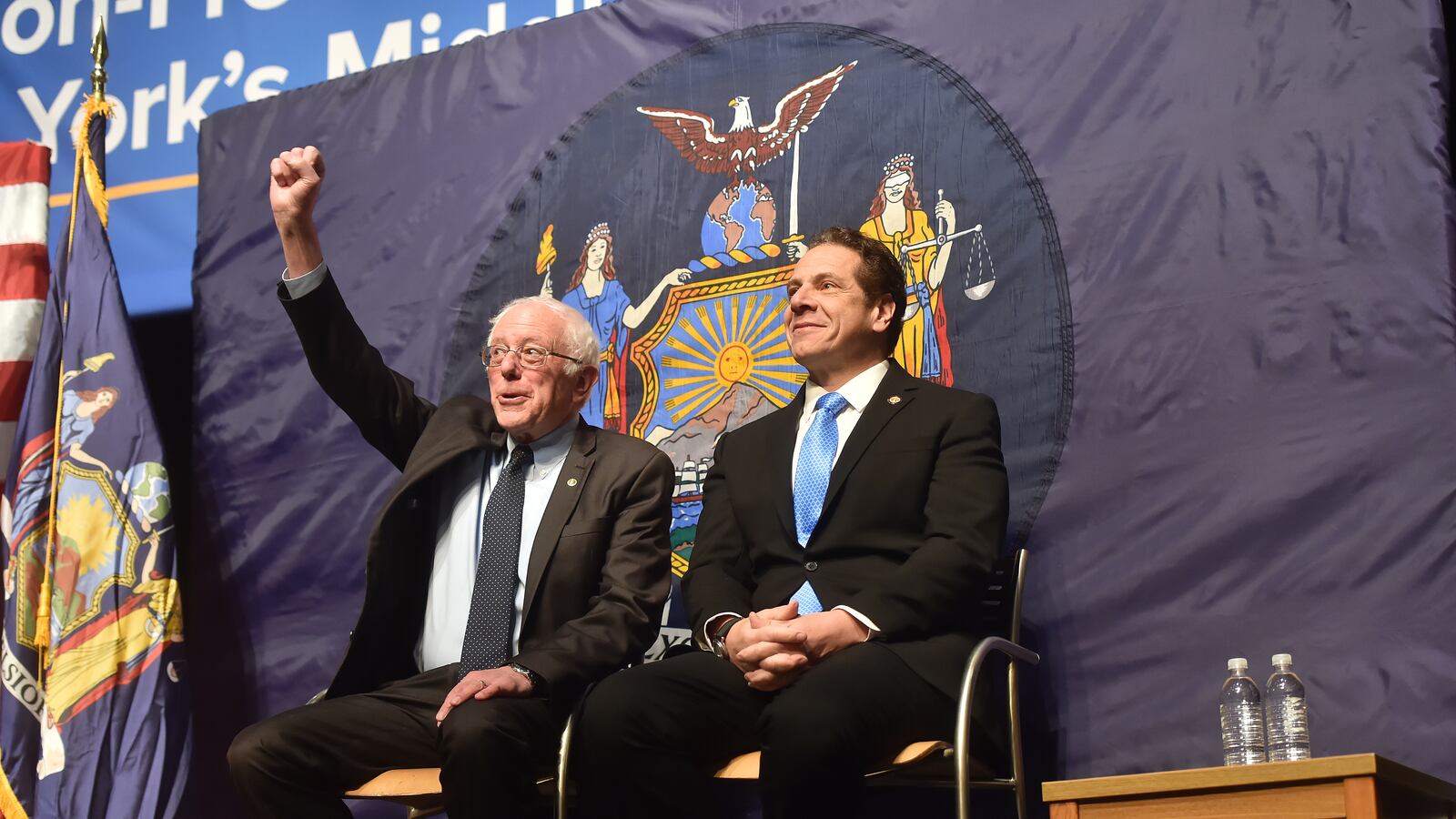

Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the program with great fanfare in January. But when the bill was signed, the fine print became clear: Students are required to attend school full-time to keep their scholarships, and stay in New York after graduating for the same number of years as they received them, or reimburse the state for their schooling.

Sabrina Green, a junior at Hunter College, heard about the scholarship at school and read about it in newspapers. She was excited, she said, and confident she would qualify based on her family’s income — but her application was rejected.

“I had no idea that the number of credits from my previous semesters would affect my chances of recieving the scholarship,” she said in an email. “I don’t think I was adequately informed about the qualifications.”

At Borough of Manhattan Community College, nearly a thousand students applied for the scholarship, according to the director of financial aid Ralph Buxton, even though the vast majority of students do not graduate on time or already get enough state and federal financial aid to cover tuition.

“We may start out with a couple hundred this semester and lose them second semester,” Buxton said. “I would say that everybody that’s applying has no firm idea about what the performance requirements are and will not be able to meet them.”

As the scholarship gets off the ground, state officials must decide how much to build the buzz, and how much to emphasize the rules.

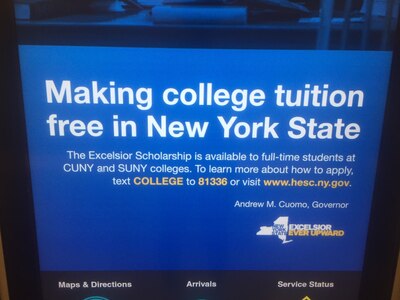

So far, the state has worked to advertise free tuition — but the requirements are not always front and center. Subway ads advertise “Making college tuition free” with little detail. On the state’s website, the requirement to stay in-state after graduation or have the scholarship converted to a loan is not mentioned until the last section on the “Frequently Asked Questions” page.

At the same time, a letter sent to every junior and senior who took the SAT and PSAT clearly states the residency requirement to live and work in New York state after graduation. And the state is holding workshops with guidance counselors and asking students to sign a contract that outlines each requirement before accepting the scholarship.

“There’s no intentionality in not leading with the requirements. What there is is the big point — you can go to college tuition-free,” said a Cuomo administration official. “Like anything else, there are requirements. We’re not hiding or shying away from any of this.”

Getting the balance right is important. For students like the ones at BMCC, the main cost of not getting, or even losing, the scholarship might be a blow to their resolve or ability to get through college.

But other students who are seduced by the free-college advertising could wind up making a deal that could later put them deep into debt.

“Fine print on a scholarship is kind of scary,” said Sara Goldrick-Rab, an expert on college affordability and a professor at Temple University.

She points to Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education, or TEACH, a federal grant program aimed at encouraging aspiring teachers to enter high-needs subject areas and schools. But, like Excelsior, it places restrictions on the jobs that prospective teachers can take once they leave school — and making other choices leads to sudden-onset student loans.

About a third of TEACH grant recipients have had their grants converted to loans, according to a 2015 Government Accountability Office report. Sometimes, the report found, the loss stemmed from a misunderstanding of the grant terms.

Understanding the fine print of college scholarship programs is a problem nationwide, said Martha Kanter, executive director of the College Promise Campaign.

“Part of the challenge of a college promise — any college promise — is understanding who’s eligible, what are the persistence requirements, what are the consequences if you don’t persist,” Kanter said. “Understanding all of that when you’re 18 years old is a huge leap.”