Twelfth graders at the International Community High School in the South Bronx were pumped when they watched their social studies teacher, Alhassan Susso, receive the state’s Teacher of the Year award in September, the first time a New York City educator has received the honor in two decades.

When Susso’s name was announced, 18-year-old Eric Parache and his classmates watching a livestream of the Albany award ceremony erupted in applause. “I feel so lucky to have him as a teacher,” Parache said.

Susso returned to the school two days later, where he was mobbed by students and colleagues who were eager to offer their congratulations. “It was crazy,” Susso recalled. But the fanfare soon passed, and Susso was back to the obscurity of the everyday job he loves.

Curious about how a Teacher of the Year practices his craft, Chalkbeat visited Susso’s class on a recent morning, where he was introducing a new unit on civil rights to a social studies class of roughly two dozen 12th graders, including a few late stragglers. He was posing some big questions on race — what it is and isn’t and who gets to decide.

The topic was one, in the nation’s most segregated school system, that both he and his students had clearly given some thought. When Susso accepted his award, he noted that he taught in the poorest congressional district in the country.

Many of Susso’s students are immigrants, hailing from West Africa, the Dominican Republic, or Yemen among other countries. Having moved to the U.S. from Gambia when he was 16, the teacher has a deep affinity for the hardships and challenges many of them face. Susso’s own immigrant experience has informed his approach in the classroom.

Before leaving Gambia, Susso completed the equivalent of eighth grade and was a top student, despite suffering from a rare eye disease— a condition he hid from everyone, including his teachers and parents, and left him nearly blind.

“I shielded myself from anyone knowing,” he said, “because disability is very stigmatizing in Gambia.”

At one point, when he was 11, he traveled to a hospital, but with few medical resources, the doctors there couldn’t help. To compensate, Susso stayed up late at night to memorize textbooks, whose words he could just make out, so he could follow the next day’s lessons on his school’s blackboard, which he never could see.

Once in the U.S., he settled in Poughkeepsie, moving in with a brother’s family and enrolling in the local high school. Because of his age, he was placed in the 11th grade.

In retrospect, skipping two grades, he said, “was the best thing that could have happened to me.” Because he was so miserable, he doubts he would have graduated if he’d had to make it through all four years.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t have the ability,” something he said was also true about his students, many of whom arrive at the school reading far below grade level. “There is not an achievement gap,” he insisted. “There is an opportunity gap.”

Like some of his students, Susso often arrived in class feeling angry, hungry, or exhausted and forever out of place. “I was the only African student,” he said. “I didn’t have any friends.” Sharing a home with his brother’s family proved untenable, and within eight months, Susso was living on his own and having to support himself with after-school jobs in a country he still scarcely knew or understood.

“Based on what I went through,” he said, he tries to provide many “different opportunities for students to feel relaxed and comfortable” in his fourth-floor classroom. “That is the only way,” he said, “that learning can occur.”

His room is lined with inspirational quotes, and he likes to begin each lesson with upbeat music. That morning, Rachel Platten’s “Fight Song” was playing on Susso’s computer as two boys with basketballs under their arms and a girl in a sweatshirt began to saunter in. The girl was happily mouthing the lyrics — “Take back my life song/Prove I’m alright song” — as she pulled a notebook from her backpack and greeted additional classmates as they entered.

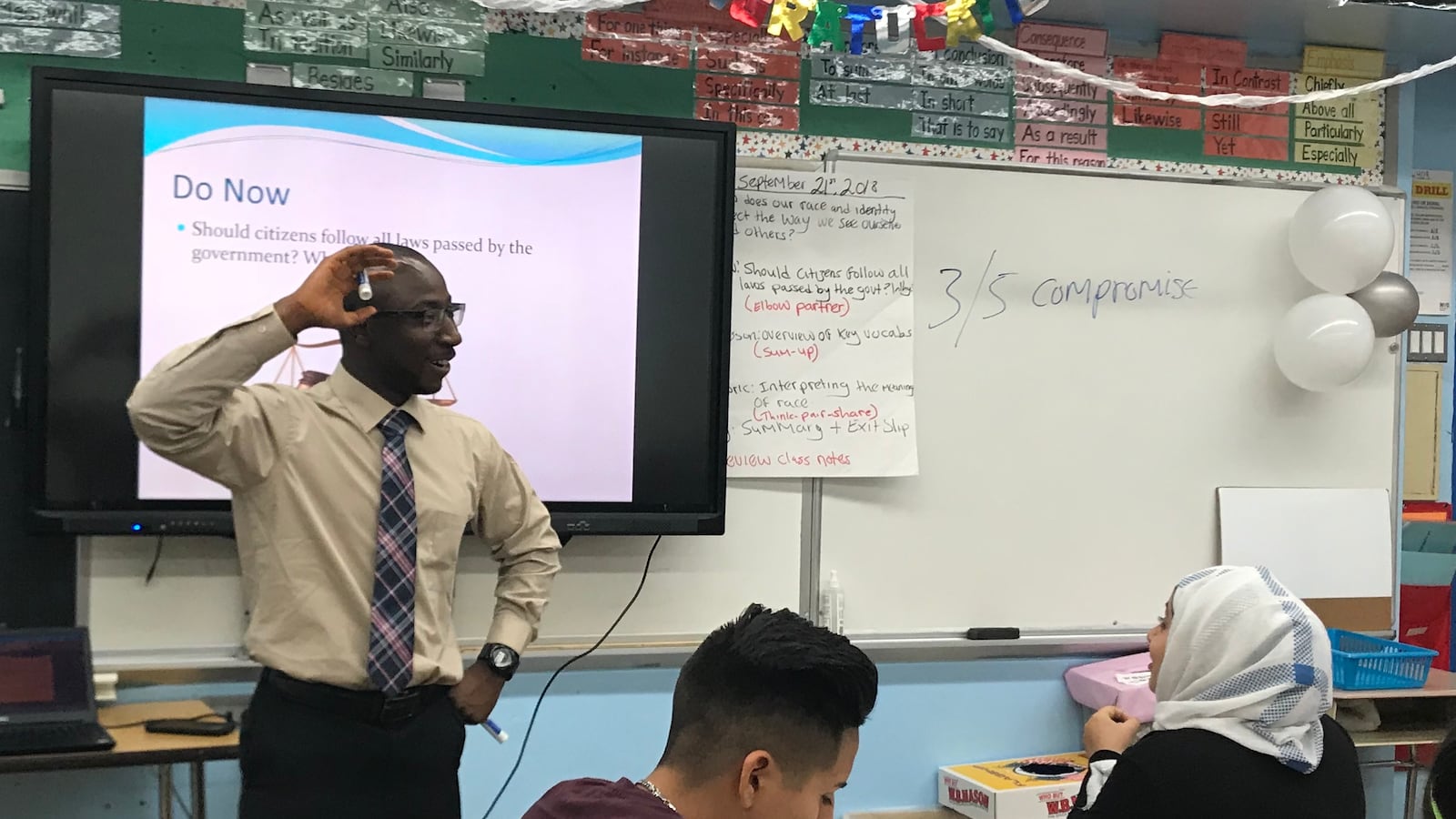

Susso then led the class in a series of affirmations — “I am somebody” and “I will leave my mark on my generation” — which were like a pledge of allegiance to the students’ future selves. Susso then had students begin a “do now” exercise, which asked for written responses to a prompt: “Should citizens follow all laws passed by the government?” He then invited students to turn to an “elbow partner” to discuss what they had written.

Up to this point, the lesson was briskly paced and well-organized but not dramatically different from other classrooms. Where Susso really shined was in the ways he got students to think hard about complex issues and the clear rapport he’d already developed with students so early in the year.

Susso believes this personal connection is critical. He’s been known to visit students’ families in the hospital and stays after class to help them learn “life skills.”

At Susso’s Poughkeepsie high school, the adults weren’t always so supportive. He recalled one incident in a math class, when a teacher asked him to solve a problem on the board. Still hiding his vision problems and unable to see the equation, Susso replied simply, “I don’t know.”

The teacher responded by mocking Susso. “We know the people who are going to drop out of college,” he recalled the teacher saying, “if they even make it there.”

Another teacher took umbrage when Susso wore traditional African garb to class.

“If people want to wear their funny clothes,” the teacher said in front of Susso’s classmates, “they can stay in their country; this is America.”

Yet Susso said he and this teacher eventually became extremely close. “He got to know me as person,” Susso said. “He saw how hard I was willing to work.” By year’s end, the teacher was having students interview immigrants around Poughkeepsie and collected their stories in a bound book for the school community to share.

Still, Susso was often carrying a heavy weight, as he knows his students frequently do as well. Back in Gambia, a beloved sister contracted Hepatitis B, and the family worked to get her a visa to travel to the U.S. for treatment. But the visa was denied. Four months later, she died.

In the years immediately after, Susso became determined to go to law school to become an immigration lawyer so he could help families avoid the fate his had endured. Many of his students now, he said, worry about their legal status and that of their families.

In college, a counselor suggested that if Susso really wanted to “empower young people,” he should become a teacher instead.

Susso followed this advice and fulfilled part of his student-teaching requirement at International Community High School in the Bronx. The principal was so impressed, she promised him a job once he got his master’s degree. At age 34, he has now been teaching at the school for more than five years.

Bespectacled and darting about the classroom in brown pants, a beige dress shirt and navy-and-pink tie, he probed his students’ views with good-natured insistence.

When he called on one student who hadn’t volunteered to speak up, she moaned, “Noooo!” And he replied with a coaxing and enthusiastic “Yessss!”

Perla Novas, who is from the Dominican Republic, said she particularly liked how Susso is funny and lets students “talk a little bit” instead of demanding silence. “He cares about us and talks about values and why we should strive to be a better person,” she said. “Not a lot of teachers do that.”

Parache, the student who had watched Susso win his award in class and who is also Dominican, argued that citizens had a special responsibility to follow “all the laws,” because, he said, “when you become a citizen, you take a vow, you make a promise, to be good.”

“So what if the government passed a law that said ‘All Dominicans are to be deported next week,’” Susso inquired. “You said we’re supposed to follow all the laws.”

A female classmate chimed up, “But it’s not just ‘all the laws,'” she objected. “We also have rights.”

“So a law can be unconstitutional?” Susso asked, before sneaking in a review of some key terms and historical concepts, such as the 14th Amendment, the three-fifths compromise (in which slaves were counted as a fraction of a human being), “myth” and “segregation,” which he asked note-taking students to define or explain.

Susso then handed out sheets that contained a historical account of a Chinese family traveling through the American South in the 1950s, beginning to tie their debate to the unit ahead. Susso asked where such a family might sit — at the front or back of a bus — given the era’s Jim Crow laws enforcing racial separation.

“The middle?” one student asked.

Susso laughed, noting there was “no middle” in those days. Some students insisted Chinese passengers would be considered “colored”; others maintained they’d pass as “white.” Susso then had students take turns reading out loud from the passage. The Chinese passengers, it turned out, had been instructed to ride with whites but felt more kinship with blacks and so insisted on sitting at the back.

One student, Nicole Mendez, noted how Susso always went “very deep into a topic” and was “very good at explaining things,” she said.

Susso again played music — this time a segment from Rihanna’s “We Found Love” — as students sought out new partners to discuss what they’d written about the 1950s story. Susso said he always provided a two-minute break about halfway through the class, just to make it more inviting. About 60 seconds later, the class was again attentive and focused.

What would happen, Susso asked, if he woke up one day on the wrong side of the bed, “and decided I am now white,” he wondered. Could he do that as the Chinese family had? Why or why not?

A discussion ensued about how Susso and students perceived race in each other and themselves — whether they were “brown,” “black,” “cinnamon,” or “pink.”

Susso asked where “the best place to see segregation” was at their high school.

One girl called out, “The lunch room!” Students nodded knowingly, as they described the self-sorting that went on. “I hang with the Dominicans,” one girl, who indicated she was mixed-race, said.

Bringing the conversation back to the American south, Susso asked who got to decide what race someone was.

“The whites determined where people sat,” one girl said, which then led to the formulation of a more general precept: “The ones with the privilege get to decide.”

Another student countered that race was just “a myth,” utilizing the vocabulary word from earlier in the lesson, and that race didn’t refer to any biological difference. But, she added, “Myths can be powerful.”

Students then summed up what they’d learned in a final individual writing assignment, their “exit ticket,” which he could review later. As the students studiously finished up, a woman’s voice blared over the loudspeaker. “Period one is now over.”

In just 45 minutes, Susso had gracefully and expertly moved his students through several different exercises: reading, writing, and deep class discussions, and provided some music and fun besides.

“He’s an immigrant like us,” Perla Novas said, as she gathered up her books to head to her next class. “He asks questions that make us think.”