William came to the United States as a child more than a decade ago, and still remembers his first impressions of New York City: towering buildings, modern cars, a jumble of cultures on the crowded sidewalks.

Now 19, he grew up in a remote indigenous village in the mountains of southern Ecuador, where he had limited schooling. His parents emigrated to New York when he was a baby, leaving him with family and friends until he was in elementary school and they could afford to send for him.

“My thought of coming to America was getting a chance to see what was beyond the mountains,” he recalled. “But also finally meeting my parents and living with them.”

William is one of more than 30,000 New Yorkers who benefit from Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the Obama-era program for young undocumented immigrants now slated for termination by the Trump administration. His life, like those of many in the program, was thrown into turmoil by Tuesday’s announcement.

William was less than two weeks into his freshman year at a local CUNY college when he heard the news from a fellow student in his international studies class. “I completely lost focus the entire day,” he said. “I was literally crying and having an anxiety attack.”

The DACA decision felt like a betrayal by the president, he said, and reminded him that his future in this country is not assured.

“I’ve grown up here. My friends are here. I consider myself American,” he said. “I don’t know what I would do if I were to be sent back to Ecuador. I’ve lost touch with the culture. I’ve lost most of my family over there.”

William, an only child whose father installs floors and mother is a personal trainer, describes his early years in New York City as a mixture of excitement and fear. He remembers once riding the subway and accidentally sneezing on a police officer. Unable to apologize in English, he stood there mutely, staring up at the angry cop until his mother realized what had happened and spoke on his behalf.

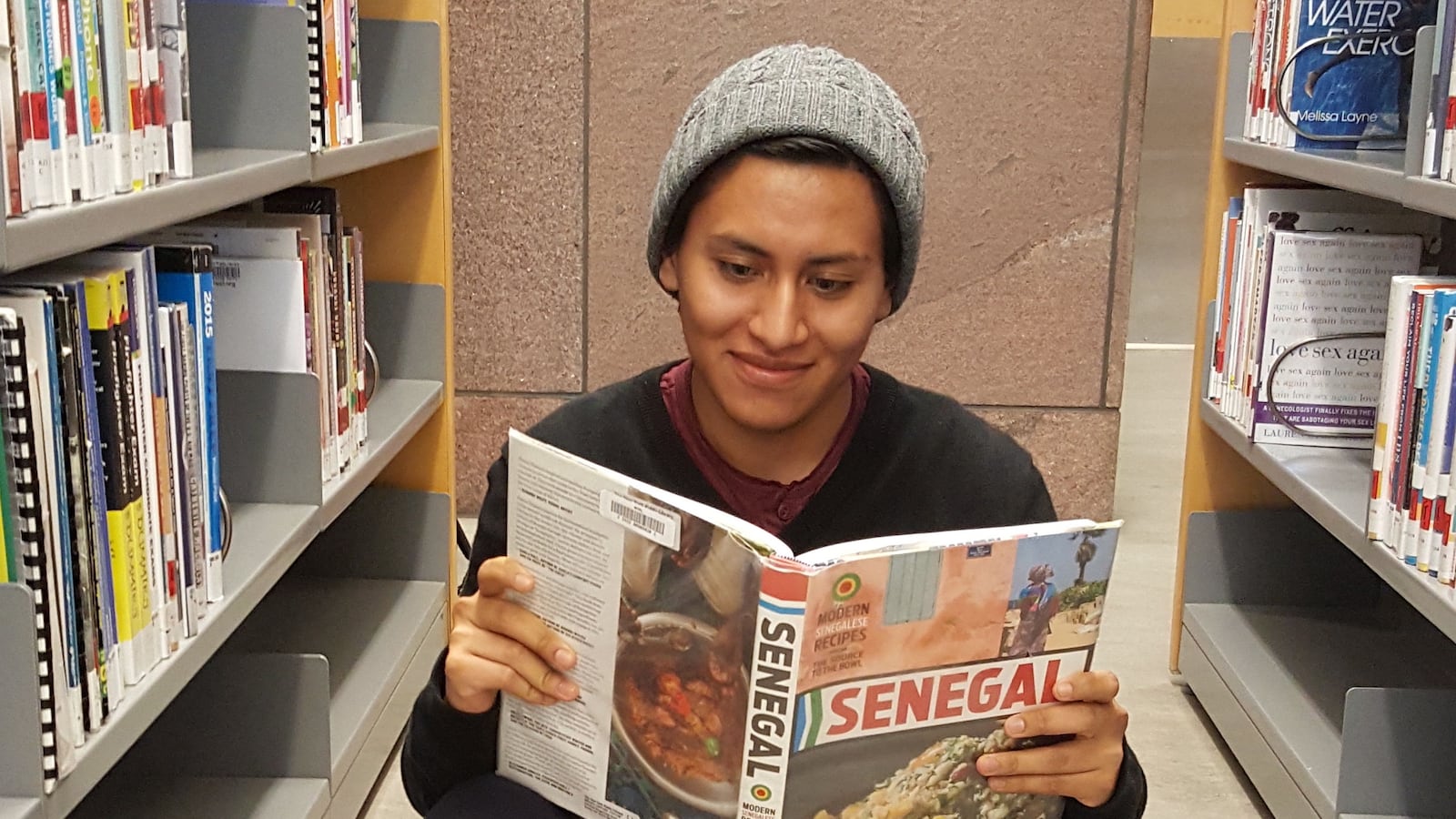

Since her own English was still rudimentary, she sent William to a public library in Queens most days after school, where he was tutored by teenagers and practiced his English with the librarians. His mother suggested that he attend the storytime for younger children so he could hear how words were pronounced.

“I didn’t want to go because there were younger kids who would sit there, literally toddlers,” he said. “Sometimes when they would see me sitting there for storytime, they would laugh.” He felt awful, he said, but it paid off; he was soon fluent in English.

His mother also made sure he didn’t settle for his local high school, pushing him to look beyond his home borough for school. He ended up at Beacon, a selective high school in Hell’s Kitchen. Now aware of his undocumented status, he shared it with people who could help him apply to college — his guidance counselor, for instance — and a nonprofit called Sponsors for Educational Opportunity.

“I’d been hiding my identity for such a long time,” he said. “At that moment, starting to reveal my true self was kind of frightening.”

DACA status — which he first received four years ago and will have for nearly two more years under the current guidelines — proved essential. It gave him a social security number, allowing him to get a state I.D. and learner’s permit, apply for a credit card, and find a part-time job at a supermarket. It’s “helped me kind of blend into my American life,” he said.

But it doesn’t open every door. Even with DACA, he explained, can’t study abroad or participate in certain internships. “My classmates have opportunities I don’t have,” he said. “Whenever I think about that, my world kind of breaks down because there’s so many things I’d like to do.”

The fear that fell over him Tuesday was tempered in part by a visit to his college’s immigration center, where he was advised not to panic. For now, his plans to become a diplomat or lawyer are still on track. His DACA status is secure until it expires and his college scholarship through a program for Dreamers is safe for now.

With questions still swirling about the future, he said, the staff at the immigration center was mostly providing emotional support. “They told me that I’m not alone,” William said. “There’s so many other people who are also experiencing the same thing.”

Correction: This story has been updated with William’s mother’s current job.