Early every school day, private charter buses rumble through the Upper West Side to ferry students from the city’s wealthiest school district into one of the poorest.

The students head to Bronx High School of Science and the High School of American Studies at Lehman College, just two of the city’s coveted specialized high schools that draw virtually no students from their surrounding neighborhoods.

Across New York City, just a handful of school districts and middle schools send an outsized share of students to specialized high schools, celebrated for their track record of preparing graduates for Ivy League colleges and high-powered careers.

The numbers are striking: Students from only 10 middle schools make up a quarter of all specialized high school admissions offers — a total of 1,274 offers, according to data provided to Chalkbeat. That’s almost four times more than all of the admissions offers to students living in the city’s 10 poorest districts combined.

That reality could be upended with a controversial proposal put forward by Mayor Bill de Blasio to overhaul admissions to specialized high schools. Rather than admit students based on the results of a single test, the city is pushing a plan to admit the top 7 percent of students from every middle school, based on a combination of their state test scores and report card grades

The proposal would require a change in state law, and lawmakers have already shelved the plan for this year. But if city officials can persuade lawmakers to approve the change, it would cut off a reliable pipeline into the city’s most elite high schools — a tiny subset of selective middle schools — and draw more top performers from every corner of the five boroughs.

“ZIP code is limiting destiny right now in New York City,” de Blasio said at a recent press conference.

Critics, though, say the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test helps preserve the high standards at the schools, considered by many to be the crown jewels of the system. They suggest other ways for diversifying the schools, such as making test preparation more widespread.

Chalkbeat compared education department data of specialized high school offers in schools and districts across the city. Here are some highlights from the numbers.

Some districts send many students to specialized high schools, while others send almost none.

Affluent District 2 — which stretches across Lower Manhattan, most of Chinatown and the Upper East Side — accounts for almost 13 percent of all specialized high school admission offers. That number is even more eye-popping when you consider that it enrolls only about 4 percent of all the city’s public school eighth graders.

Click on the map to learn which districts send the most students to specialized high schools.

The 10 districts that are home to the most black and Hispanic students made up about 4 percent of admissions offers.

Just because a student was offered admission, that doesn’t mean that he or she will ultimately choose to go to a specialized high school. In fact, research has shown that black and Hispanic students, and girls, are less likely to accept their offers, compared with Asian students.

The district figures include admissions offers that were made to students in private schools and those who were homeschooled. Private school students earned about 13 percent of offers.

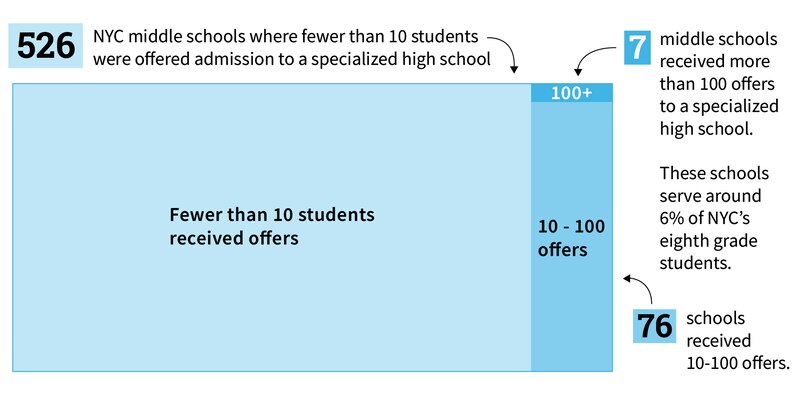

A tiny number of schools send a disproportionate number of students to specialized high schools

The disparities are so large that just two middle schools — The Christa McAuliffe School and Mark Twain I.S. 239 — get more students into specialized high schools than the city’s 10 poorest districts combined. (One caveat about these numbers: The district offers are based on where students live, not where they attended school. So it’s possible that students living in the poorest districts are enrolled at Mark Twain, which is open to all students regardless of where they live in the city.)

“If you think it’s unlikely that only a couple of dozen schools have a monopoly on talent, then we have a problem,” said Richard Buery, a former deputy mayor for the city who has endorsed de Blasio’s proposal to change specialized high school admissions.

All together, the top 10 middle schools enroll only about 18 percent black and Hispanic students. They are among the most sought-after in the city, but they are also extremely selective.

Many top-sending middle schools select their students based on test scores, their own exams, interviews, attendance, and other factors.

The numbers get at an ongoing debate over whether schools should be allowed to “screen” students in this way: While some say high-performers are better served in classrooms where most students are like them, others say that separating students by ability exacerbates segregation because black and Hispanic students are more likely to struggle in school.

Among the middle schools sending the most students to specialized high schools is Booker T. Washington in District 3, which is at the center of another contentious integration battle. The superintendent there has proposed setting aside a quarter of seats at every district middle school for students who are low-performing.

The plan has sparked an uproar from parents who worry their high-achieving kids will be shut out of the most sought-after middle schools. The city’s numbers sheds light on the backlash: More than 53 percent of Booker T. Washington eighth graders are offered a spot at specialized high schools.

Kristen Berger, a parent on the local Community Education Council who has pushed to integrate the district’s middle schools, said the current system fuels competition for the few schools that feed students into top-tier high schools.

“I think it’s part of a wider New York angst,” she said. “We’re looking downstream like, ‘What elementary school goes to what middle school, goes to which high school, goes to which college?'”

She also said that it calls into question the city’s high school choice process, which is supposed to allow students to aim for any school, regardless of where they may live.

“We certainly wouldn’t want middle schools to be a limiting factor,” she said. “We would want all students to have the full range of options, whether it’s for middle school or for high school.”