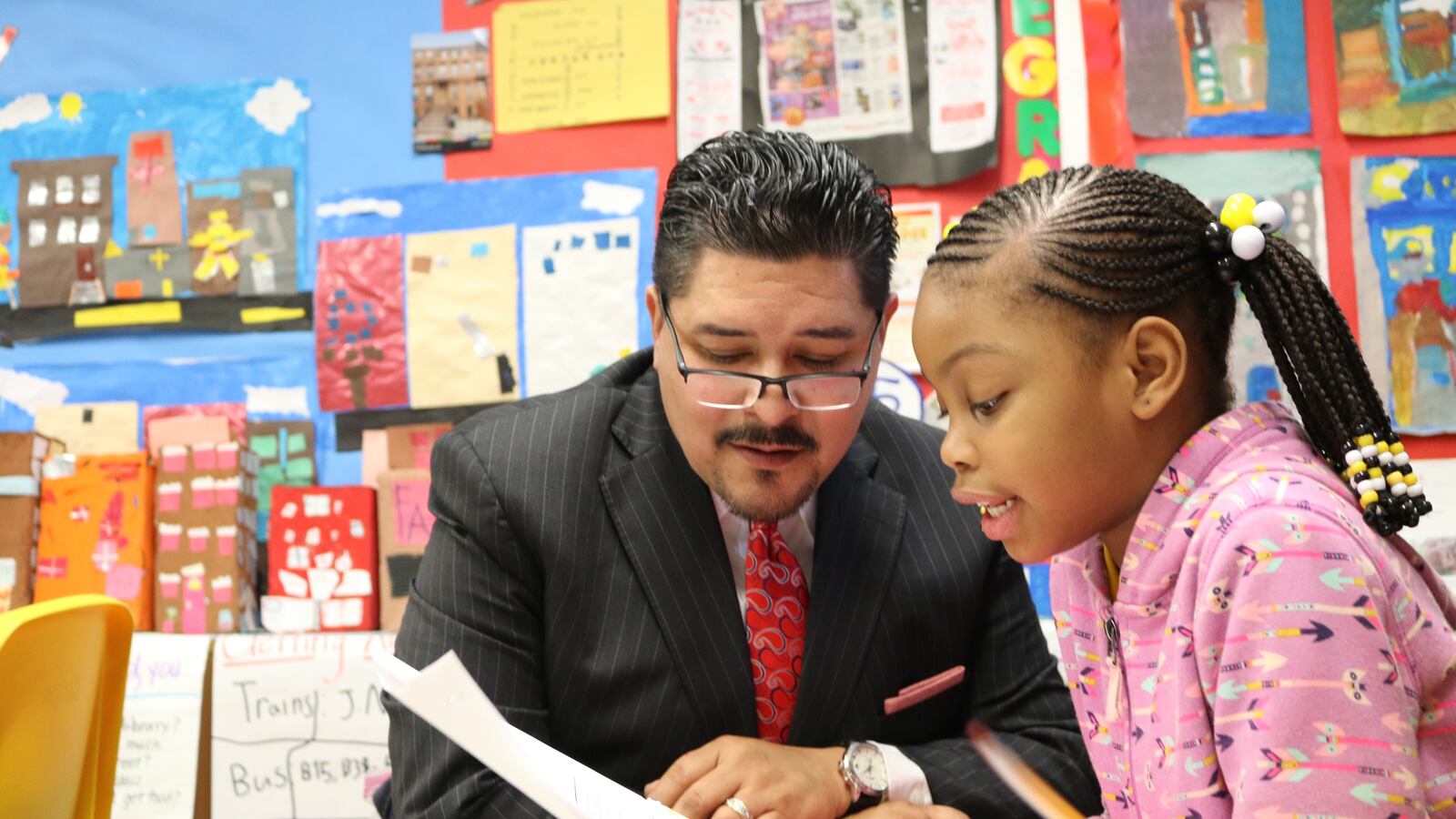

Richard Carranza jokes that his colleagues must be tired of hearing him ask the same questions.

Four months into his role as New York City’s schools chief, Carranza has had a chance to get under the hood of the country’s largest school system. And for each policy the city pursues, Carranza wants to know: “What’s our return on investment? How do we know? How do we prove it?”

His attention to hard numbers is just one of the ways that Carranza’s tenure promises to be different from that of his predecessor, who favored stories over statistics. He has charted his own course in other ways, by tackling school segregation head-on, and shaking up the leadership structure for how schools are supported. (Still, he’s not going at it totally alone: Carranza said he grabs coffee periodically with former chancellor Carmen Fariña, whom he called a “great lady.”)

Carranza’s new approach will get tested this September when more than a million students head back to school — ushering in his first full school year as chancellor.

In an exclusive interview with Chalkbeat, Carranza made it clear that he enters the year with more big questions on his mind, like whether New York City’s approach to gifted admissions is fair. He’s also finding some things he likes about the current system — toning down some of his early criticism of the city’s controversial Renewal school turnaround program. And he’s already thinking about what he wants his legacy to be in New York City.

Here are highlights from our Friday interview, condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

How have you been spending your summer? What have been your priorities and who have you been meeting with?

This summer has been super busy. I spent a lot of time, obviously, with the reorganization. (Carranza pared down his executive staff and added new roles, including executive superintendents and a Chief Academic Officer. Read more here.) I’ve been interviewing and hiring people. We’ve been also doing some reconfiguration with how the Department of Education is organized so that we’re better able to function on delivering what we’ve promised. I’ve been spending a lot of time still — it’s a big city — meeting people.

I’ve been spending a lot of time in professional development with principals and teachers and central office people. One of the things I really try to do is not just drive by, “Hey everybody. It’s nice being here.” And then I’m out. I try to actually spend time, and preferably at least half a day — which is really hard to do, and sometimes I can only spend an hour or two. I really want to get a flavor: What is it that we’re doing in terms of professional development?

What I’ve also been doing is, as I learn more and more and more about the DOE and what the initiatives have been over the last four of five years, trying to understand where we are with them. I think people are kind of sick of me around Tweed, because I keep asking, ‘So what’s the return on investment? How do we know? How can we prove it?’

One of the things that I’ve heard a lot of comment about from folks in the department and school-based folks has been the weight of bureaucracy on the day-to-day work. By that I mean the paperwork that people have to do or the processes to get stuff done that may not make sense. One of the directives I’ve given to the folks is “weeding the garden.” We need to weed the garden of stuff that’s just a time suck or it’s not helpful to the work that we do.

What specifically do you think should happen at schools that are low performing? When you took the job, you meet with people around the city and produced a report where you talked about schools needing more support. But what should happen after schools have received support and improvement isn’t clear?

I believe that when you look at improving schools or empowering schools to improve, one of the things that you can’t do is just looking at that on a short-term basis. By that I mean: You can name the schools, you can put them in a group of schools, you can invest resources, and then once they get better, you take away the resources. Well guess what? They’re going to go right back.

A much better approach is to really look at the conditions. Do a root cause analysis. What are the challenges that schools face — and not just the school, but the community? You also have to do a systems scan, and by that I mean: Are there policies, are there decisions that are made that are not inside their control? For example, have we changed a boundary line? Have we implemented a screen somewhere? Have we implemented a specialized program somewhere that impacts, negatively, this school that we’re looking at? Then the third thing you have to do is then align resources based on that needs assessment — not for a certain amount of time but as a way of doing business.

We’re in the process of doing that analysis right now with all of our schools. Obviously, schools that had previously been named as Renewal schools and even the schools that have moved into a Rise status, they’re part of that list. But there are other schools as well.

But after you’ve done those levels of analysis and you feel like schools have been given adequate time, is there an end point? Do you believe in school closures at all, after all those things have been tried?

I think we have to be able to serve students. I don’t talk about school closures because when you start talking about, “The end is going to be the ax,” then that’s never been very motivating for anybody. What I talk about is what we’re going to do in advance, and the process. But I guarantee you in every school I’ve ever worked with, when you’re really clear about that needs assessment, you’re really clear about the current condition, you’re really clear about where you want to get, the process itself will make it very clear: If we’re not able to do this, then we have to do something different for the students we serve.

But I really don’t talk about school closures because that’s really not a goal.

But even if it’s not a goal, is it a policy tool that could be used?

Let me be clear: I’m not scared of closing a school if it’s not serving the needs of the student. My experience, nine times out of 10, has been that we haven’t done all we can do, to actually give schools that are struggling to improve, the right conditions, the right resources, and the right support to actually improve.

When we first sat down, one of your initial critiques of the Renewal program was that there hadn’t been a clear “theory of action” and that “makes it difficult” to talk about what outcomes to expect. You said you were working on this “very, very quickly.” So what is theory of action now, and what are the outcomes we should be looking for?

When we met, I hadn’t yet had a deep dive with the person who had taken over Renewal, Cheryl Watson Harris. I was extremely impressed by her strategic way of looking at the work. It coincided almost perfectly with the way I look at the work. You have to have great leadership. You have to empower. And you have to train teachers for the students you have. You have to have a strong curriculum. You have to have systems and structures in schools that replicate good practices. You have to have a social-emotional community schools approach, and you have to empower communities and parents. That’s why she’s now the senior deputy chancellor, in charge of all of the supervision of all of our schools.

So my theory of action is: If we take the time to do a root cause analysis, and understand all of the facets involved with a challenging school, if we align resources to meet those root cause issues, if you have the right people in place and if you are persistent over time, you will be able to turn around a school and make it a good academic learning environment.

Renewal was supposed to be a three-year program that’s now going into year four. What’s the plan after this year? Are there any changes in the works?

We’ve learned lessons from the Renewal implementation over the first three years. As you know, we’re about to announce nine executive superintendents, which will have a very strong academic leadership role in the geographically based field service centers in the city. Those executive superintendents will take on much more responsibility for those previously called Renewal schools And those nine executive superintendents will be networked, working as a group, around supporting the schools that are in their areas.

You had three and sometimes three or more people giving direction to Renewal schools. It was a little chaotic.

Now you’re going to have a very clear line of accountability. You’re going to have an executive superintendent working with the superintendent, supported horizontally by our school improvement strategies and teams. We’re going to have a much more coordinated way of not only doing the needs assessment that I talked about, but also making sure that we’re providing the appropriate supports and then holding ourselves accountable for what we say we’re going to do.

When you say “previously labeled Renewal schools,” do you imagine these schools will shed that label, and under this new structure, they will just be schools that get targeted support through that? Or is that a decision that’s not been made yet?

I don’t refer to them as Renewal schools, only because — not that that program has gone away, not that that focus has gone away — I just look at the work of improving schools in a little bit of a different lens. I call them “schools of opportunity,” because this is our opportunity to do some very specific, strategic work within schools.

What problems are the reorganization solving?

Part of my analysis, which was then confirmed when I did my listen and learn tour, was that it was confusing where accountability lied in the organization. So as principals worked to meet the needs of their schools, they often found it confusing as to who they went to, to get support.

In addition, it was very difficult for us to actually coordinate with agencies in the city or community-based organizations wanting to do work on a number of different issues like homelessness or foster care kids, because components of what we did to support those kinds of students were in various departments across the DOE. It was very hard to build a strategic way of doing the work. What the organizational shift did was solve for a lot of those issues. Like strands of work are now in like structures, led by someone who has a very clear line of accountability.

In the case of our academic program, what I found was that you had some really hard working people in Teaching and Learning doing a lot of great work around curriculum, coaching, leadership development, you name it. I had great, hard-working people working on issues relating to English Language Learners. Great, hard-working people in special education. But rarely did they work across each other’s silo to actually have an integrated way of doing the work. That’s why I created the Chief Academic Officer position. The Chief Academic Officer will be responsible for those three strands of district work.

I think a cabinet of 22 people, which is what I inherited — great people — it’s unwieldy. So the cabinet is shrunk to nine. My cabinet touch every aspect of everything that happens in the district. It’s my way of being able to not only collaborate but to give direction, hold accountable, and also be clear about implementation of initiatives that we have in the district.

Final thing I’m going to say: One of the biggest complaints that I heard from parents was, who do I go to? I have a problem in my school — who do I go to? And that’s why they ended up emailing me. So with the executive superintendents, there’s an executive superintendent for Staten Island who has the authority to make decisions for what happens on Staten Island, who has the responsibility for addressing and working with parents and community members on Staten Island, who is going to be intimately knowledgeable about what happens on Staten Island. In other words, it’s bringing the decision-making and accountability closer to the ground.

Heading in a different direction: What did you make of your visit to a Success Academy school? Eva Moskowitz, who runs that network, said that you seemed more friendly to charter schools. Is that an intentional shift?

I like to think I’m a collaborative guy. I think I’ve met pretty much all of the charter school leaders in New York City by now. My approach is always to talk about the work from the perspective of, “What’s good for kids and what’s the educational value in us working together?” I don’t go into those meetings assuming that I’m going to have an adverse reaction or an adverse relationship with anybody in the meeting. I never do that any way.

I’ve also made the effort to actually go into charters — Success Academy being one of them.

I will continue to look to find places where we can actually do collaborative work together if it’s going to help kids in New York City.

We want to talk about specialized high schools. You and the mayor have proposed a plan to admit more black and Hispanic students at the schools by eliminating the test that serves as the sole admissions factor. But the rest of the school system is also segregated, and many of our readers have asked whether you plan on taking an active role in desegregation efforts beyond specialized high schools.

Let’s go over the record. Within months of getting here, the mayor and I have now proposed a plan. Is it a perfect plan? Some people say yes, some people say no. But we’ve proposed a plan that’s never been proposed before around, ‘How are we going to create more opportunities for students in specialized schools?’

I think it’s also important to understand that when you talk about diversifying schools, you obviously are talking about not only diversifying the students who go to the schools, but then from the school improvement perspective, being really clear about what are the components that we want to make sure are working well in every school. As we work to improve schools that have historically not done well, you’re going to see more and more opportunity for students. But you can’t do that with just talking about integration. You also have to talk about curriculum. You have to talk about instruction. You have to talk about leadership. You have to talk about resource allocation.

And then you have to talk about systems and structures that advantage some schools and disadvantage other schools. That’s where the hard rub is because people will always equate that to a zero-sum game. I don’t think that anyone can deny that there are structures in our system that advantage some schools and disadvantage other schools, I’m asking the question: Is that ok? I think it’s a worthy conversation to have.

What personal role did you play in pushing for admissions changes at the specialized high schools?

The mayor and I, when we spoke about my coming to New York City, knew what he was getting. He knew how I grew up, where I grew up, what my educational pathway way was, what my leadership pathway has been.

So all I can say is that, in all of the conversations I’ve had with the mayor prior to my arrival and since my arrival, I can tell you the mayor is passionate about making sure that our schools are just as diverse as our city. He’s passionate about making sure that students, in the communities where they live, have great options for going to school. He has never bridled me and he has never told me not to talk about this, and he’s never told me what to talk about.

But he and I have had, like two grown men, lots of great conversations about this.

Was it already on the table when you came in, or was it something that developed after you got here?

I did my homework when I was going to come to New York City. So I had a working knowledge of what the big issues were, and given my background, we talked about it.

One of the things that I appreciate is, what the mayor hired was an educator to be the chancellor and he lets me do my job.

The proposal has been met with backlash, particularly from parents in the Asian community. Do you wish you would have done anything differently in the roll-out to announce the admissions changes?

There always is an opportunity for more input and buy in. But I think subsequent to the roll-out, where some aspects of the community have balkanized and sort of taken a stance, that wouldn’t have been any different had we done more robust engagement process up front. Since that roll-out, though — and nobody really writes about it, and that’s good — but I’ve been meeting with folks. I’ve been starting to have some really substantive conversations.

We have a very similar model for admitting students to gifted, and a similarly segregated population. Is that acceptable, and what do you think education should look like? Should we have it at all?

We probably should be really clear about what we mean about truly gifted. The student that is doing algebra in the third grade, that’s a gifted kid. But are we really talking about that when we talk about gifted and talented programs? I don’t know. I think sometimes it’s ironic where folks will say, “Oh, if you’re going to identify a student for gifted and talented it shouldn’t be just one test.” Kids are kids. It should also be teacher observation. It should be all these other multiple measures, which I think is a good idea. But then it comes to specialized high school admissions and we all say, ‘Oh, no. No, no. It’s just one test.’

But that’s largely not how it works in gifted right now. Largely, it’s just one test.

And I think that’s not a good idea. here is no body of knowledge that I know of that has pointed to the fact that you can give a test to a 4-year-old or a 5-year-old and determine if they’re gifted. Those tests — and it’s pretty clear — are more a measure of the privilege of a child’s home than true giftedness. We should really have those conversations — including, “What is gifted and talented?” If you’re going to assess for gifted and talented, how do you do that? When do you do that? And what makes sense?

When you look at the disparities in representation across this system, you have to ask the question, do we have the right way of assessing and making decisions about students?

The mayor wants to make sure every second grader is reading on grade level and has placed literacy coaches in high needs schools to help reach that goal. Some recent research shows the program hasn’t had a positive effect, but the city is adding more coaches. What will be different this year?

When it comes to universal literacy, keep in mind that it’s pretty nascent in its implementation. We’ve changed the assessments we’re going to be using because I wasn’t satisfied in the assessments we were going to be using. It didn’t give us an ability really to compare across the system or even to other systems. I can tell you that the professional development that our coaches are going to be providing to teachers and the coaching is going to be much tighter and much more aligned. For example, if you’re doing a balanced literacy approach, and kids come around a kidney table with a teacher, there are certain protocols you should follow and certain information you should be gathering that helps you then makes the decision about what the next instructional practice is. As I looked at some of the evidence, it wasn’t always clear to me that we were really clear about what that looked like.

When you’re done here, in maybe three years, how are you going to measure your own success? What do you hope to have accomplished, especially within the specific issue of segregation?

My goal is that I’m not going to be done here for another 20 years — that the results are going to be so good in three-and-a-half years that whoever is the new mayor is going to say, “Why are we going to change this?” That’s my goal. But I will tell you that whenever we’re done here, I’m going to be able to look back in three very general areas where I would like to have liked to have seen us really move the needle.

First and foremost is around curriculum and instruction — that we will have a curriculum that is tight. It’s going to be inclusive of all students — all ethnicities, all gender identification types, LGBTQ, everybody is seen in their curriculum. That we’re going to have great implementation, that we’re going to have great professional development for teachers that’s embedded. And we’re also going to have great supports around teaching in a very restorative way so that we have good systems and structures around that.

The second one is going to be around equity, that we will have moved the equity agenda in New York City so that we’re actually leading the nation. It gives me chills in a bad way every time I hear somebody reference the fact that we’re the most segregated school system in America. So I would hope to say that in the equity front, that we’ve actually dealt with our issues.

And then the third area I think is really, really important as I look back is that I want to make sure that we’ve done the work to empower parents and communities where they are. I’m not convinced, despite our best efforts, that we’ve actually met communities where they are. And we’ve not done that in people’s native languages.

Is there anything we didn’t ask you about that you want us to know?

I was at a meeting this morning and then when I got done with the meeting I walked into a coffee shop. I bought a cup of coffee and as I was standing there getting ready to pay, a gentleman comes out from the back with his apron on. He comes over and shakes my hand, and he says, ‘Thank you. My kids are so proud. I tell them, look. He didn’t speak English. Look what he’s doing.’

It’s occurred to me that I get stopped on the street a lot by taxi drivers who’ll lean out of the window and say, “Keep doing it!” Construction workers, people who work in restaurants. And it feels good to me because I think maybe what I’m talking about, in the way that I’m talking about it, is not high-falutin. It’s in the people’s language. And I think that’s a good thing.

Alex Zimmerman contributed reporting.