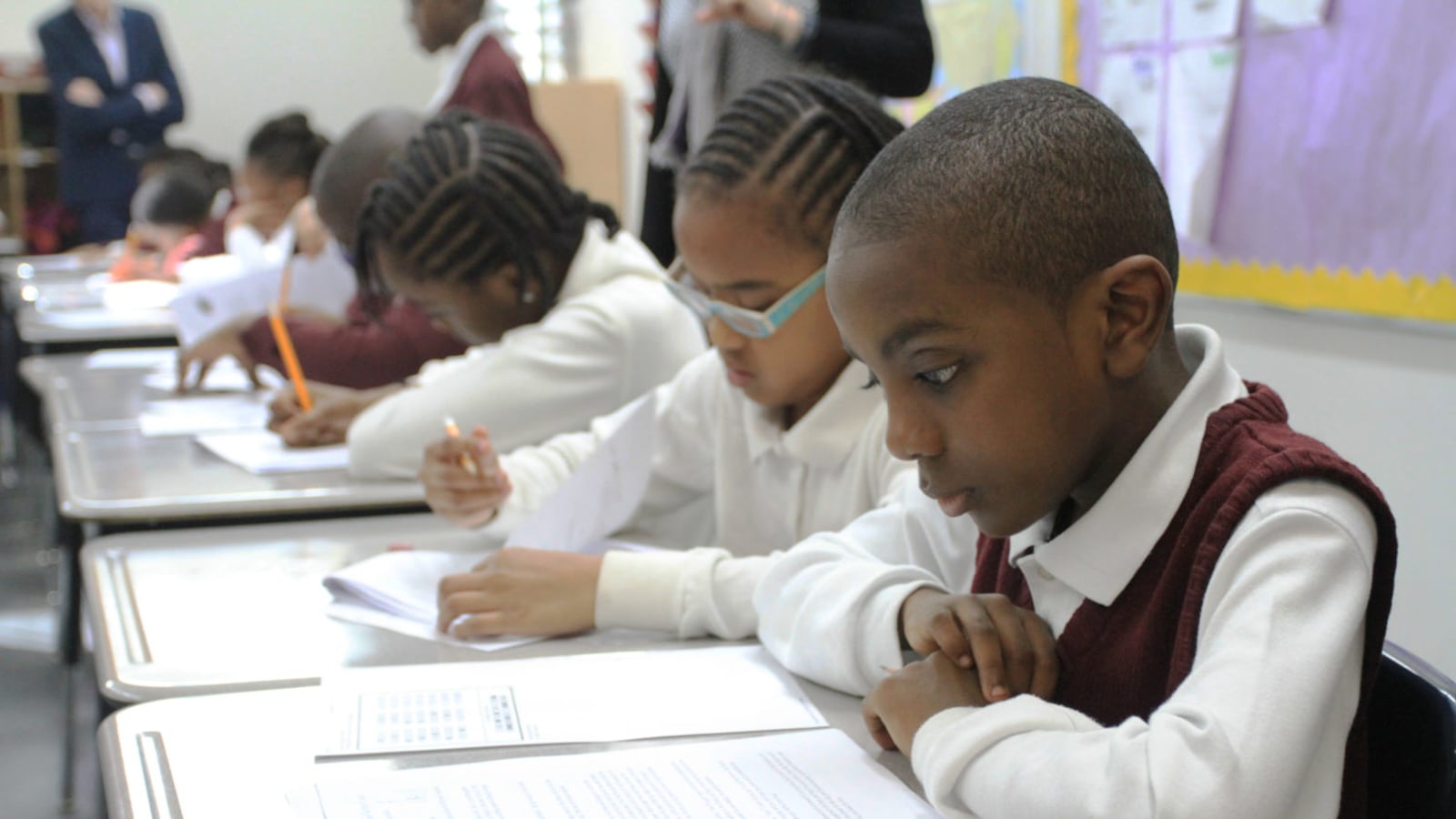

Recently, Dawn Brooks DeCosta, the principal of a traditional elementary school in Harlem, was looking for way to boost her students’ social and emotional skills. Her search led her to an unlikely event: a charter school assembly.

She watched as students at the Bronx Lighthouse Charter School publicly shared life updates. Some had lost a tooth, others celebrated a birthday, still others were earning A’s in math. Later, students competed to put the scattered lines of a poem back in order.

There was “a lot of cheering, a lot of excitement,” said DeCosta, the principal of Thurgood Marshall Academy Lower School. She was so impressed she decided to replicate the assembly at her school once a month.

“If it’s really good,” she said, “maybe we can do it twice.”

DeCosta was introduced to Bronx Lighthouse through the city’s District-Charter Partnership program, a city initiative kicked off in 2015 that brings together schools from both sectors to share ideas on topics ranging from classroom discipline to working with families to improving teaching.

While the political clashes between the charter sector and Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration often grab headlines, behind the scenes there is a growing collaboration that — contrary to de Blasio’s occasional critiques of charter schools — his administration is trying to nurture.

“While there remain real policy disagreements,” said James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center, “there is also a very positive attempt to work across them or around them.”

For de Blasio, the program may serve as an olive branch to the charter sector, and allow him to show his concern for all students — no matter the type of school they attend. For the charter sector, it’s a chance to learn from traditional schools while also sharing their innovations, which many consider a core purpose of charter schools.

“At the end of the day,” said Jane Martinez Dowling, head of programs for KIPP NYC, “we want all of our students to rise together.”

A growing number of schools are participating in the city’s district-charter partnership. This year, 36 schools are joining the program. And this past summer — through the program — 25 rising seniors from three district high schools took part in the KIPP charter network’s Through College Summer Bridge initiative, where they learned about the social, academic, and financial aspects of college life.

Melissa Harris — the education department official tasked with overseeing the district-charter program — may be uniquely qualified for the job: Her daughter previously attended a Success Academy charter school and now attends a district school. (Harris said she switched schools because her daughter was interested in programs at the district school, not because of any problems with Success.)

Harris said that even though the political fights around charter schools attract the most attention, when it comes to actual schools, cooperation is the norm.

“When you hear about district and charters having tension, usually you hear about that on a very high level,” said Harris, the senior executive director of the education department’s Office of School Design and Charter Partnerships. “But once you get down to the ground, everyone’s working together.”

The partnership program has several components: Some are aimed at smoothing the relationship between schools that share the same building, while others are designed to get district and charter school leaders to share tips about math instruction, serving students who are still learning English, or adopting less-punitive discipline policies.

A program by Uncommon Schools — a network with 23 schools in New York City — has trained 172 district school educators last year, and 500 total, on everything from how to call on students to how to check if a student understands a problem.

Some of the partnerships sprang from the ground up, Harris said. For instance, the superintendent of Brooklyn’s District 16 organized a “crawl” across the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood that encourages parents to visit the local district and charter schools.

The program has also been helpful to independent charter schools, which cannot lean on the built-in support group of a charter-school network or a traditional district. Richard Berlin, a founding member of Harlem RBI’s DREAM Charter School, which has a large population of students with disabilities, said the partnership allowed the school to compare its special-education program to that of other schools.

“As a non-network charter, we’re always looking for partners we can learn from,” Berlin said. “We have to create our own network.”

An indirect benefit of this collaboration is that it can break down charter and traditional school leaders’ preconceived notions about each other.

At the beginning of the partnership, principal DeCosta said she took part in an awkward conversation where she and some charter school leaders shared assumptions about each other. She told them she was under the impression they did not serve many students with disabilities, while they shared their negative perceptions of teachers unions.

“It was uncomfortable,” De Costa said. However, “It definitely did shift my perspective.”

Despite the ground-level collaboration, political battles continue — with most revolving around school space. Charter leaders have long argued that the de Blasio administration has made it unnecessarily difficult for charter schools to get space, while the administration argues that it is a complicated and inherently timely process.

Recently, it appeared the charter sector and de Blasio were headed for a truce after the mayor struck a deal with lawmakers this summer in exchange for their extending his control of the city’s schools. It included providing MetroCards to charter school students and streamlining the process for finding or paying for space for charter schools.

Yet, even after the deal, the charter sector is still demanding school space for this year and insisting that de Blasio hasn’t held up his end of the bargain.

Though Harris wants to focus on the relationship-building aspect of her job, she is also charged with carrying out the deal and responding to schools’ questions — and complaints — about building space. That involves acting as a liaison to Success Academy, the city’s largest charter network and the one that’s been involved in the most high-profile clashes over space with the de Blasio administration.

Harris said she is doing her best to respond to Success’ space requests, but added that the city is required to get input from community members before making space decisions — and that takes time.

“We’re in constant conversation,” Harris said, referring to her office’s interactions with the charter sector. “So I don’t think that anyone can say that we’re not meeting, answering the telephone, trying to be as honest as we can about what we can do to support their organizations.”

This story has been updated to clarify that Uncommon Schools trained 172 district school educators last year.