When Jeanelle Valet learned that the city planned to close P.S. 92, the Bronx elementary school her three children attend, she struggled to understand why.

She knew the school had a history of low performance, but it seemed to be working for her children. And it didn’t take much research to find other schools with lower attendance rates and similar test scores that avoided a spot on the closure list.

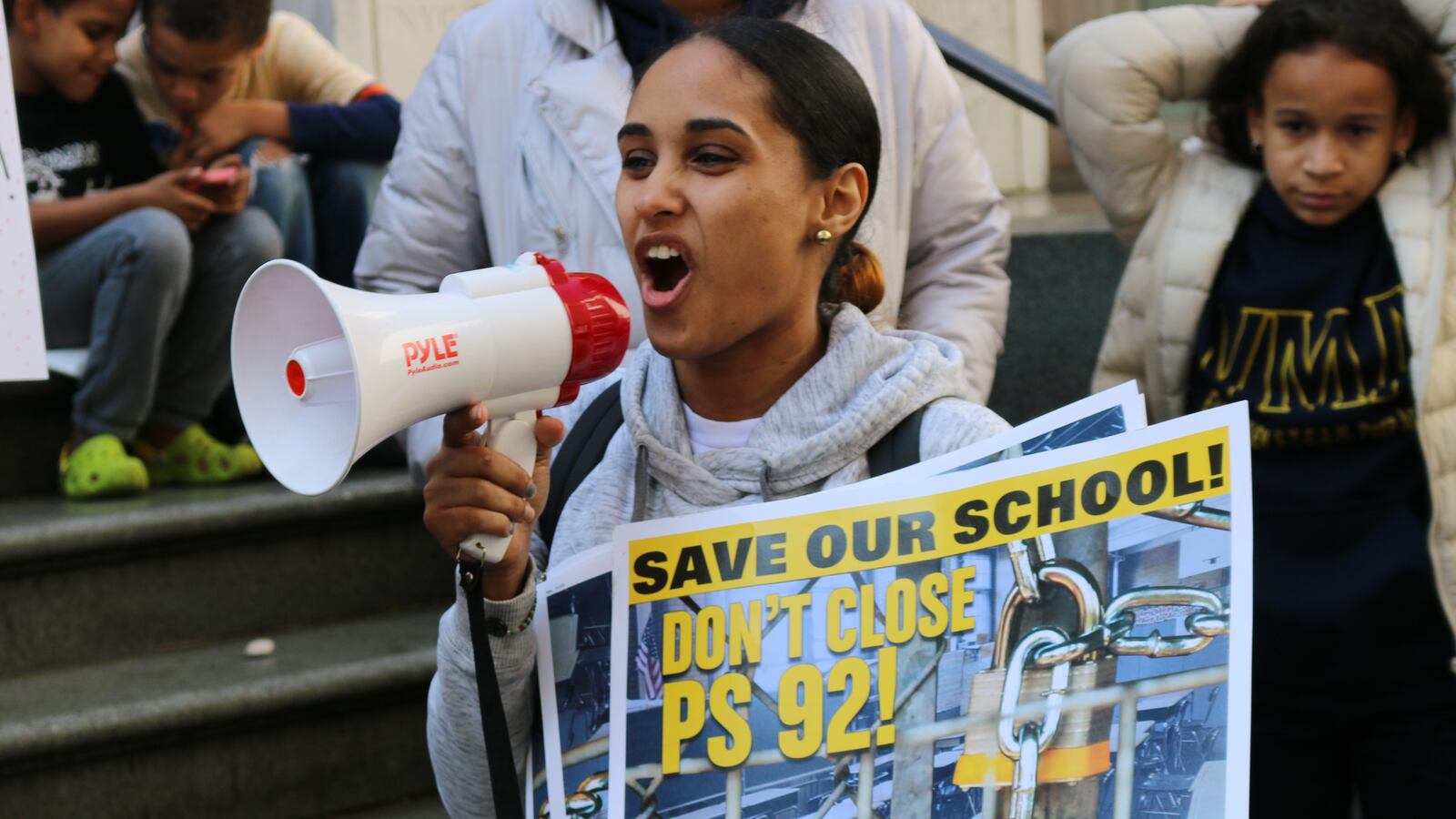

“I have gone through a lot of data for all these other schools,” Valet boomed through a megaphone as she stood on the steps of the education department’s headquarters, where advocates and parents gathered this week in protest. “There are other schools on the ‘Renewal’ list that aren’t getting closed that should be closed.”

On Wednesday, an oversight panel will vote on the city’s plans to shutter 13 schools — including P.S. 92 and seven others in the city’s “Renewal” improvement program — that officials decided are too low performing or have shed too many students to keep open. It’s the largest single round of closures since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014.

School closures are inherently disruptive and controversial — even schools with dismal academic records can inspire fierce loyalty from families and educators. The outcry against closures was loud and sustained under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who shut down dozens of low-performing schools and replaced them with new ones.

De Blasio has weathered a much smaller backlash because he has shuttered far fewer schools and on account of his $582 million Renewal program, which has flooded low-performing schools with extra social services and academic support rather than immediately closing them. Yet his approach has invited its own set of critiques.

The fact that de Blasio promised to “move heaven and earth” through his Renewal program to revamp troubled schools has prompted even some allies to question whether the program has fallen short. And the small number of closures has left parents like Valet wondering why their school was targeted when others were spared, and has fueled suspicions among some that de Blasio may be making space for more charter schools. (An education department spokesman denied that and said only four of 18 schools set to be closed or merged will be replaced by charter schools.)

Now, even as families at some of the schools rally against the closures, they are also wondering where their children will end up if the plans go through. While the city has promised to place them in higher-performing alternatives, many are skeptical — and still waiting for details.

“No one has told us anything,” Valet said.

The Panel for Educational Policy — an oversight board where the majority of members are appointed by the mayor — will vote on the closures Wednesday evening. In the past, it has signed off on nearly all of the city’s proposed closures, though five of the 13 members voted against shuttering a Bronx middle school last year. If the latest round of closures are approved, 26 of the original 94 Renewal schools will have been closed or merged with other schools.

Since launching the Renewal program in 2014, de Blasio has made clear that he would consider shutting down schools that failed to make “fast and intense” improvements after receiving extra support. Still, that has not insulated him from attacks from all sides: Critics of his approach say he should have closed the worst-off schools sooner rather than spending years trying to save them, while some ideological allies question his decision to close any schools at all.

“This administration, like its predecessor, relies too frequently on school closings as a remedy for failing schools,” Public Advocate Letitia James wrote in a recent letter to schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña. “Rather than helping students, closures disrupt whole communities.”

Even the union-backed Alliance for Quality Education — which has generally endorsed de Blasio’s turnaround strategy — implied in a statement last week that the city was partly to blame for some schools’ failure to improve, saying that the Renewal program’s support for schools has been “uneven.”

The group also argued that the education department “arbitrarily” targeted schools for closure — echoing a complaint made by many families and faculty members.

For instance, supporters of P.S./M.S. 42 in Queens have pointed out that the school has made gains on its test scores and quality reviews — even outperforming a number of other Renewal schools. Yet it is one of the schools slated for closure.

In the past, education department officials have said they consider a range of factors when deciding which schools to close.

“We look carefully at a school’s test scores, attendance, graduation rates, classroom instruction, leadership and the school’s overall trajectory for success,” education department spokesman Michael Aciman said in a statement. “For each school proposed for closure, we believe that students will be better served at a higher performing school.”

But critics say it’s often unclear how those criteria are applied to individual schools.

“There’s a lack of clarity, a randomness, in how schools are closed,” said Angelica Otero, executive director at Bronx Power, an organization that has organized parents against the closures. “That’s what feels really unfair.”

Adding to the frustration, de Blasio recently reversed his administration’s decision to close a Brooklyn high school. Because he cited community pressure, the reversal raised questions about whether politics play a role in closure decisions — while also giving other schools hope that protests might change the mayor’s mind.

“We were like, ‘Okay, it’s possible,’” Otero said when Brooklyn Collegiate was taken off the closure list. “Let’s keep working.” (Aciman, the education department spokesman, said the city reversed the planned closure after the community raised concerns about “limited high school options in Brownsville.”)

While families fight the closures, they are also worried about what will happen if they lose. City officials have promised to help students in the closing schools enroll in ones that are better performing. However, a Chalkbeat analysis found that students leaving closed schools often attend others that still perform below the city average.

Meanwhile, several parents said they are anxiously awaiting the individual enrollment help that city officials say is coming in early March after the closure plans are formally approved. For now, many parents like Magdalana Espinosa, who has children at two different Renewal schools slated for closure, do not know where their children are headed after their schools shut down.

“I’m not sure where I’m going to put my kids,” she said.