City officials have repeatedly argued that state law keeps them from changing the admissions requirements at the city’s elite specialized — and segregated — high schools.

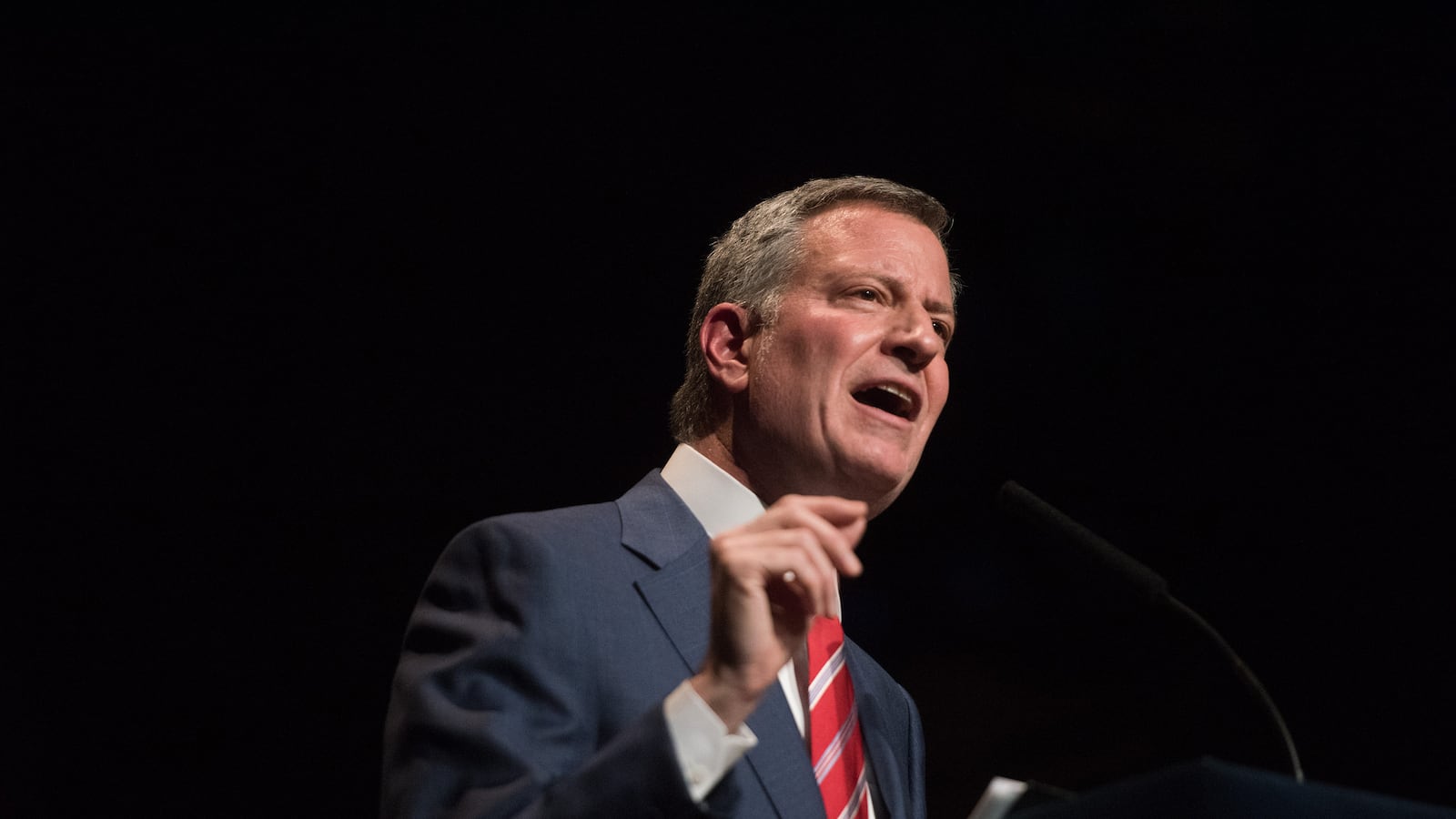

But Mayor Bill de Blasio said Friday that he will “revisit” the idea amid renewed attention to the fact that the law addresses admissions at only some of the eight schools.

“I want to have that power, unquestionably,” de Blasio said Friday on WNYC’s Brian Lehrer show, referring to changing admissions rules at specialized high schools. “I’ll revisit it because I want to find any form of action I can possibly find.”

Last week, the city revealed that only about 10 percent of admissions offers to those elite schools went to black or Hispanic students, who make up 70 percent of the city’s students. The city has launched a series of programs to boost diversity at those schools, but they have failed to make a meaningful difference.

Admission to eight of the city’s elite high schools are governed by a single test, which advocates say disadvantages low-income students and those of color. De Blasio has long been sympathetic to their argument — but has also long claimed that the city can’t redesign the enrollment process at specialized schools because they are governed by a 1971 state law.

In fact, just three specialized high schools are actually written into state law: Stuyvesant High School, Bronx High School of Science, and Brooklyn Technical High School. The city could change admissions rules at the remaining five specialized schools, experts say, with a vote from a city oversight board whose appointees are mostly controlled by the mayor.

De Blasio indicated that the city’s law department had advised him that changing the admissions rules would be difficult. But on Friday, he said: “I will talk to our lawyers again.”

“If I had my way there would not be a single test,” de Blasio added. “We are still working under a state law rubric.”

Advocates have proposed other approaches to filling the selective schools. Lazar Treschan, who has studied the city’s specialized high schools closely for the Community Service Society of New York, has recommended tweaking admissions so that the top 3 percent of students at every middle school are offered admission. Others have suggested an admissions process that weighs both test scores and geography, or a more holistic system that takes into account GPA and attendance.

It’s unclear whether de Blasio will actually take more aggressive action. Alumni groups at the original specialized high schools fiercely protected the current admissions rules, arguing that adding other admissions criteria would make the schools less rigorous.

And even if the city did successfully change the admission requirements at five of the eight specialized high schools, it would likely not have an immediate effect on overall diversity since the remaining three schools contain roughly 75 percent of specialized high school seats.

David Bloomfield, an education law professor at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center who has argued the city can unilaterally change the admissions rules, said he isn’t convinced the mayor will take action.

“It’s positive but we’ve heard this before,” he said, referring to de Blasio’s comments this morning. If the mayor believes it’s in his power, Bloomfield added, “Why doesn’t he just do it?”