Richard Carranza’s first day as New York City schools chief started with a photo opportunity: a snowy walk-and-wave into Tweed Courthouse, the education department’s Lower Manhattan headquarters, shortly before 9 a.m.

Later today, he plans to have lunch at an iconic New York City restaurant, Katz’s Delicatessen, with Mayor Bill de Blasio and his wife, Chirlane McCray. (It must be said: The third day of Passover makes an unusual choice for a visit to a Jewish deli.)

What Carranza won’t be doing: visiting any schools. This week is spring break, giving Carranza at least five work days before he’s likely to face any on-the-ground challenges. That should give him time to get to know his colleagues at Tweed and start getting up to speed on the major issues he’ll have to tackle.

The schedule makes Carranza’s first day very different from those of the most recent chancellors he succeeds. Here’s a look at what each of them did on day one.

Carmen Fariña eased into the limelight.

On her first day in 2014, Fariña made a public appearance at one school, M.S. 223 in the Bronx, where she answered questions about where she planned to take the city’s schools. As a longtime veteran of the city’s schools appointed by a mayor who had vowed to shift the education department’s direction, would she seek to roll back Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s education agenda? She said she would work, at least at first, within “the framework that existed” — though four years later it’s clear that she changed the education department substantially.

Fariña also said her first day had been busy, with lots of coffee, lunch skipped, and meeting with current staffers to talk about ways to “duplicate” their policy successes — a mission at the heart of some of the programs she created. And she also foreshadowed her hesitance to be a public figure, saying “the word chancellor kind of gives me the shivers.” De Blasio is reportedly hoping Carranza will take a different approach.

Dennis Walcott made waffles.

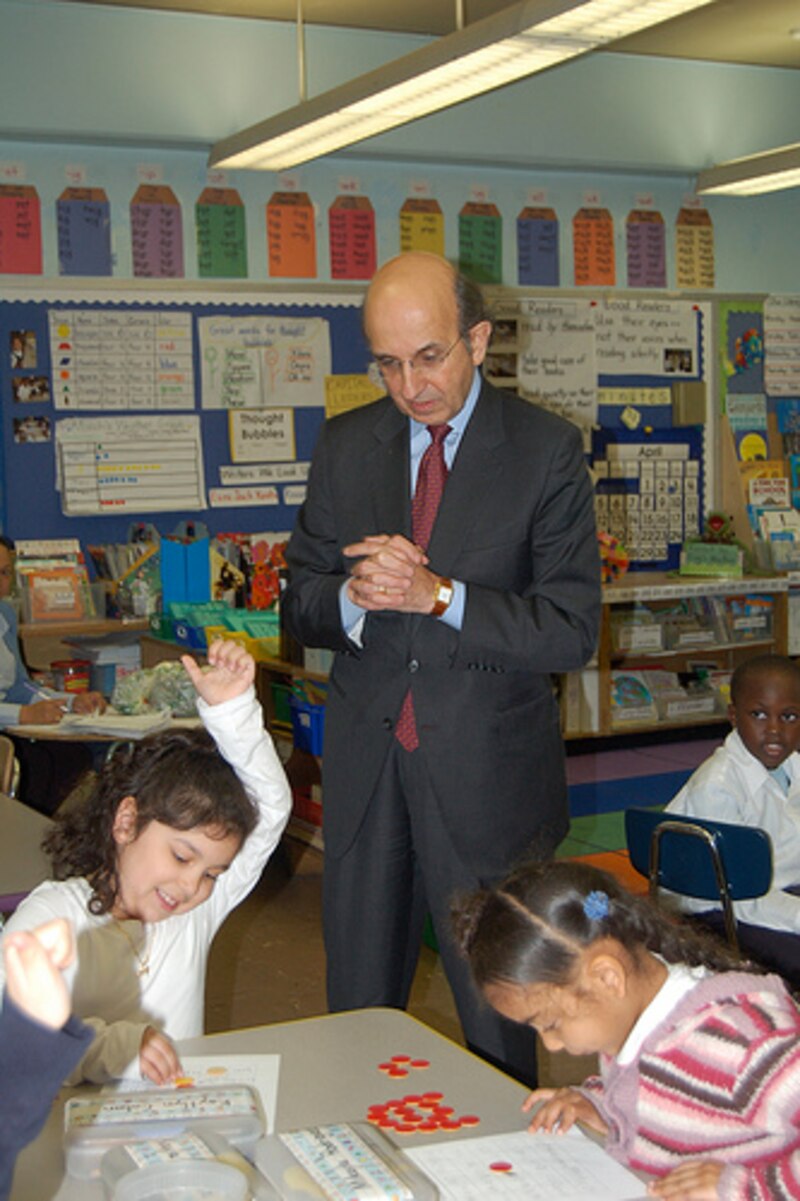

He was still a few days shy of officially taking over the city’s school system when Dennis Walcott, then still a deputy mayor for Bloomberg, stopped by P.S. 10 in Brooklyn to make his trademark waffles in an appearance that many education insiders remember as his inaugural public appearance. The visit — not even his first since being appointed — fulfilled a promise made to a third-grader to prove that Walcott’s waffle recipe (sugar-free, in keeping with his fastidious health regimen) was the best in the world. A student’s question also presaged the chancellor’s first marathon several months later. The visit kicked off a grueling — and, he said, rewarding — pace of school visits that characterized Walcott’s tenure, which lasted until Bloomberg left office at the end of 2013.

Cathie Black made what might have been her longest public appearance.

Cathie Black’s appointment came as a shock, but her first day on the job in January 2011 was thoroughly choreographed as she visited schools in each of the five boroughs. The city had time to prepare: It took several weeks between when Bloomberg picked her for state policy makers to give her the waiver she needed to run the city’s schools despite a total lack of education experience, and she didn’t take office for six weeks after that. At the time, Black told us she had visited roughly 20 schools before her official first day, when she stopped by a music-themed high school, a charter school that teaches Korean, and a school for students with severe disabilities. But her school-visit schedule quickly slowed as her public appearances became landmines for the city, and she resigned just three months after her official first day.

Oh, and Joel Klein was uncharacteristically quiet.

Schools were also closed when Klein took office in August 2002, but he didn’t stick around the education department’s headquarters, then still located in Downtown Brooklyn. “I wanted to send a clear message that I’m going to be out and in the schools,” Klein said about why he met with a deputy in Bedford-Stuyvesant on his first day. “If schools were open today, I’d be in school. Because that’s going to be a key part of my mission.”

That meeting was closed to the press, as part of a first day that the New York Times reported “represented a striking departure from tradition, and suggested that he might, at least for now, keep a lower profile than his predecessors.” (Several of them visited schools and held press conferences, according to the Times story, and one served French toast to students — likely with syrup.) Ultimately, that proved to be far from the case: Klein was a relentless leader and divisive public figure, frequently rolling out game-changing new policies during splashy press conferences without first building support from people who worked in schools.

A takeaway from Klein’s first day more than 15 years ago: A quiet first day hardly means a low-key administration — something to watch for now as Carranza digs in.