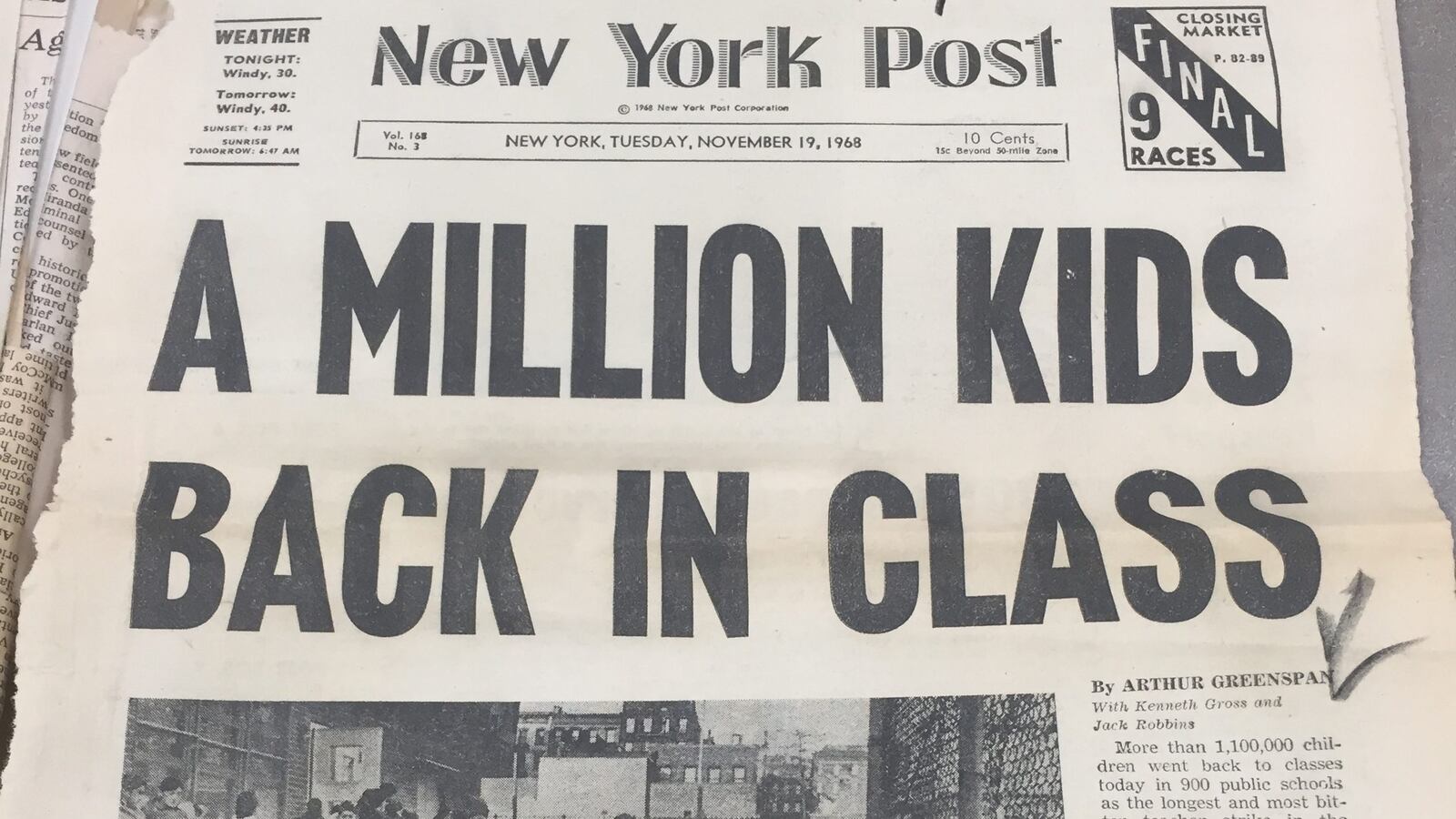

Fifty years ago this fall, the United Federation of Teachers went on strike three times, closing New York City public schools for more than six weeks. The legacy of these strikes continues to reverberate through the city’s schools today.

As Monica Disare detailed in Chalkbeat, the strike was sparked by a telegram in May from the black and Puerto Rican leadership of the Ocean-Hill Brownsville Demonstration District, one of three experiments in “community control” of schools created by the Board of Education. The telegram informed 19 teachers and administrators — 18 white, 1 black — that their employment in the district had been “terminated.” The district’s leaders believed that they had the power to make these decisions. The union believed the action violated their guarantee of due process.

By the fall, the conflict in Brooklyn had engulfed the city. Nearly 57,000 teachers walked picket lines, and over 1 million students were out of school.

New Yorkers have battled over school governance for more than two centuries, and the struggle continues in ongoing debates over mayoral control. The 1968 conflict, however, did not simply transform the school system. It reshaped political alliances, social movements, and labor organizing in the city for decades to come.

The Board of Education abandoned the community control experiment one year after the strikes, but the school system was decentralized by the state legislature into quasi-independent districts with elected community school boards in 1970. This system, in turn, was eliminated in 2002 at the request of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who won control of the city’s schools from the state legislature.

This centralization has not gone unchallenged. Parents regularly demand more democracy and transparency from the city, and state lawmakers now reconsider mayoral control nearly annually. Fifty years on, many of the questions that New Yorkers struggled with in 1968 remain urgent and unresolved.

Who will teach the city’s children and how will they do it? How will the city address persistent racism, segregation, and educational inequality in its schools? Who will be held accountable to the children and parents schools serve, as well as to the teachers employed by the system?

The Gotham Center for New York City History, in partnership with Chalkbeat, asked eight historians and scholars of education to reflect on how this history remains relevant for New York City public schools today. Here’s what they told us.

Clarence Taylor: The strikes are a reminder that Black and Latino parents have sought control for generations — Read More

Richard Kahlenberg: The strikes paved a path for charters — and away from integration — Read More

Jonna Perrillo: Then and now, teachers need popular support to win rights and respect — Read More

Heather Lewis: It’s difficult to make change from the top down. Grassroots activists should lead the way — Read More

Steve Brier: Community control opened CUNY to the people. Maybe it’s time to revisit the idea — Read More

Robyn Spencer and Mary Phillips: Students today are curious about Black Power — Read More

Nelson Flores: Schools are still dealing with the assumption that they alone can solve poverty — Read More

Sonia Lee: Will Asian Americans join the broader civil-rights struggle? — Read More

The strikes are a reminder that Black and Latino parents have sought control for generations

By Clarence Taylor

The 1968 New York City strikes were just one episode in a long history of conflict between black and Latino parents and a school system that prioritized protecting the interests of those who ran the system over properly educating black and brown children.

In 1956, twelve years before the strikes, the Board of Education created a commission to recommend ways to integrate the school system. One year later, a sub-committee recommended that the board transfer experienced teachers to schools on an involuntary basis to ensure that schools in black and Latino communities were not assigned the least experienced teachers.

The New York Teachers Guild, the organization that became the United Federation of Teachers in 1960, campaigned against the policy. In an article titled “Integration Yes! Forced Rotation No!” Charles Cogen, president of the Guild (and later president of the American Federation of Teachers), claimed such a plan would lead to a “transient teaching staff,” lower the quality of education, and antagonize staff whose good will was essential for implementing integration. Cogen argued that “difficult schools” were not a “racial problem.”

Civil rights and civic groups attacked the Guild’s position. The Intergroup Committee on New York City Public Schools, which represented 26 organizations, publicly denounced the Guild’s opposition to the transfer plan. Nonetheless, transfers were never implemented, and the question of whether the city’s black and Latino children will receive the same educational resources as white children — including teachers — persists today.

The Guild’s actions also undermine a major argument among some scholars and commentators, who have argued that the Black Power movement was responsible for the crisis. That contention ignores this earlier history of conflict between teachers and black and Latino activists and parents.

Community control, like the fight for school integration, was an attempt to redefine the relationships in a school system that had marginalized black and Latino parents. Parents wanted to have decision-making power when it came to educating their children. They still do.

Clarence Taylor is a professor emeritus of history at Baruch College, CUNY. He is the author of “Knocking at Our Own Door: Milton A. Galamison and the Struggle to Integrate New York City Schools” and “Reds at the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights, and the New York City Teachers Union.” A longer version of this essay appeared online for Jacobin in September.

The strikes paved a path for charters — and away from integration

By Richard Kahlenberg

When I interviewed people for my 2007 biography of teacher union leader Albert Shanker, no topic raised more intense emotions than the 1968 teacher strikes. They spawned a civil war among New York City liberals, one which continues to be fought over issues such as charter schools, school segregation, and the role of teacher unions.

From the beginning, Shanker had concerns about Mayor John Lindsay’s idea to create a separate school governance structure in Ocean Hill-Brownsville. Shanker marched in Selma with Martin Luther King Jr., and he questioned whether community control of segregated schools – even with the intent of empowering black educators — would provide genuine opportunity for black youth.

Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, architects of King’s 1963 March on Washington, fully supported Shanker’s strikes. Rustin further suggested it was a mistake to embrace segregation, even when the schools would be run by black people.

Today, despite overwhelming evidence that segregated schools are bad for students and that unions provide a valuable voice for educators, the inheritors of the community control movement continue to push nonunionized and segregated charter schools. Ironically, Shanker helped launch the charter movement in 1988 by suggesting the creation of new schools that would be teacher-led, unionized, and economically and racially integrated. But most charter schools today claim that unions are the problem and that segregation doesn’t matter. Thankfully, there are a small number of charter schools — what my colleague Halley Potter and I call “smarter charters” — that are faithful to Shanker’s vision.

Outside the charter debate, liberal opinion continues to diverge on the importance of addressing segregation, even within Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration. The mayor’s first chancellor, Carmen Fariña, at one point suggested that students in segregated schools become “pen pals.”

Fortunately, the new chancellor, Richard Carranza, says it is time for change. Somewhere, Rustin and Shanker are smiling.

Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, is author of “Tough Liberal: Albert Shanker and the Battles Over Schools, Unions, Race, and Democracy” and the coauthor (with Halley Potter) of “A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charters and Public Education.”

Then and now, teachers need popular support to win rights and respect

By Jonna Perrillo

Fifty years ago, teachers shut down the city’s schools in a battle over curricula, student discipline procedures, and teacher hiring and tenure policies. The walkout became one of the most memorable strikes in our nation’s history.

This spring, as the Janus case worked its way through the Supreme Court, teachers again caught the public’s attention, staging mass walkouts in five states.

Unlike in the 1960s, union leadership was not at the forefront of the 2018 walkouts. Instead, everyday teachers gathered in state capitols, striking against state education boards and elected officials rather than community stakeholders. These walkouts look almost nothing like the UFT’s 1968 strikes. But contemporary strikes are still connected to the past, raising fundamental questions about professional authority and expertise.

In 1968, teachers believed they deserved uncompromised say over educational decisions. Organized black and Puerto Rican parents, galvanized by an achievement and discipline gap that teachers appeared to exacerbate, disagreed. Teachers won the political battle but they lost public empathy. They were seen by many city residents to be racist, unprofessional, and driven by self-gain. By breaking apart tenuous partnerships between schools and communities during the strikes, teachers made their challenges more profound and success less likely.

Today, too, teachers need to maintain a broad coalition of supporters to advocate for themselves and a range of other conditions — material and political — that make good schools work.

The protests this spring offered unexpected hope. Reports of teachers’ salaries in rural states shocked many Americans. We learned that many districts have adopted four-day school schedules to cut costs. We were appalled by images of broken, aged textbooks that teachers posted on social media. Altogether, the strikes reminded us that undervaluing of teachers is always intimately tied to undervaluing of disenfranchised students and public education itself.

Jonna Perrillo is an education historian and associate professor of English education at the University of Texas at El Paso. She is the author of “Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equity.”

It’s difficult to make change from the top down. Grassroots activists should lead the way

By Heather Lewis

Half a century ago, activists in New York City’s community control movement fought for quality schooling in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Bedford Stuyvesant, the Lower East Side, Harlem, and the South Bronx. Today, these neighborhoods and their schools have changed significantly. However, poor and working-class residents still suffer from unequal access to quality housing, healthcare, and schools.

For the city to break a 90-year pattern of unequal and segregated schooling, the history of the strikes remains relevant. Recognizing the leadership of grassroots activists remains essential.

The Department of Education and the United Federation of Teachers have not organized any commemorations of the events of 1968. For those who celebrate the history of the community-control movement, however, its legacies include the partial realization of black and Hispanic self-determination; the role of women leaders in fostering democratic participation; and the growth of bilingual and multicultural education. Movement activists established and served on locally elected school boards and fought for community access to quality health, housing, and daycare services.

Although the confrontation with the UFT led to the demise of the experimental school districts, activists attempted to keep their ideals alive during the decentralization period that followed. In some cases, their efforts contributed to the spread of bilingual schools and programs, middle school reform, and culturally relevant pedagogy. Their efforts belie the common perception that decentralized schooling was a failure in New York City.

As the mayor and chancellor today respond to calls to address the city’s segregated schools, the lack of historical analysis in the media contributes to calls for simplistic, top-down prescriptions for change. The mayor and chancellor will find it hard to reduce the city’s inequalities with such policies, just as their counterparts did in the 1950s and 60s.

The city’s leaders would be well-served to pay close attention to current grassroots organizers in underserved communities. As John Dewey argued, “The democratic road is the hard one to take … it is the road which places the greatest burden of responsibility on the greatest number of human beings.”

Heather Lewis is professor and acting chair of art and design education at Pratt Institute. She is the author of “New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and its Legacy.”

Community control opened CUNY to the people. Maybe it’s time to revisit the idea

By Stephen Brier

The question of who should control New York City’s schools today is largely a question of how long the occupant of Gracie Mansion will be allowed to play K-12 education’s top dog: one year or longer? The answer currently rests in the clutches of Republican state lawmakers who grudgingly dole out one year of mayoral control at a time.

But half a century ago, control of the city’s public schools was an all-consuming question, roiling the city and dividing thousands of parents of color from teachers and administrators who were predominantly white and Jewish.

The UFT, led by Albert Shanker, went out on strike in 1968, strangling newly-formed community control demonstration districts in their infancy. Set up in Harlem, Ocean Hill-Brownsville, and the Lower East Side, the districts were an experiment that gave parents elected to community governing boards a real say in how their neighborhood schools would operate.

Schools in those three communities remained open during the UFT’s strikes. They pioneered new curricula — black history and African culture being among the most important — as well as new, progressive approaches to teaching. Teachers in these schools abandoned the forced discipline and rote recitation that defined much of public schooling in New York City in the previous decades.

The community control struggles over K-12 schooling inspired other progressive education efforts in the city. Most notably, these included the successful struggle by college students of color and their white allies to force the Board of Higher Education at the City University of New York to implement open admissions for all city high school graduates. Open admissions, a wonderful expression of the idea of community control over education, opened wide access at CUNY to poor and working-class students — white, black, and Puerto Rican — who flocked in record numbers to CUNY in the years after 1970.

However, real community control of the city’s public schools and public university was never given a real chance to work, thanks both to Albert Shanker and to politicians and business leaders responding to the fiscal crisis of 1975. Maybe it’s time to revisit the idea.

Stephen Brier is a professor in the Urban Education PhD program and founder of the Graduate Center’s Interactive Technology & Pedagogy certificate program. He is the coauthor (with Michael Fabricant) of “Austerity Blues: Fighting for the Soul of Public Higher Education,” and is currently working on a study of the fight for community control over New York City’s K-16 public education system in the 1960s.

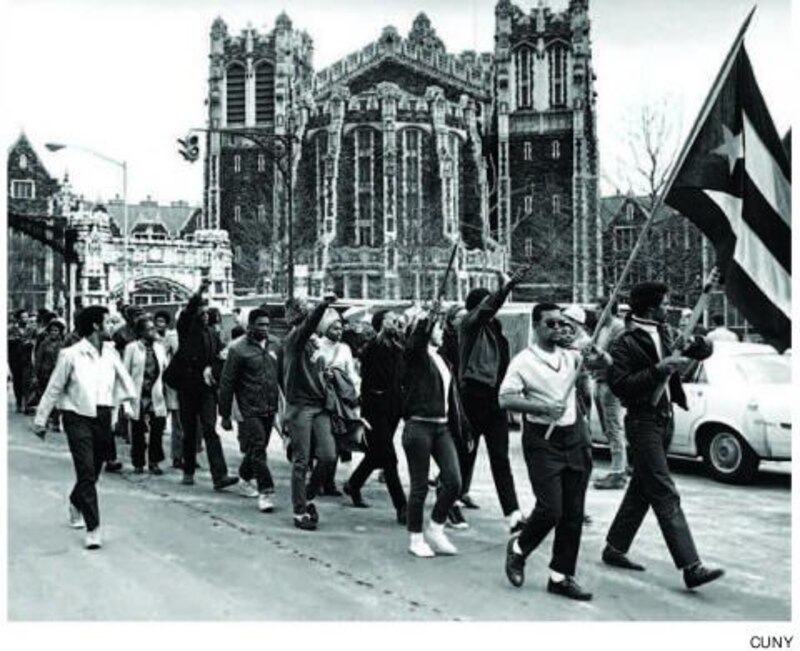

Students today are curious about Black Power

By Robyn C. Spencer and Mary Phillips

When a former Black Panther stood up to speak at CUNY’s Lehman College this spring — 52 years after the organization was founded and half a century since the global uprisings of 1968 led by students — the discussion that followed centered around the Panthers’ Oakland Community School.

Students wanted to know about its legacy. Was it akin to today’s charter schools? How did the school involve parents? What philosophies governed how it was run?

The community control movement was not limited to a single community in Brooklyn. The vision of community-controlled schools emerged from within the broader Black Power movement, in which the Black Panther Party was one of the most visible and influential organizations. The Party’s 10-point platform and program, released in 1967, sought the “power to determine the destiny of our black community” and asserted belief in “an educational system that will give to our people a knowledge of self.” The Black Panther Party, including local chapters in New York City, inspired community control activists and, in some cases, worked alongside them.

The dream of community-controlled education did not die with the “demonstration districts” in 1969, neither in Brooklyn nor across the nation. While some parents and educators sought to realize their goals in the new “decentralized” districts, others formed new independent schools. Again, the Black Panther Party led the way.

The speaker at Lehman College earlier this year was Ericka Huggins, who served as director of the school from 1973 to 1981. Oakland Community School was an elementary-level institution in Oakland, California that employed an activity-based learning model grounded in critical thinking and was informed by innovative practices such as yoga, meditation, and restorative justice. The school was a reflection of both the organization’s political vision and the practical needs of the community. Similar schools were opened by Black Power organizers across the country in these years, including the Uhuru Sasa Shule (“Freedom Now School,” in Swahili), which was founded by former Ocean Hill-Brownsville teacher and community activist Jitu Weusi (formerly Leslie Campbell) in Brooklyn.

Interest in Huggins is part of a reframing of the history of the Black Panther Party, which acknowledges the contributions of women leaders within the movement and grassroots initiatives like the community control struggle in New York City and the Oakland Community School. As founders of the Intersectional Black Panther History Project, we are committed to bringing these stories to the public.

Robyn C. Spencer is a historian of black social protest after World War II, urban and working-class radicalism, and gender. She is a co-founder of the Intersectional Black Panther Party History Project.

Mary Phillips is a proud native of Detroit, Michigan. She is a scholar-activist and public intellectual who works as an assistant professor in the department of Africana Studies at Lehman College, CUNY. She is a co-founder of the Intersectional Black Panther Party History Project.

Schools are still dealing with the assumption that they alone can solve poverty

By Nelson Flores

While the 1968 teacher strikes were primarily a black and white conflict, the first Puerto Rican principal in New York City was hired by the Ocean Hill-Brownsville governing board. In 1968, he had developed a bilingual education program to serve the sizeable Puerto Rican population that also resided in the community.

Bilingual education was lauded by community leaders, but a survey of local parents indicated that only 23 percent knew about the program. According to the survey, parents’ top three concerns about the community were housing and slums, robbery and vandalism, and addiction and dope. These challenges had less to do with schools than the overall effects of concentrated poverty and segregation.

A core assumption of the community control experiment was that addressing issues of school governance and curriculum would be sufficient to dismantle the impact of generations of racial oppression. But this assumption was deeply flawed. The board did not have the power or resources to reverse the hyper-segregation and concentrated poverty that afflicted the Ocean Hill-Brownsville community. Instead, its leaders of color were simply included in an existing power structure.

The rise of bilingual education demonstrates how this dynamic played out. As bilingual education became professionalized, it became removed from the day-to-day struggles of low-income immigrants. As a result, upwardly mobile community leaders were able to increase their professional standing while doing little to transform the lives of those relegated to segregated, high-poverty communities. One troubling lesson of Ocean Hill-Brownsville may be that the efforts of educators of color to transform the system may have instead contributed to, rather than relieved, the marginalization of the community’s residents.

Today, schools are still grappling with the unrealistic expectation that they can alone resolve the legacy of generations of racial oppression. Instead, programs like bilingual education should be seen as a complement to a much broader effort to reverse longstanding inequities.

Nelson Flores is an associate professor in educational linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education.

Do Asian Americans want to join the broader civil-rights struggle?

By Sonia Lee

The history of the community control movement in Ocean Hill-Brownsville is a reminder that creating a shared, culturally pluralistic humanity takes time and hard work – but it is possible. And this informs the current debate around admissions to New York City’s elite public high schools. At stake is more than the number of seats that will be assigned to Asian American, white, black, or Latino students.

Today, many Americans consider “blacks” and “Latinos” to be naturally unified as “people of color,” while Asian Americans stand outside this rainbow coalition as “ambiguous allies” or “honorary whites.” In the postwar era, however, African Americans and Puerto Ricans did not necessarily see each other as political allies.

This changed in the 1960s, when Puerto Rican parents decided that it would be more beneficial to join black parents’ fight to promote their children’s education than to pretend that their children were getting a fair education. By joining the school boycott of 1964 in large numbers, they publicized their political identification with African Americans in a highly visible way. And when the legislators sought to dismantle the Ocean Hill-Brownsville demonstration district, 55 Puerto Rican parents wrote to the city’s board of education, proclaiming that “Ocean Hill-Brownsville is the only place in the city of New York” where “something meaningful has been done for Puerto Rican children and Puerto Rican teachers.”

Puerto Rican parents and educators recognized that the civil rights struggle was not a narrow fight to protect the rights of African Americans exclusively, but a fight to build a society that would value all people.

Asian American New Yorkers who oppose Mayor de Blasio’s new proposal could argue that this history of black-Puerto Rican coalitions is irrelevant. But Asian American students face many of the same battles that black and Latino students do. The entire public school system suffers from underfunding, overcrowding, high turnover rates of teachers, and over-testing. Instead of fighting battles that advantage one group over another, Asian Americans would do better to forge a broad coalition of citizens who can demand a quality education for all young people.

Sonia Lee is an associate professor in the department of American Studies and Latino Studies Program at Indiana University. She is the author of “Building a Latino Civil Rights Movement: Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and the Pursuit of Racial Justice in New York City.”