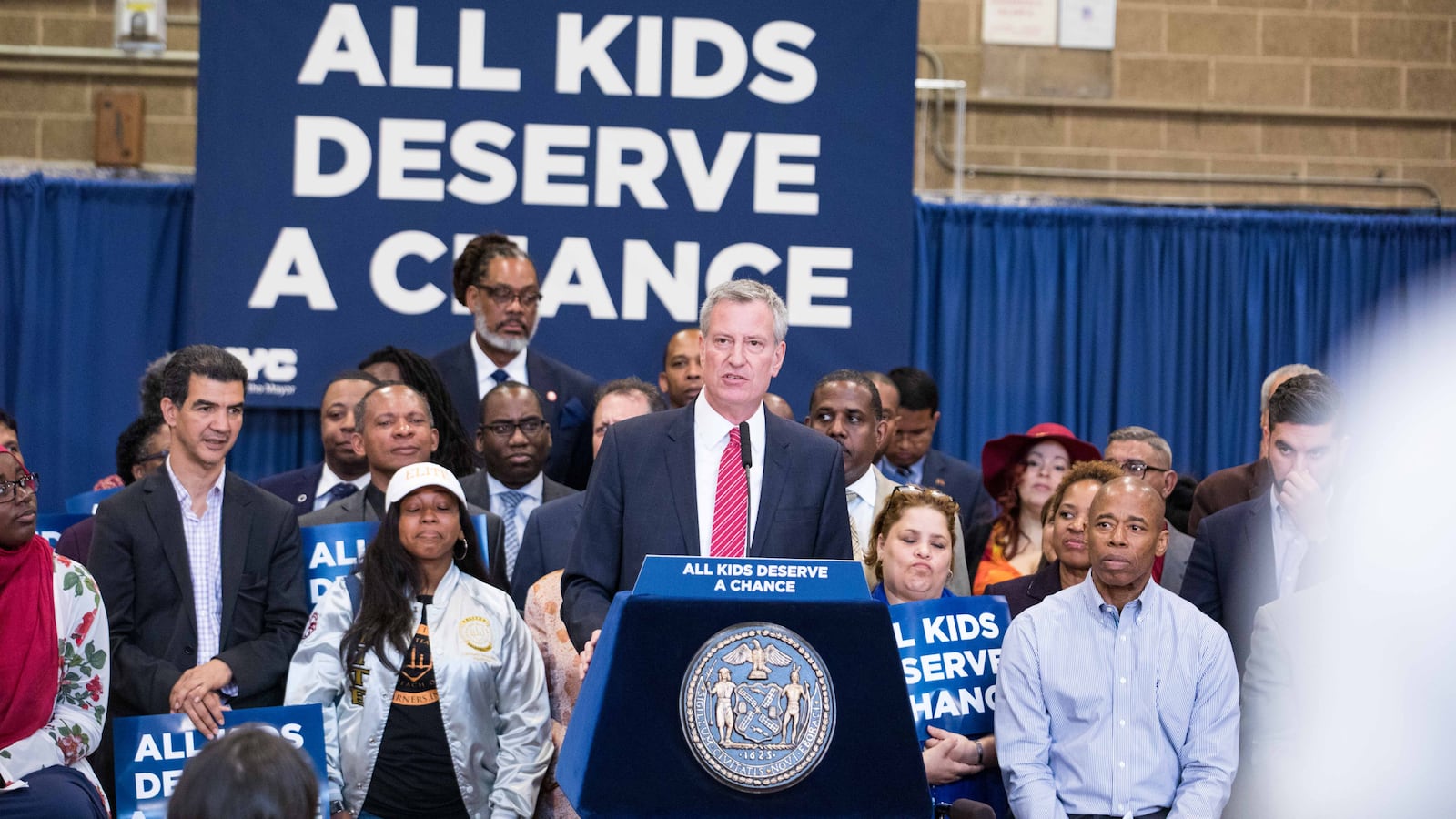

When Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a plan to scrap the exam that serves as the sole entrance criteria for New York City’s vaunted specialized high schools, he led supporters gathered in the gymnasium of a Brooklyn middle school in chants of “The test has to go!”

Just days later, protesters flooded the steps of City Hall to defend the Specialized High School Admissions Test. “What do we want? SHSAT!” they yelled.

The pushback against de Blasio’s plan hasn’t stopped. In the more than two months since he launched a push to overhaul admissions in an effort to admit more black and Hispanic students, former allies have backed away, political opponents have put forth their own proposals, and the mayor has contended with a steady stream of protests.

The debate gets emotional quickly, and facts can be hard to find. Here’s our guide to the arguments against de Blasio’s plan and the most common alternatives proposed: what’s true, what might work, and what probably won’t.

Argument: The SHSAT shouldn’t be eliminated because it will cause the quality of students’ education at the specialized high schools to suffer.

This argument hinges on the idea that the students admitted under de Blasio’s plan will be less prepared academically. To judge it, we need to know how the academic profile of students admitted to specialized high schools would change. The city has some answers: Under de Blasio’s proposal, which would offer admission to top middle school students across the city, the projected average grade point average and state test scores of the incoming classes would remain about the same as they are now.

The education department says that students’ state test scores would slip slightly: incoming students would go from an average level 4.1 to a 3.9 (out of a possible 4.5). The grade point average of admitted students would hold steady at 94.

Then, there’s the question of whether those are appropriate metrics for judging who is prepared for the specialized schools. Research suggests that GPA may be a better predictor than the SHSAT of how students will perform in specialized high schools, at least for those who are admitted with lower scores on the entrance exam. But some argue that the specific kind of rigorous preparation typically required to succeed at the SHSAT helps students do well at the demanding schools, too.

Integration advocates have pushed back against this argument because it suggests that black and Hispanic students aren’t as bright as the students who now fill specialized high schools.

Argument: The SHSAT shouldn’t be eliminated because it is a fair and unbiased way to select students.

Defenders of the SHSAT say it is an objective way to determine merit: If you do well enough on the test, you’re in.

The exam is particularly appealing to Asian parents, who have said they worry that more subjective measures, such as interviews, would be biased against their children. Case in point: the recent controversy at Harvard, where Asian students vying for admission were consistently assigned lower scores on personality traits, according to legal documents in a suit claiming the university discriminates against Asian applicants.

A recently released study also found the SHSAT generally predicts which students are likely to be successful early in high school.

There’s no doubt that the exam is a clean-cut way of making admissions decisions — and clarity is rare in the New York City high school admissions system, where sought-after schools can all have different criteria and students are eventually admitted by an algorithm.

But we also know that not all eligible New York City students are taking the SHSAT, and its use shuts out lots of students who can’t afford test prep. Students also have to know how and when to sign up to take it. (The city has tried to address some of those issues. It hasn’t worked.)

Researchers say the recently released study doesn’t do much to settle the debate around the SHSAT, either. “It tells us something we already knew: Kids who do well on the SHSAT do well in high school,” Aaron Pallas, a researcher at Columbia who reviewed the study, recently told Chalkbeat. “But it doesn’t tell us what is the best combination of factors that predict who might do well in an exam school.”

Argument: The SHSAT shouldn’t be eliminated because the proposal is trying to solve a problem that doesn’t exist — a lack of diversity.

The debate around specialized high schools is complicated by the fact that they are already full of students of color: enrollment is about 62 percent Asian.

Some argue that changing the admissions system to admit more black and Hispanic students would come at the expense of Asian students, who have the highest poverty rate of all racial and ethnic groups in specialized high schools (but not citywide). At the eight schools that use the SHSAT for admissions, 63 percent of Asian students come from low-income families, according to data provided by the city.

“What’s so frustrating about the mayor and City Hall’s narrative is that it seems to, at best, deny that Asian Americans are people of color too,” Ron Kim, a state assemblyman who represents heavily Asian neighborhoods in Queens, recently told Chalkbeat.

But the disparity between the specialized schools and the city is wide. Only 10 percent of students at the high schools are black or Hispanic, even though those students make up 70 percent of public school enrollment citywide.

Specialized high schools fall short on a range of other diversity measures, too.

Citywide, about 74 percent of students come from poor families. About half of all students in specialized high schools come from low-income families. At High School of American Studies at Lehman College, a small specialized high school in the Bronx, the poverty rate is only 20 percent.

The specialized high schools also enroll a tiny number of students with disabilities, and almost no students who are learning English as a new language.

Research has shown that integrated classrooms can benefit all students. Studies have found that racially and ethnically diverse classrooms can reduce prejudice, improve critical thinking, and lead to high levels of civic engagement.

“Learning doesn’t just involve balancing multiple extracurriculars, enrollment in several Advanced Placement classes and acceptances at Ivy League institutions,” Bo Young Lee, an Asian-American graduate of Stuyvesant recently wrote in an op-ed for the New York Daily News. “It’s also having a perspective challenged and broadened by others who look and live differently.”

Argument: Admissions to the high schools shouldn’t change because they’re already producing successful students, many of whom come from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Students of color and those who come from poor families often lack access to schools with experienced teachers, advanced courses, and strong graduation records. Specialized high schools offer all that, plus a reputation for sending graduates to top colleges.

But research suggests that the stellar results of specialized high schools have more to do with the students themselves.

Susan Dynarski, a professor at the University of Michigan, recently reviewed two studies on specialized high schools in both New York City and Boston that were conducted by other academics. She summed up their question like this: “Do the exam schools produce academically outstanding graduates, or do they simply admit stellar students and enjoy credit for their successes?”

Two studies suggest the latter, at least for students who were admitted to specialized high schools with lower SHSAT scores. They found that specialized high schools had little effect on whether those graduates went on to college, were admitted to a selective university, and whether they earned a post-secondary degree. (There could be other benefits, outside of academic measures or later in life, of attending the selective schools.)

“While the exam school students in our samples typically have good outcomes, most of these students would likely have done well without the benefit of an exam school education,” researchers wrote in a 2014 report on Boston and New York.

One counterproposal: Increase access to the test — and to test prep.

Rather than scrapping the SHSAT, many have called on the city to expand test prep to level the playing field. Others argue that prep courses should be more widely available — and better advertised — so more students have a chance to actually take them.

The city has already tried to tackle those issues, and it hasn’t made a dent in changing the demographics at specialized high schools.

The city has begun to offer the SHSAT on a school day at some middle schools in underrepresented communities, and boosted public test prep programs and outreach to increase the number of test-takers. Those efforts haven’t resulted in many more black and Hispanic students passing the exam.

Another counterproposal: Focus on improving elementary and middle schools first.

Some SHSAT defenders say the key to helping more students do well on the exam is to make sure they get a solid education earlier in their schooling. Rather than scrapping the test, the city should do more to make sure students can reach that bar — and that means investing in schools that have long been under-resourced.

“The results of the SHSAT are merely a reflection of the failure of the city to properly educate our black and Hispanic students,” Tahseen Chowdhury, who attended Stuyvesant, recently wrote in an op-ed.

Integration advocates call this argument a red herring since it suggests that unless everything can be solved at once, nothing should change. It also suggests there aren’t more black and Hispanic students already in the system who are capable of doing well in specialized high schools.

The reasons why schools struggle are complex, and often tied up in issues relating to segregation and poverty. Educators and policy makers far beyond New York City have grappled with how to improve academic outcomes for the country’s most vulnerable children, but there has been slow improvement in test scores and graduation rates for black and Hispanic students.

Meanwhile, the existence of New York’s robust test-preparation industry reflects the reality that many families turn to outside help — regardless of the quality of their child’s school — to prepare them to win a spot in specialized high schools.

A third counterproposal: The city should expand gifted and talented programs so more students are ready for advanced academic work.

Many alumni and elected officials have called on the city to expand gifted programs, which are seen as a reliable pipeline into specialized high schools. At the Anderson School in Manhattan, which has one of the most selective gifted programs in the city for elementary school, 76 percent of eighth-graders who took the SHSAT got an offer to a specialized high school this year.

“If we do that, we would not have a diversity problem,” Wai Wah Chin, president of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance, said at a recent rally at City Hall. “We need to meet the needs of children who are above grade level.”

But only 22 percent of students in city gifted programs are black or Hispanic. Absent specific integration measures, experts say that an expansion of gifted programs probably won’t help more of those students get in. The city has already expanded a new kind of gifted program in a few neighborhoods, resulting in more diverse classrooms.

Still, just like specialized high schools, admission to gifted programs usually hinges on the results of a test. Few children take the exam in poor neighborhoods, where schools often enroll more black and Hispanic students. An even smaller number score well enough to get into a program, which many experts attribute to extensive test prep.

“As long as gifted and talented program admissions are based on a single test, advantaged families will be able to game the system by prepping for it,” researchers Allison Roda and Halley Potter, who have both studied gifted programs in New York City, recently wrote in an op-ed.

There’s also the unanswered question of whether gifted programs serve as a funnel to specialized high schools simply because they admit students who do well on tests and come from savvy families — or because of the impact of the schools themselves.