Principal Gail Lambert had a problem: Cell phone use was out of control.

Not long after taking the helm three years ago of the Brooklyn Academy of Science and the Environment, known as BASE, she was fielding a mountain of complaints about mobile devices. Students were constantly on their phones in the hallways, using them to look up test questions, and shooting videos of school fights.

“One of the huge complaints from the teachers was cell phones,” Lambert said. “In the classroom, [students] would sit with the earbuds in, not focused, not paying attention.”

Nearly five years after New York City’s education department lifted the ban on cell phones, schools across the city, including BASE, are still grappling with an influx of devices and limited guidance about what to do with them.

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in January 2015 he was overturning Michael Bloomberg’s ban on cell phones in schools, saying it was “out of touch with modern parenting.” He gave schools three months to figure out whether they would allow students to store cell phones and other mobile devices in backpacks or at designated school locations.

The policy was intended to address an inequity in the system: The ban mostly affected students at schools with metal detectors, which tend to serve low-income families — like BASE — and it often meant that students at such schools paid at least $1 a day to store their phones at local bodegas and trucks.

The education department does not track individual schools’ cell phone policies, but officials said they worked with schools to craft their policies when the cell phone ban was initially reversed. Teachers union officials, however, say there are dozens of schools that are in the process of rethinking their cell phone policies. At BASE, for instance, staff now collect phones, but the school is looking to purchase lockers to streamline the laborious process.

“While all students are permitted to bring cell phones to school, and we encourage schools to explore the use of mobile applications in their classrooms, we do not mandate or track policy at a school level,” said education department spokesperson Isabelle Boundy.

Finding the right solution

When Lambert joined BASE, students were only supposed to use their cell phones during lunch. It didn’t work.

“It was just a cat-and-mouse game,” Lambert said. Before the school collected cell phones, “If there was a huge fight, they would videotape what was going on.” These videos sometimes spilled onto social media, reverberating inside — and outside — the school.

It’s been a long and winding road for Lambert, working alongside other school staffers and parents, to find a fix.

Last year, the school settled on what seemed like an elegant solution: grey fabric pouches that would allow students to keep phones with them throughout the day, but which could be locked and unlocked by school staff at the beginning and end of the day with a special magnetic device.

But students quickly found YouTube videos with different strategies for getting around the magnetic locks, from ordering specialized magnets online to just smashing them on a table until they opened.

“It was kind of chaotic, because people would pull them apart or rip them or just keep them entirely,” said Abigail Thompson, a senior at BASE who is supportive of the school’s efforts to limit cell phone use.

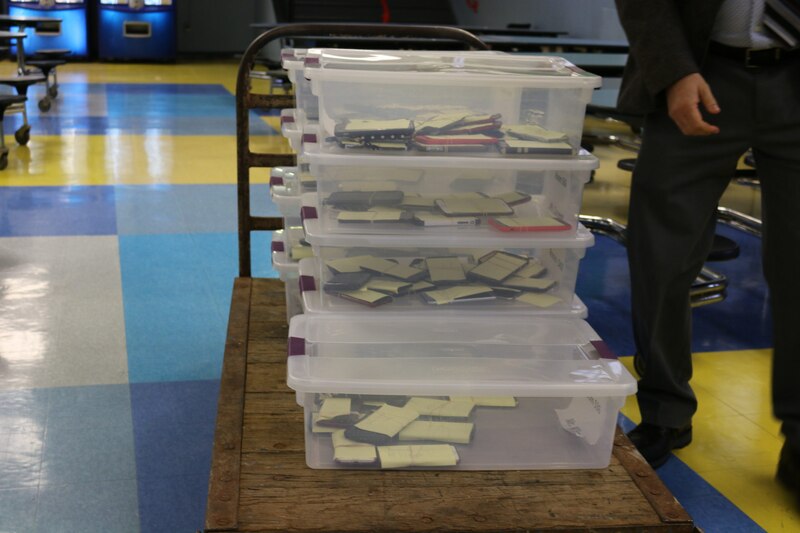

This year, officials abandoned the pouches, which had cost the school $6,000, Lambert said. The school has settled — for now — on a low-tech solution: When students enter the building, they are required to deposit their phones in big plastic bins, affixing their name with a post-it note and a rubber band. The bins are labeled with each last period class, which are given to those respective teachers to return to students at the end of the day.

On a recent morning, students from all four schools that share BASE’s building trickled into the building. BASE students were directed to a table staffed by Eva Hunte, an aide who has worked at the school for 50 years and who students refer to reverently as “grandma.” She is responsible for helping students find the correct bins for their phones, greeting them with smiles and small talk, a process that usually takes a minute or two.

Next, students from all four schools snake their way through an airport-style line to a series of metal detectors. (On a recent morning, one metal detector was down, creating a line that zig zags through the cafeteria.)

Ann Marie, the school’s parent-teacher association president, thought collecting cell phones was having a positive impact in the classroom. “We’re seeing the results — they can focus,” she said.

Lambert said she believes the policy is leading to more students passing their classes and is reducing disciplinary incidents, including suspensions. (City officials have also made it harder for schools to suspend students.)

Now, Lambert said,“Our hallways are extremely peaceful.”

But the current process is time-consuming and labor-intensive, requiring staff members to spend hours each morning collecting phones, including from students who arrive late.

BASE is hoping to purchase cell phone lockers that would allow students to stash their phones more quickly and with less supervision. Locker systems can run thousands of dollars, and school officials are looking for outside funding.

Other schools are in similar situations. The teachers union is working with a handful of them to lobby City Council to fund cell phone lockers, union officials said.

Device-less student concerns

BASE’s cell phone collection process has been popular with many school staffers and some students, though not everyone is on board.

Several students contended the school should only confiscate phones from those who abuse them during the day, and some worried that their phones could be damaged in the school’s care. A few argued that not having their phones could potentially endanger them.

“God forbid, say somebody like a school shooter comes in, we gotta contact our parents, and we can’t contact our parents,” said senior Turrel Tillock. Students, for instance, sent parents frantic texts during the 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Fla. alerting them to the situation.

Other students expressed more day-to-day concerns. Senior Mickayla Harewood claimed her phone was damaged during the collection process, though school officials disputed her account.

“I’m not a very trusting person — an iPhone is expensive,” she said.

(The school will reimburse a student for repairs if the phone is cracked on their watch and said this has only happened once, Lambert noted.)

Another potential wrench in BASE’s cell phone policy: three other high schools that share the building don’t collect phones — and BASE students can sneak in phones by handing them off to a friend at another school and meeting up with them later in a hallway.

School officials estimated that a handful of phones slip through every day. If a student sneaks in a phone, their parent or guardian must come pick it up.

The resulting conversations with parents, who must come to the school to retrieve the phones, can spark conversations about a student’s overall academic performance or other problems. Roughly 70 parents have had to come pick up phones this year, Lambert said.

In one case, she said a mom didn’t realize her son was having significant attendance issues until he smuggled in his phone and the school brought her in. That student with attendance problems, she noted, hasn’t missed a day in weeks following that parent meeting.

Overall, teachers said students are more engaged in classes without phones as a distraction.

“We only have you for 6 hours and 20 minutes,” said BASE science teacher Caren Cleckley, “and we’re trying to prepare you for the next part of your life.”